A marriage of convenience lies behind a campaign to defend Kopassus soldiers on trial for murder in Yogyakarta

Antonius Made Tony Supriatma

One of the routine demonstrations held after the trial closes for the day at Yogyakarta Military Court. Every group takes its turn expressing support for the Kopassus soldiers. A.Harimurti

The killing of four detainees in a civilian prison on 23 March 2013 in Cebongan in Yogyakarta, and the ensuing investigations and trials, have put Kopassus, the Indonesian army’s special forces, back in the spotlight. The attack was carried out by at least 11 Kopassus soldiers (the actual number involved is the subject of conjecture) in revenge for the murder of a plainclothes Kopassus intelligence officer in a bar. The brazen attack on the prison took place after midnight in front of eight prison guards and dozens of prisoners. This murderous raid by special force soldiers on another arm of the state’s security services starkly highlights just how far Indonesia still has to go in reforming this particular part of its military.

Kopassus is Indonesia’s most criticised military unit, with a long history of human rights abuses, from involvement in the killings of hundreds of thousands of Communist party members in 1965-67, to brutalities during the occupation of East Timor, and during the various operations in Aceh and Papua. Under the New Order regime (1966-1998) Kopassus was a loyal defender of the president, with Suharto personally grooming the commanders and senior officers. In the latter years of his rule, it was at the forefront of attempts to suppress opposition, including through the abduction and murder of activists. After Suharto’s resignation, the unit continued to be involved in human rights abuses. In 2001, for example, Kopassus soldiers in Papua province killed the charismatic pro-independence leader, Theys Hiyo Eluay.

Despite its resulting bad reputation for human rights abuses, one of the most remarkable features of the aftermath of the Cebongan killings was an apparently powerful campaign of support for the Kopassus soldiers who were tried for the killings. People watching coverage in the national media, for example, would have seen many demonstrations involving large groups of enthusiastic supporters of the soldiers, suggesting that many people in Yogyakarta supported the killers for their ‘courage’ in trying to clean up crime in the city. But a careful analysis of the campaign in support of Kopassus reveals a great deal of orchestration, and what might prove to be only a temporary alliance of convenience.

The killings and the immediate response

The affair started with a brawl on 19 March 2003 in Hugo’s café which is located on the outskirts of Yogyakarta. The fight was between a plainclothes Kopassus agent, Sergeant Heru Santosa, and a bouncer at the café, Hendrik Benyamin Angel Sahetapi (also known as Decky Ambon). Heru met his death after he was beaten by Decky and a group of Decky’s friends from an ethnically Timorese gang in which he was involved. Police immediately arrested Decky and his buddies. Apparently, the police also knew from the start that the victim was a soldier from a Kopassus unit in the neighbouring town of Kartasura. Accordingly, at noon on Friday 22 March 2013, the police decided to move these detainees from their city headquarters to a local prison.

The attack came anyway, a little over 12 hours later, at around 1.30 am on Saturday 23 March. According to the Army Investigation Team, 11 attackers went to Cebongan prison riding in two cars. They wore vests and face masks, and carried guns and hand grenades. The raid was conducted very efficiently. The attackers pretended to be police officers, knocked on the prison door and within minutes, subdued the guards and forced them to give access to the cell where Decky and his gang members were being held. The attackers forced more than 30 prisoners inside the cell to identify Decky and his group. The executions were then carried out by one man who was later identified as Second Sergeant Ucok Tigor Simbolon.

Predictably, the killings quickly attracted national and international media attention. Although it was not yet clear who the perpetrators were, all indications pointed to the army, especially Kopassus. Not only was the identity of the victims a giveaway, but so too was the fact that the attack was conducted by highly skilled men with commando-style effectiveness. Unsurprisingly, critics quickly alleged that Kopassus soldiers were involved, depicted the attack as a setback to military reform and as evidence of systemic failure to improve the behaviour of soldiers.

The commander of the local military command (Kodam IV Diponegoro), Major General Hadi Saroso, however, vehemently denied the possibility that soldiers might have been involved in the attack. He argued that many people, apart from soldiers, have military-style training. He also contended that the weapons used in the attack did not belong to the military. Within a week, however, the army Chief of Staff, General Pramono Edhie Wibowo (President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s brother-in-law) formed an investigation team. Senior ranks obviously knew this attack could damage the army’s image. The investigation team announced their findings on 4 April, less than two weeks after the killings. The result was straightforward. The attack was conducted by 11 soldiers from Kopassus Group 2, which is located in Kartasura, about 50 kilometres from Yogyakarta. All perpetrators had surrendered themselves to the team on the first day of the investigation. They all pleaded guilty for their wrongdoing. It looked like the case was all but closed.

Cleaning up

Two days after the investigation team announced its findings, Major General Saroso had to pay a high price for his earlier comments, losing his position as Kodam commander. Saroso, an East Timor war veteran (his name is on the ‘Masters of Terror’ list), was transferred to army headquarters in Jakarta without a job. He had occupied the post of commander for only nine months.

On the same day, the police also fired the Yogyakarta police chief, Brigadier General Sabar Raharjo. He was deemed responsible for the transfer of the four prisoners from the regional police headquarters to the Cebongan prison. Many people suspect he had prior information about the attack and decided to transfer the detainees to a civilian prison, avoiding the possibility that the Kopassus soldiers would attack the police office, an act which would have caused more trouble. At the same time, the dismissal of Sabar Raharjo could be depicted as a concession to the military, a counterweight to the firing of his military counterpart.

A total of 12 Kopassus soldiers were indicted, 11 for their direct involvement in the attack, and one for failing to report the attack. All of them were non-commissioned officers. The trial began on 20 June in the Yogyakarta military court. The indictments were categorised into three groups. The first indictment was directed toward three defendants who were the prime suspects in the attack. They were Second Sergeant Ucok Tigor Simbolon, Second Sergeant Sugeng Sumaryanto, and First Corporal Kodik. They were sentenced to imprisonment for 12 years, eight years, and six years respectively and dismissed from military service. The second indictment was directed at five soldiers who supported the attack. Four of them received 21-month jail terms without dismissal from the military. A soldier who acted as the driver for these soldiers was sentenced to just 15 months in prison. The last group of defendants consisted of the three unit commanders of these soldiers. They each got four months and 20 days in prison for failing to report the attacks to higher command.

The support networks mobilise

As soon as the army investigation team announced its findings, the case took a different turn. Social media such as Facebook, Blackberry Messenger, and Twitter, were suddenly abuzz with messages of support for the 11 soldiers. Most of the messages expressed gratitude to them for their courage in ‘eradicating thugs’ from Yogyakarta.

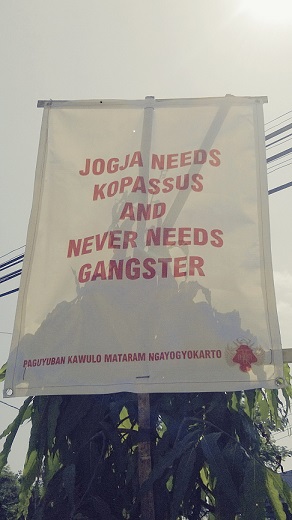

Early in the morning of 7 April, Yogyakartans saw banners, showing support for the Kopassus soldiers, mounted on the main streets of the city. The messages on the banners were similar to those on social media. Slogans included ‘Eradicate Thugs’ (Basmi Preman), ‘I Love Kopassus’, and ‘Terimakasih Kopassus’ (Thank You Kopassus). Several organisations were involved in the installation of the banners. One, called the ‘Face of Yogya’, claimed it mounted 100 banners around the city. Its leader, Irwan Cahya Nugraha Gosong, said they had spent ten million rupiah ($US 800) for the banners, with the money coming from various other groups such as the car and motorcycle clubs, Jogja Otomotif Community and Paguyuban Motor Yogya, as well as FKPPI (The Communication Forum for Sons and Daughters of Retired Military Officers). Banners were mounted not only in the city but also in neighbouring districts like Bantul and Sleman and, later on, as the case developed, in other Central Javanese cities such as Klaten, Solo, Magelang and Semarang.

Also on 7 April, around 200 people staged a rally in the city centre. They carried the photograph of the slain Kopassus soldier and demanded the release of the soldiers involved in the prison attack, saying they were ‘heroes’ ready to sacrifice their lives and careers in order to eradicate criminals. Irwan Cahya Nugraha Gosong was the ‘field coordinator’ (korlap) of the demonstration, with a group that called itself Pemuda Yogya Anti-Premanisme (Yogya Anti-Thuggery Youth) claiming to be the main organiser. The rally was attended by more organisations which included Forum Jogja Rembug, Yogya Artists’ Community, and the Student Executive Body (Badan Eksekutif Mahasiswa or BEM) of Widya Mataram University. A closer look at the activists and organisations involved shows they were all connected to an organisation called Sekber Keistimewaan (see below).

Support for Kopassus and the detained soldiers continued right up to trial. Supporters arranged a visit to Semarang where they were detained and brought gifts such as cakes, coffee, cigarettes, and fruits. They also performed Javanese traditional rituals by burning incense in front of the detention centre. On another occasion, they conducted a street art performance of a trial of these soldiers dressed in Javanese attire. At the time of the trial, supporters packed the military court and often held rallies at the end of the day’s proceedings.

This campaign, with its shift of narrative focus from murder to protection against thuggery or gangsterism (premanisme), caught many in Yogyakarta by surprise. For residents, the shift revived deeper, and darker, memories. In particular it evoked the so-called ‘mysterious killings’ (petrus, or pembunuhan misterius) of 1983. This famous wave of killings of petty criminals, which eventually spread through much of Java, started in this city. They were planned and executed under the direction of the local military commander. The bodies of those targeted were dumped in public spaces. Initially, the government denied that it had a hand in the killings. However, in his biography, President Suharto finally admitted that he had authorised them. Around 10,000 people were killed nationwide. Many Yogyakarta residents still remember vividly the petrus killings. Linking the Cebongan killings to the problem of petty crime meant reminding the city residents of the sense of terror that many of them had experienced 30 years earlier.

At the same time, some active and retired military leaders and political elites in Jakarta stated in chorus that the soldiers acted based on their ‘esprit de corps’. A common viewpoint was that though what they did was wrong, even intolerable, they were to be admired for taking responsibility for their acts and being ready to accept the legal sanctions. Military leaders and political elites depicted this approach as being ‘ksatria’, using a word that has powerful meanings in Javanese culture. Ksatria can be translated as ‘noble’, but it refers to the warrior caste in the traditional wayang stories and can also mean ‘knight’ or even ‘hero’. Even President Yudhoyono jumped in and expressed his support saying that these soldiers were ‘ksatria’ because they were law-abiding soldiers who showed their solidarity to their fellow soldiers.

Three of the convicted Kopassus soldiers (from right to left): Second Sergeant Ucok Tigor Simbolon, Second Sergeant Sugeng Sumaryanto, and First Corporal Kodik. AMT Supriatma

Three of the convicted Kopassus soldiers (from right to left): Second Sergeant Ucok Tigor Simbolon, Second Sergeant Sugeng Sumaryanto, and First Corporal Kodik. AMT Supriatma

The army showed its unity in delivering this message. Almost all army generals conveyed the same message to the public. In order to show his support to his soldiers, the Commander in Chief of Kopassus reportedly slept for a night with his soldiers in their prison cell. Almost all Kopassus generals also showed their support. One retired general, who was actively courting public opinion and mobilisng civilian support, was General Luhut Panjaitan, perhaps not surprising given that the commander of Kopassus Group II is Lieutenant Colonel Maruli Simanjuntak, Luhut Panjaitan’s son-in-law.

Local politics

To understand who was behind the local campaign to defend the Kopassus soldiers, we need to step back and examine some of the background in greater depth. The story gets complicated because of the connections to city politics, including internecine conflicts within the local aristocracy.

The four slain detainees were all members of an organisation that supported KPH Anglingkusumo, the brother and rival of BRMH Ambarkusumo, or Pakualam IX, a local aristocrat who, since 2003, has been the deputy governor of Yogyakarta. The conflict between the two brothers was over succession, specifically about who should become the hereditary ruler of a small duchy called Kadipaten Pakualaman within the greater Sultanate of Yogyakarta. After the death of Pakualam VIII in 1998, his son BRMH Ambarkusumo was appointed as ‘ruler’ of the duchy with the title of Pakualam IX. Since 1950, the Pakualam has normally held the position of deputy governor of the special province of Yogyakarta (the governor is always the Sultan), as one legacy of the pro-Republic role local aristocrats played during the independence revolution, and as one manifestation of Yogyakarta’s status as a ‘special region’ ever since. (The only exception to these general rules is when either of the two officeholders dies. For example, after 1988, when the Sultan died, Pakualam VIII became the acting governor until his death in 1998). Though Pakualam IX was installed in the deputy governor’s office in 2003, in 2012 his brother, KPH Anglingkusumo, challenged the legitimacy of Ambarkusumo’s title. On 15 April in that year he appointed himself as Pakualam IX in a ritual in Kulonprogo. By doing so he also claimed the entitlement to become the deputy governor.

Anglingkusumo’s challenge to his brother’s right to the throne came at a critical time. In 2012 Yogyakarta was experiencing the height of a social movement pressuring the national government to acknowledge the traditional power of the Sultanate and the Pakualaman and to establish the position of the governor and deputy governor as being fully hereditary. The movement was generated by the central government’s plan to make the system of government in Yogyakarta the same as in other regions in Indonesia, where the head of regions are directly elected by the people. Under this plan, the power of the Sultan and the Pakualam would become merely symbolic.

The central government plan caused controversy. Yogyakartans were divided between supporters and opponents. Organisations that supported the current position of the Sultan and the Pakualam eventually merged into a loose joint-secretariat called the ‘Sekretariat Bersama Keistimewaan’ (Joint Secretariat for Special Status), famously known as ‘Sekber Keistimewaan.’ The secretariat, which was established in 2010, did not have a board but was run by a coordinator, with a former student activist, Widihasto Wasana Putra, elected to this position. Because of the looseness of the Sekber’s structure, it is hard to determine how many organisations were affiliated with it. But it was endorsed by around a dozen organisations from a variety of backgrounds.

According to its coordinator, Sekber’s main function was to ‘synergise all the movements in Yogyakarta who want to keep Yogyakarta’s status as special region within the Republic of Indonesia.’ The Sekber had no office, with its meetings usually conducted in the offices of a local publisher, Galang Press. The Sekber militantly defended the Sultan’s position through a variety of demonstrations which generally targeted president Yudhoyono’s national government.

Meanwhile, in order to strengthen his claim to the Pakualam throne, Anglingkusumo had aligned himself with an organisation called Kotikam (Komando Inti Keamanan or the Core Security Command). Kotikam is basically a thug outfit of a type that is common throughout Indonesia. It is led by Ronny Kintoko, the son of a famous former Yogyakarta gangster from the 1980s.

This is where the connection between local politics and the murders comes in. The four slain detainees were not only Kotikam members, they had also all served as personal bodyguards for Anglingkusumo (although most members of Kotikam are Javanese Muslims, these four men were Timorese and Christians). Meanwhile, because the Sultan and the Pakualam have a shared interest in defending the status quo, it is not surprising that they see Anglingkusumo’s faction as a threat. On several occasions before the killings, the supporters of the Sultan and the Pakualam, organised mostly in Sekber Keistimewaan, clashed with Anglingkusumo’s supporters, organised mostly in Kotikam.

As a result of these political circumstances, it is no wonder that the Sekber Keistimewaan became the backbone of support for the Kopassus soldiers and the anti-thuggery campaign. This group – formed to defend the Sultan and the Pakualam and their claims to hereditary rule – have stood behind every action to support Kopassus in Yogyakarta.

Struggling for relevance

The ‘struggle’ to keep the Sultan’s job as governor without electoral processes was won by the Sultan, Sekber Keistimewaan and their allies in September 2012 when the national parliament and government passed a law endorsing Yogyakarta’s special status and maintaining the hereditary principle for appointment of the governor and deputy governor. Ironically, the success also posed a problem for the Sekber. With the passage of the law, the Sekber suddenly lost relevance.

However, it refused to vanish. The Cebongan case gave it the opportunity to reclaim its relevance. Suddenly, it was in a position once more to strut the streets of the city, demonstrating its mobilising power and claim a role as the protector of the security of the citizens.

Making a point. A. Harimurti

Making a point. A. Harimurti

There are two other reasons why Sekber has supported the Kopassus soldiers. First, the case has helped it to maintain unity among its member organisations, and even to broaden its appeal. Sekber is really an umbrella group consisting of a hotchpotch of organisations with very diverse backgrounds. Even so, in term of religious worldview, the Sekber members mostly represent the kejawen or abangan worldview, whose adherence to Islam is nominal and who mix their Muslim faith with various Javanese folk traditions and beliefs. This loyalty to tradition is also what binds them to defend the aristocracy. Interestingly, some of the most prominent leaders of the Sekber are Javanese Catholics and Protestants. This background has created uncomfortable relations between Sekber and more strictly Islamic groups.

By choosing to ally itself to the Kopassus, Sekber was able to pull in Muslim groups under its umbrella. Muslim organisations such as Barisan Serbaguna Ansor (Banser), the paramilitary group affiliated with the traditionalist organisation, Nahdlatul Ulama, and Komandan Kesiapsiagaan Angkatan Muda (KOKAM) Pemuda Muhammadiyah, a similar group with affiliations to the major modernist organisation, Muhammadiyah, were among the strongest participants in the movement to support the Kopassus soldiers. These organisations also have a long history of cooperating with the Special Forces and the military, dating back to the killings of the Communists in 1965-66 and during the New Order.

The second reason why Sekber leaders defended Kopassus was that they could benefit from the protection that such a powerful institution at the national level could offer them. After their victory in the prolonged fight for the status of Yogyakarta some Sekber activists have begun to pursue other political and economic interests. For instance, some have won various construction contracts and business concessions from the government. Some are pursuing or planning to pursue public office. Like other local leaders on the make in contemporary Indonesia, they know they will be able to prosper more quickly if they can build links with backers from a powerful national institution.

A mutually beneficial arrangement

The Cebongan case drew Kopassus and Sekber together into a marriage of convenience. Kopassus has used Sekber and its affiliates to create an image of popular support for its soldiers. By demonstrating such civilian support, Kopassus officers hope that can burnish their unit’s long-tarnished image. The engineered demonstrations of ‘dukungan rakyat’ (support from the people), have also allowed them to revive the old mantra that the Indonesian military is a ‘people’s army.’

The Sekber leaders, on the other hand, have used the Cebongan case to revive their organisation’s relevance in Yogyakarta’s local politics and to broaden its network to include new actors, such as Muslim organisations. It has also allowed them to gain the protection of a major wing of the state’s security.

Will this mutual advantage last? It is hard to predict. In the ever-changing world that is contemporary Indonesian politics, alliances of convenience can rise and fall with startling rapidity. As one Sekber leader told me in an interview, ‘Now we have the same interest with the Kopassus, which is to eradicate preman. Next time, we may have to confront the Kopassus in another case. Nothing is permanent here.’ People who see in the Cebongan case evidence of a groundswell of popular support for the military and its role in Indonesian society should take careful note.

Antonius Made Tony Supriatma (supriatma@gmail.com) works for a non-profit news organisation, JoyoNews, in New York.