The vibrant force of As’adiyah is countering Islamic extremism and safeguarding ethnic and cultural identity

Mark Woodward

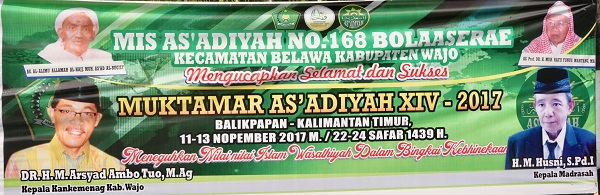

In November 2017, around 1300 Indonesians of Buginese ethnicity gathered in Balikpapan. Many had come from Sulawesi by ship. Others were from Java and Sumatra as well as elsewhere in Eastern Indonesia. All of them were excited. They were there to attend the national convention of the South Sulawesi based, ethnically Buginese, As’adiyah movement: one of Indonesia’s most vibrant forces in efforts to counter Islamic extremism.

In recent decades, the growing influence of transnational Salafi movements has been a matter of great concern in Indonesia. Salafi movements insist on literal interpretations of Islamic texts and argue that cultural traditions other than those of Saudi Wahhabis are not authentically Muslim. Such claims threaten to disrupt the delicate balance of inter-religious and inter-cultural tolerance on which many Indonesians have come to depend. Salafi movements are also frequently blamed for the recent growth in violent jihadist sensibilities within Indonesia’s Muslim population. In response, many Islamic organisations have developed ideologies and symbols with which they might counter Salafist influences. Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), Indonesia’s largest Islamic organisation, now promotes what it calls ‘Islam of the Archipelago’, emphasising traditional Sufi religious teachings and a strong commitment to Javanese culture. By contrast, Muhammadiyah, the nation’s second-largest Islamic organisation, places universal human values and global engagement at the heart of its ‘Cosmopolitan Islam’.

‘Islam of the Archipelago’ and ‘Cosmopolitan Islam’ have attracted much attention in the Indonesian and international press. But As’adiyah members feel that neither vision is quite right for Indonesia’s Buginese population, over six million in number. They used their 2017 convention to explore, articulate and strengthen an alternative vision – Islam Wasathiyah, or ‘Middle-Path Islam’ – that might counter the influence of extremism within this particular ethnic group.

A traditionalist movement

As’adiyah is a traditionalist Muslim movement founded in Wajo, South Sulawesi, by Anre Gurutta Haji Muhammad As’ad in 1930. Like NU and other traditionalist movements, it is deeply rooted in the classical Arabic textual tradition including works on theology, Sufi mysticism and Islamic law (its texts are called ‘Kitab Kuning’ [Yellow Books] because of the colour of the paper they are printed on). It values local cultural traditions. Indeed, it was founded as a counterpoint to the exclusivist sensibilities that can be seen in much contemporary Salafism.

Muhammad As’ad was born in Mecca in 1907. His parents were from prominent families of Buginese ulama (Islamic scholars). He was a child prodigy, memorising the Qur’an by the time he was 14. A year later he was authorised to lead evening prayers during Ramadan at the Grand Mosque. In 1927, at the age of 20, he was granted permission to issue fatwa (legal opinions). Despite having been exposed to the writings of the influential Egyptian modernist Muhammad Abduh, As’ad did not accept the modernist view that the Qur’an and hadith (traditions concerning the Prophet Mohammad) are the only valid sources of Islamic law and knowledge. He valued centuries-old traditions of Muslim theological and legal scholarship and jurisprudence, following the Shafite school in ritual and legal matters. Like most Mecca trained ulama of his time, As’ad was also a Sufi. Nevertheless, and remaining true to his Meccan origins, As’ad was still a little Arabo-centric, teaching that Friday sermons must be delivered in Arabic. The As’adiyah movement has since abandoned this practice. Friday sermons are now delivered in Buginese or, less frequently, in Indonesian.

Like many traditional Indonesian ulama, As’ad found the Wahhabi Saudi kingdom to be unpalatable because of its exclusivist policies than banned most traditionalist teachings. He moved to his homeland of Sulawesi in 1928. His purpose was to promote traditionalist orthodoxy and to ‘purify’ Buginese Islam of what he believed to be deviant teachings, polytheism, and prohibited forms of religious innovation. In this respect, his religious agenda resembled that of Ahmad Dahlan, Muhammadiyah’s modernist founder. Unlike Ahmad Dahlan, however, he did not advocate an anti-Sufi agenda, but rather the Sufi-oriented Meccan orthodoxy as it was before the imposition of Wahhabism in 1926. As’adiyah continues to defend the Islamic authenticity of devotional practices that Muhammadiyah and other modernists consider unacceptable, including prayers for the dead and pilgrimages to holy graves. A senior As’adiyah leader described As‘ad’s mission as religious purification, ‘but purification à la NU, not à la Muhammadiyah’. He also explained that in the 1920s Buginese Islam was ‘not much more that the Confession of Faith’ and that As’ad had been determined to change that. Despite religious similarities, As’adiyah is not formally affiliated with NU, but many members and followers are.

As’ad founded Madrasatul Arabiatul Islamiah (School for Arabic and Islamic Studies) in Wajo in 1930. It was renamed Pondok Pesantren As’adiyah after his death. His students founded other pesantren (traditional Islamic boarding schools) in South Sulawesi and in Buginese communities throughout Indonesia. Today there are more than 1200 As’adiyah schools ranging from kindergartens to Islamic colleges. The movement operates pesantren in Sulawesi, Maluku, Kalimantan, Java and Sumatra. Almost all the students are Buginese. Buginese and Arabic are the primary languages of instruction. There are now many hundreds of thousands of alumni.

As’ad’s face adorns a banner welcoming delegates to the Balikpapan convention: Mark Woodward

A vision for education

As’adiyah’s attitude to education is just one way in which it counters exclusivist ideologies with a more cosmopolitan approach. Its schools teach a combination of religious and secular subjects. As’adiyah also stresses the importance of higher education, encouraging students to pursue undergraduate and advanced degrees in Indonesia and abroad. This is in keeping with broader patterns of cultural change. Higher education is now so important in contemporary Buginese society that it has supplanted hereditary aristocratic titles as a source of social status. For example, Buginese tradition requires marriage payments from the groom’s family to the bride’s; young women from highly educated families and those who are themselves highly educated now command such high ‘brideprices’ that, as one As’adiyah leader put it, ‘only very wealthy men can afford to marry them’.

As’adiyah’s commitment to education is evident in its senior leadership. Most members of the central leadership board have PhDs, and several hold prominent positions at Indonesian universities. One member, Dr Kamaruddin Amin, even serves as the director-general of Islamic education at the Ministry of Religion. Several of As’adiyah’s leadership obtained their doctorates in subjects such as Islamic Studies and Near Eastern Studies from universities in Europe and the United States. This is significant. Some Indonesian Muslims, especially Salafis, question the religious propriety of studying Islam in the West. Yet, at the Balikpapan convention, Kamaruddin Amin challenged this view . He stressed that it is important to study with the most learned teachers wherever they may be. He said that there are prominent ulama in many places including Europe and North America as well as in the Middle East and Indonesia. He cited the example of the Pakistani-American scholar Fazlur Rahman, who taught at the University of Chicago. He also stated that Indonesia should aspire to become a global centre for Muslim education and to attract international students in same way that al-Azhar University in Cairo and the Islamic University in Saudi Arabia do. In this way, the cosmopolitan sensibilities of As’adiyah not only open up multiple educational pathways for individual Muslims, but new possibilities for Indonesia’s place in the world.

The middle path

The As’adiyah movement has a long history of opposing violent extremism. In the 1950s it strenuously opposed the Darul Islam (Islamic State) movement that was active in South Sulawesi. Today it strongly opposes the Sulawesi based Wadah Islamiyah, the national Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia and other Salafi movements. It is also progressive on gender issues in ways that Salafis are not. Women were active participants in the Balikpapan convention to an even greater extent than they are in similar Muhammadiyah and NU gatherings.

Such activities are grounded in As’adiyah’s core commitment to Islam Wasathiyah (Middle-Path Islam). Many participants at the convention stressed the importance of wasathiyah thinking as a strategy for combating violent extremism. A student from an As’adiyah pesantren felt religious extremism and intolerance were the most important problems facing Indonesia. ‘Studying Kitab Kuning is not enough,’ he argued. ‘We must work together to promote unity and tolerance. Supporting Pancasila (Indonesia’s national ideology, which mentions devotion to God, but not Islam) is the way to do this.’ This combination of nationalism, pluralism and devotion to traditional Islamic teachings is genuinely a ‘middle path’. It sets As’adiyah apart from both secularists and extremist Muslims who call for implementing syariah at national and local levels. It also reaffirms the religious and political rights of non-Muslims that extremists continue to challenge. Public support for these views is especially important because of the role that ethnicity and sectarianism played in the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election and concern that they will figure significantly in the 2019 presidential contest.

Gender inclusive deliberations on religious issues: Mark Woodward

Ethnic and cultural diversity

Ethnic diversity and Muslim unity were also persistent themes at the convention. Speakers and participants stressed the fact that there are hundreds of ethnic groups in Indonesia and that Islam and shared humanity make important contributions to Indonesian national unity. There was, however, only qualified support for NU’s Islam of the Archipelago program. Several participants stated that Islamic culture is useful for countering extremism but that Islam of the Archipelago was ‘too Javanese’ because of its emphasis on Javanese Muslim saints and the shadow play tradition, itself based on Javanese versions of Hindu epics. Shadow plays are performed in Javanese, which few Buginese understand. And while Buginese are as devoted to saints as traditional Javanese Muslims, they have their own. ‘[Islam of the Archipelago] is not for us,’ one participant stated. ‘We are Buginese.’ Another explained that what was needed was ‘not cultural dakwah (propagation of Islam) but rather multi-cultural dakwah.

Such attitudes reflect the growing emphasis on local cultures associated with Indonesia’s democratisation, a counterpoint to the Javanisation of Indonesia that took place under the New Order. When asked about distinctively Buginese features of As’adiyah, many delegates mentioned language and the fact that it is a focus point for Buginese identity among the diaspora. By formulating a distinct middle-path Islam as a counterpoint to the efforts of NU and Muhammadiyah, As’adiyah is allowing Buginese Muslims to play an active role in the fight against extremism while safeguarding their ethnic and cultural identity.

There is a growing consensus among Indonesian Muslims that actively promoting the study of traditional Islam and local cultures are important strategies for combating religious extremism. Most extremists regard traditional Muslim teachings as heresy and local cultural performance traditions as sinful and ‘not Islamic’. Promoting their Islamic authenticity strikes at the heart of extremist teachings. The endeavours of Javanese Muslims, who constitute nearly sixty per cent of the Indonesian population, are important, but should not overshadow those of individuals and organisations of other ethnic backgrounds. Organisations such as As’adiyah are of critical importance outside of Java and for the forty per cent of Indonesians who are not Javanese. And this importance was keenly felt by the delegates of the As’adiyah national convention. As they left Balikpapan to return to their places of origin, they did so with a renewed commitment to educational cosmopolitanism, cultural diversity, and ‘middle-path Islam’ that updates As’ad’s rejection of Wahhabism for the challenges of the present day.

Mark Woodward (mark.woodward@asu.edu) is associate professor of Religious Studies and affiliated to the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict at Arizona State University.