Barbara Hatley

In his introduction to Talking North, Paul Thomas suggests that the study of Indonesian language and culture in Australia might be described as a ‘national project’, a pathway to a deeper understanding and engagement with our nearest Asian neighbour. The contributors to this book, as a group of people deeply involved in and committed to this project, reflect on its history and current development, and relate their own experiences, first as curious students then as passionate teachers of Indonesian.

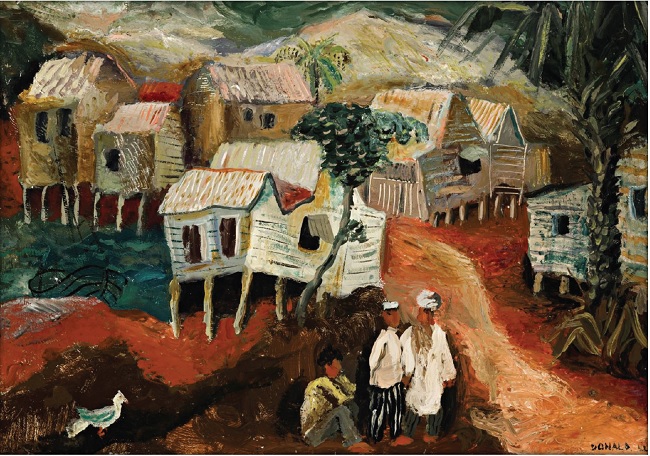

The first part of the book focuses on the changing fortunes of Indonesian language teaching programs and the political, economic forces and government policies which have shaped them. Paul’s two chapters provide a broad historical context for these processes. His first chapter describes how Malay language was used in early interactions between the indigenous people of northern Australia and Indonesian traders, as a lingua franca in the mixed-race settlements of the north in 19th century, then promoted to facilitate trade with the Indonesian archipelago in the 1930s and for military purposes during World War II.

The second chapter takes the story forward into the 1950s, when Australia was attempting to work out its relationship with newly-independent Indonesia. Paul enlivens the narrative with some intriguing anecdotes about important historical figures involved in this activity, such as Prime Minister Menzies, writing a speech in his bathtub, then delivering it in Bahasa Indonesia on his state visit to Indonesia, despite being declared ‘language deaf’ by the Indonesian-speaking Australian diplomat called in to coach him for the task. A key focus of Paul’s account are efforts by Australian governments to promote the study of Indonesian, largely for political and economic purposes, by encouraging and helping to fund the establishment of Indonesian language programs in universities and schools.

The other chapters in the first part of the book report on the ‘roller coaster’ history, the times of expanding growth then plummeting decline of these courses themselves.

Firdaus’ contribution discusses the political factors impacting on Indonesian language teaching; ‘political’ in the sense of international political developments, national government programs and internal university politics. She reports on the dramatic rise in numbers of students studying Indonesian in schools with the implementation in the mid-1990s of the government-funded NALSAS (National Asian Languages and Studies and Schools) strategy, then the sharp decline and, after a change in government, its cancellation. She suggests that academics need to work with government and university decision-makers to try to ensure the survival of Indonesian language programs.

David Hill’s chapter focuses specifically on developments in Indonesian language teaching since 2000, both in Australia and ‘in country’ courses in Indonesia. He cites statistics on student enrolments in Indonesian courses in different Australian universities which present a shared picture of steep, ongoing decline. A ‘string of crises’, ‘a perfect storm’ of catastrophes involving Indonesia (the East Timor debacle, the 2002 and 2005 Bali bombings, the Bali Nine drug trials) had drastically discouraged interest in learning Indonesian language while the government paid little attention to supporting Indonesian teaching programs. Meanwhile, the situation of in-country programs appears considerably brighter. Both Labour and Liberal governments have introduced programs funding Australian students to study Asian Languages in Asian universities (Asia Bound and the New Colombo Plan). ACICIS (Australian Consortium of In-Country Language Study) based at Murdoch University and other in-country Indonesian language programs, have benefited substantially as a result; their enrolment figures show continuous growth from 2010-2019. Yet unless the programs on Australian campuses receive significant government and university support David sees ‘Indonesian expiring in ever more universities over the coming decades’.

Of the other chapters in Part One, Julia Read and David Reeve’s contribution focuses on teaching methodologies. It documents the changing approaches to university Indonesian language teaching employed over the decades, identifying their strengths and weaknesses, with special attention to materials developed by the TIFL (Teaching Indonesian as a Foreign Language) project. (Novi Jenar’s discussion in Part Two of the teaching of Indonesian grammar and the need to include examples of colloquial spoken Indonesian would also seem to belong better in this section.)

Charles Coppel’s chapter, describing the history of the teaching of Indonesian language at the University of Melbourne as a ‘roller coaster ride’, identifies many features also experienced by language programs at other Australian universities. These include changing government education policies and funding levels, the ‘ups and downs of the relationship between Australia and Indonesia’, and shifting university structures and priorities. At the same time the Melbourne program faced additional problems due its small size and vulnerable position, and many changes and uncertainties of staffing. Interestingly, since the introduction in 2008 of a new degree structure requiring students to undertake ‘breadth’ units which can include languages, the Melbourne program has seen significant growth in student numbers in contrast to the national picture of continuing decline.

These chapters provide much valuable information about the history of Indonesian language programs in Australia. Yet the overall picture they give is one of loss and decline. Part One ends on a deeply troubling note with David Hill’s observation ‘If the evidence from the past 15 years is any indication, the language of our nearest neighbour faces a bleak and uncertain future in Australian universities.’

But turning to Part Two, consisting of stories of the personal experiences of the writers, the mood lightens.

A personal approach

Here are accounts of eye-opening, often fortuitous encounters with Indonesian language and culture which led on to a richly fulfilling career. Jan Lingard writes of enrolling in 1969 in an adult education course called ‘Our Northern Neighbours’, partly to find out who those neighbours might be, discovering ‘such a fascinating and different culture was here, right on our doorstep’, then going on to learn Indonesian language, study Indonesian and Asian Civilisations at ANU and embark on a career as a university Indonesian language tutor and lecturer.

Ron Witton similarly recounts the story of an accidental encounter at Sydney University in 1962, with an Indonesian student who began to teach him a few words of Indonesian. Finding out that the University of Sydney actually taught this language he found much easier to speak than the French he’d studied for five years at high school, Ron ‘went with a sense of wonder to the Department of Indonesian and Malay’ and enrolled. After completing a year of study, he took off to ‘see the fabulous country I had heard so much about’ and at the end of his third year travelled again to Indonesia, where he heard President Sukarno ‘give one of his electrifying speeches… and even managed to have breakfast with him at the Jakarta Presidential Palace.’ (Wow!) Like many of his classmates Ron went on to become a teacher of Indonesian. His glowing account of his studies of Indonesian at Sydney University highlights particularly the inspirational teaching of one of his lecturers, Pak Emanuels.

Stuart Robson, who also studied Indonesian at the University of Sydney in the 1960s, provides some wryly amusing profiles of his lecturers― of Dr F. H. Naerssen, for example, ‘rambling on about ‘those palmy days of Majapahit’, smoking four cigarettes every lecture and taking a half hour nap each day after lunch. Yet such idiosyncratic behaviours clearly didn’t lessen the fascination of Indonesia for Stuart and his fellow students. The honours group in 1962 consisted of Stuart, Peter Worsley, Harry Aveling and George Miller, all of whom would go on to contribute significantly to the field of Indonesian Studies. And in 1964 and 1965 respectively, Peter and Stuart set out for further studies in ‘the fabled city of Leiden’, the ‘Mecca’ of Indonesian Studies at that time.

In his insightful discussion of changing conceptions and ways of teaching Indonesian literature, Keith Foulcher points out that the way literature was approached during the time of his study was actually quite inappropriate for undergraduate students of Indonesian in Australian universities. This universalist model, focusing on the aesthetic qualities of literary works, with minimal attention to their social context, denied students the opportunity to read them as a way into understanding Indonesian society and culture. Yet at the same time modern Indonesian literature as a new, evolving field ‘held out an invitation to become involved in something completely new.... a field of study just waiting to be explored’. Keith reports that students of modern Indonesian literature were welcomed as friends and colleagues by both Indonesian writers and the international scholars who had written about their work. ‘For a 20-year-old with a love of literature and the study of languages’ he observes ‘what could be a better prospect and a more exciting way to embark on an academic career?’

Some of the stories in Part Two focus particularly on the writers’ experiences of teaching and their interactions and collaborations with other teachers. Lindy Norris describes the excitement of her work in teacher education at Murdoch University in the early 1990s when there was ‘a steady stream of people who saw their futures in Indonesian language classrooms’. She writes of ‘amazing’ teachers of Indonesian with ‘a passion for what they were doing and a desire to ‘infect’ their students with the same interest in Indonesia.’ Lesley Harbon relates learning Indonesian language with such accomplished language teachers that she was inspired to ‘learn the craft of Indonesian teaching myself’. She describes her interactions with a ‘web’ of Indonesian language educators across Australia and beyond, collaborating with many of them in the production of an Indonesian language teaching resource, Pelangi (Rainbow) magazine. My own brief contribution to the volume focuses on the Indonesian language plays I staged with students of Indonesian at Monash in the 1980s and early 1990s. For me, this was particularly rewarding and enjoyable ‘teaching,’ and for the students a great bonding experience and way of enriching their language skills and cultural understanding.

Several of the writers lament the fact that students of today will not have experiences of Indonesian language learning and teaching similar to their own. Yet their stories convey a sense of the excitement of earlier times when interest in Indonesia was growing, Indonesian programs were expanding and new opportunities seemed to be constantly opening up; a ‘golden age’ to be remembered and celebrated.

But where to go from here? What prospects for the survival of Indonesian language programs, and the wider project of understanding and engaging with Indonesia?

While the contributors have no answers to these questions they point to some positive developments – inter-university collaborations in language teaching, new online learning technologies, and in particular the expanding growth and popularity of in-country courses. David Hill writes of the ‘direct personal – and often profound – experience of living in Indonesian society… and deep commitment to bilateral understanding’ as well as Indonesian language skills of the thousands of graduates of these programs who are now moving into influential positions in Australian society, government and business. These people may well have the opportunity to extend understanding of Indonesia and promote Indonesian-Australian relations in exciting new ways.

In addition to formal language teaching courses, other important new initiatives are also assisting young Australians to learn about and actively engage with Indonesia. The ReelOzInd! Australia Indonesia Short Film Festival, for example, provides the opportunity for young filmmakers from Australia and Indonesia to participate in a short film competition, and screen their works widely in both countries, along with Q&A sessions introducing the film makers to local audiences. The Australian-Indonesian Youth Association, AIYA, described on its website is a ‘non‐government, youth-led organisation which aims to better connect young Indonesians and Australians to each other and to Australia-Indonesia related opportunities’ has branches in each state of Australia and several regions in Indonesia. It holds events such as talks by guest speakers, debates, movie nights (even a rugby competition in Yogyakarta!), organises the National Australia-Indonesia Language Awards, an annual competition aimed at stimulating interest in Indonesian language learning, and publishes a weekly e-newsletter with reports of these activities.

Talking North provides a valuable and comprehensive account of the history so far of Indonesian language teaching and learning in Australia. An exciting next step would be a new study, taking the narrative forward, describing the impact of these new developments and giving voice to those involved. Another chapter in the story, just waiting to be told.

Barbara Hatley is an Emeritus Professor of Indonesian at the University of Tasmania. Her major research interests are Indonesian theatre, literature and gender studies. She is one of the contributors to Talking North.