Decolonising knowledge

The miners, the orderers and the criminals have generations. What about us?

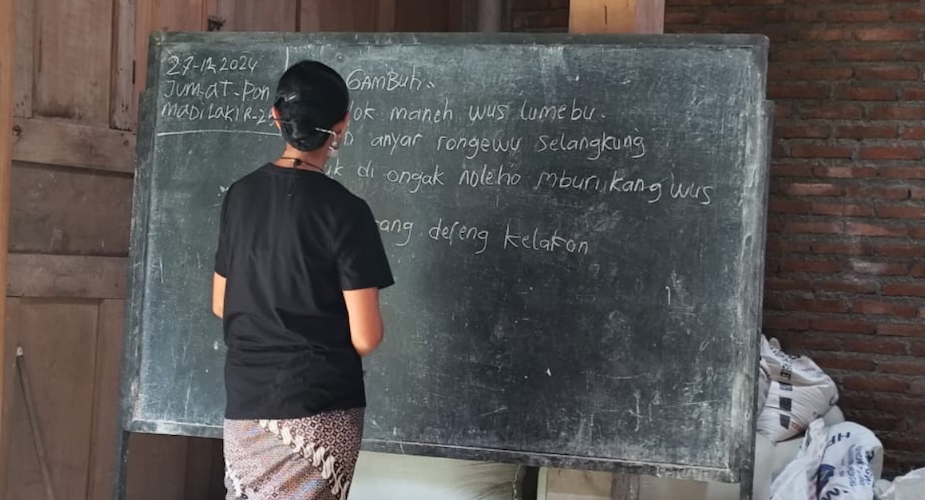

That's the question that keeps running through the mind of Gunarti, a female farmer from Sukolilo, Pati, Central Java. She was born on a special date—the same as R.A. Kartini's birthday, 21 April. Just like the national hero Kartini (1879-1904), who fought for children's education, especially for girls, Gunarti believes in the importance of knowledge. In 1993, she opened a learning space for the children of Sedulur Sikep, her community, around the Kendeng Mountains. Every Friday, she spreads out a mat in the living room of her house, where children and teenagers learn about the meaning of life in two languages and two scripts: Indonesian and Javanese, Latin script and Javanese script.

As the mother of three children, Gunarti was raised in the teachings of Surontiko Samin (1859-1914) . Also known as Samin Surosentiko or Ki Samin, he was a central figure and source of knowledge for the Sedulur Sikep community. Mbah Samin is renowned for his refusal to submit to the capitalist Netherlands East Indies government, which branded him a rebel. He was arrested and exiled to Sawahlunto in West Sumatra, where he ultimately died. Even though Gunarti was born more than fifty years after Mbah Samin's death, she continues to uphold his teachings as a guiding light. She inherited his values and actively embodies them: living in harmony with nature, practicing honesty, rejecting violence, and standing firm when truth is undermined.

Gunarti and her family reside at the base of the Kendeng Mountains in Sukolilo, Pati, Central Java. This region is renowned for its karst landscape, a natural formation of limestone that acts like a giant sponge, storing water and playing a crucial role in ensuring water availability. Even during droughts, water continues to flow from the karst hillsides. Therefore, Kendeng serves not only as a home for humans but also as a vital life support system for all forms of life.

Cement

The tranquility in the villages began to unravel when news of the proposed cement factory construction circulated. Gunarti observed firsthand how the presence of the quarry and the factory sparked unrest among the residents from the beginning. Tensions arose among neighbours and even within families, between those who opposed and supported the project . Amidst these conflicts, Gunarti stood resolutely alongside the other Kendeng women, united in their rejection of the plan to devastate their home region.

When plans for a cement factory began circulating in Pati in 2006, the Sedulur Sikep sought to uncover the truth behind these plans. They gathered in the Sonokeling forest, met with local government officials, and received confirmation of the troubling news: the PT Semen Gresik cement factory would be constructed in Sukolilo. The Sikep community realised that this plan posed a significant threat to the Kendeng Mountains and surroundings, particularly Sukolilo, which serves as a food granary in Pati Regency. The dismantling of the karst would lead the rice fields to dry up. In fact, over 10 per cent of the rice fields in Pati Regency are located in Sukolilo, spanning sixteen villages with a total land area of 13,754 hectares (Pati Regency Statistics Agency 2020). Traveling through the Sukolilo sub-district, from Gunarti's house in Sukolilo Village to Kaliyoso, one can observe extensive stretches of rice fields. The water that nourishes these fields comes from nearby rivers and the water sources of the Simbar and Wareh caves.

In 2008, as the Kendeng karst mountain region faced a serious threat of demolition, the farming-dependent Sedulur Sikep community took a stand. They became the primary force behind the movement opposing the cement factory plan. For years, they traveled a challenging road, voicing their objections, pursuing legal avenues, and fostering solidarity among community members. In 2010, their efforts paid off when they successfully drove PT Semen Gresik out.

Shortly after, PT Sahabat Mulia Sakti (SMS), a subsidiary of PT Indocement Tunggal Prakarsa, turned its attention to the neighbouring areas of Kayen and Tambakromo. Residents once again took action, suing over the issuance of factory and mining permits. On November 17, 2015, they achieved a victory at the Semarang State Administrative Court (PTUN).

However, the government of Pati Regency and the company, PT SMS, were not easily deterred and appealed the decision to the Surabaya State Administrative High Court (PTTUN). Meanwhile, in 2012, PT Semen Gresik, which later rebranded itself as PT Semen Indonesia, obtained a permit for the Tegaldowo Village area in Rembang Regency, where construction of a cement factory began in 2014.

Women

While following the cement case journey, Gunarti realised that women often lack the opportunity to participate in crucial meetings where the negative impacts of mines and cement factories were discussed. She was also concerned that women were not receiving sufficient information about the particular threats that they faced. Their position could become quite precarious if approached by the opposing side regarding the sale of their land. Gunarti believed that women can accomplish far greater things when provided information and opportunities for reflection, sharing, and discussion. She has put forward this argument at various meetings.

Since the end of 2007, Gunarti has visited approximately twelve villages that the cement factory will impact. However, as a woman and a mother, her spare time is limited—only the afternoons or evenings. Even then, to accomplish her visits at night she often had to borrow a motorcycle or ask for a ride if the location is quite far. For the closer villages, Gunarti chose to use her old bicycle (ontel) alone. Gunarti's efforts strengthened the position of the Sedulur Sikep and nearby residents who opposed the cement factory.

The strength of women began to emerge after the formation of the Simbar Wareh women's group, which holds regular meetings every two weeks. Simbar Cave and Wareh Cave, two important water sources around Sukolilo, inspired the group's name. Simbar Wareh was the first women's organisation to openly reject the cement factory in Pati.

In 2008, cement resisters took the issue to the courts. In 2010, the Supreme Court ruled that PT Semen Gresik and the Pati regency government had violated the spatial plan. The court recognised that the spatial plan at the time designated the area for agricultural and tourism areas, not for the cement industry.

However, the struggle is not yet over. Following her success in stopping PT Semen Gresik at Sukolilo, Gunarti encountered a new challenge as PT SMS, a subsidiary of Indocement, began to encroach on neighbouring areas. Gunarti once again mobilised Simbar Wareh to inform the residents of Kayen and Tambakromo, the two subdistricts that PT SMS would affect. As she had done previously, Gunarti engaged directly with women across various villages, visiting from house to house and attending religious gatherings. In total, she visited about fourteen villages.

This time, however, the pressure from the authorities was more intense. Neighbours' remarks, sometimes delivered with a sarcastic undertone and even directed towards Gunarti's husband Kang Koh, also reflected social pressure. Her husband told her people had said to him: "Your wife will be stolen by another man later, Kang."

Their house was placed under surveillance. "[Someone] passed by several times in front of the house, [our house] was photographed, and then [the person] left," she stated. Gunarti and her family gradually became accustomed to these intimidation tactics.

Gunarti believes that this negative perception can be effectively countered. "Words are weapons," she remarked. For her, shaping others' perceptions is a skill that must be continually refined in the struggle, including the way we engage nature as an ally. Gunarti contends that nature is not merely an inanimate object but a living entity that should be allied with or even fought alongside.

Children

Gunarti does not merely engage with her community in the streets; she has also sown the seeds of change within her own living room. Since 1993, she has established a traditional school for the children of the Sedulur Sikep community, aiming to instil in them a sense of struggle and a commitment to environmental preservation. A significant motivating factor for her in this effort was a profound sense of sadness and concern, coupled with a determination to advocate for the presence of Sedulur Sikep in greater society. Her sadness intensified when a few of her nephews and nieces confided in her about experiencing peer harassment. "They were mocked... for not going to school," Gunarti recalled.

In response to this concern, Gunarti took the initiative to start a small class in her living room. Initially, only four children attended every Friday evening, including her own two children, Heny and Niken. Classes commenced after sunset prayers (Maghrib) and concluded after evening prayers (Isha). The children learned to read and write, but, more importantly, they gained valuable insights into the daily conduct expected of them as members of the Sedulur Sikep community. She puts the message in the form of a poem:

Wajibe nom-noman iku

Anampeni katehe pitutur

Kanggo muntur

Yo Katoto katiti

Katitio lelakonipun

Lelako ingknng utama

Meaning: Young people are required to accept advice. Once received, this advice should be studied, organised, and acted upon. At the same time, parents have the responsibility to impart this advice.

Gunarti's class operates without a written curriculum; all the material and methods reside in her mind. If we refer to Paulo Freire's book Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), it becomes clear that Gunarti's approach aligns closely with the essence of liberating education for the oppressed. She has revitalised the role of education as a means of raising awareness about various forms of oppression, particularly the experiences of the children at Sedulur Sikep. This learning method emphasises dialogue rather than rote memory, which is commonly employed. Children are encouraged to learn from their life experiences and the surrounding environment, which often does not adhere to the teachings of Sedulur Sikep, while also acquiring knowledge essential for community life. This involves educating them about the local environment in which they reside and are situated.

Gunarti's classes also bring to life the spirit we know today, the decolonisation of knowledge, where she used the Javanese language and script in her teaching, including traditional songs, or tembang. Learning is done by singing without musical accompaniment, using Javanese and Kawi, which is often called macapat. Together with her students, Gunarti has written dozens of songs. She showed a rectangular book with a cover that was starting to peel, which she had been using to write the songs, both in Javanese and Latin script. Children are invited to understand the values of the Sedulur Sikep practice through ancestral language and tones, such as Dandang Gulo and Pangkur.

This school has proven quite effective in fostering the self-confidence of the Sedulur Sikep children to live among their peers. One piece of advice that Gunarti always repeats to her students was 'Ojo gumuman, ojo kemiren', which means "don't be easily impressed, and don't be envious." This advice served as a reminder to resist the allure of modernity.

How many students have studied at this school since its establishment in 1993? 'Probably around a hundred, mostly from two districts: Pati and Kudus'. 'Some of the students have parents who [once] studied here, and now their children are also studying here', said Gunarti. For her dedication to the field of informal education, she was awarded a certificate of appreciation by the Organisation of Solidarity Action for the Era of the Advanced Indonesia Cabinet (OASE) during the 2023 Kartini Day celebration. Iriana, the wife of President Joko Widodo, and Wury, the wife of Vice President Ma'ruf Amin, personally signed the award.

Nature

Gunarti rejects the notion that the economy serves as the sole foundation of well-being. She views such a perspective as a form of oppression. She argues that clothing, food, and human morality should be regarded as equally important foundations. Addressing the needs for clothing and food is intrinsically linked to the protection of people's lands, while morality encompasses the respect for diverse beliefs and lifestyles. Gunarti's voice responds to the intersection of state power, religion, ethnicity, gender, education, and language, which create various layers of oppression.

During the New Order era, her grandparents, along with Gunarti herself, were compelled to choose one of the five official religions recognised by the state. In an interview with Tempo (07/17/2015), Gunarti revealed that her ID card had previously identified her as Muslim on one occasion and as Christian on another. Only in 2010 was she permitted to leave the religion section blank on her ID card. The government's lack of recognition of the Sedulur Sikep's ancestral religion, known as the religion of Adam, led to this situation. Additionally, they were forced to adhere to complicated state administrative procedures for wedding ceremonies, and they faced challenges in accessing public services such as healthcare and electricity.

Besides her thoughts on the economy, Gunarti consistently emphasises that humans are an integral part of nature. She posits that the relationship between humanity and the natural world is a vital force in the struggle. Nature, as she perceives it, is a living entity with which we can engage on an equal footing.

She recounted her experience upon arriving in Rembang, the site designated for the proposed cement factory. She purposefully wandered along the water sources there, and sensed that the surrounding nature remained unaware of the impending threat posed by the cement factory plans. This perspective serves as a local critique of the anthropocentric view that regards humans as the masters and manipulators of nature. Gunarti encourages us to regard nature as Mother Earth, a significant participant in the struggle, rather than merely an object for exploitation.

Gunarti’s perspective resonates with Carolyn Merchant’s ideas expressed in Earth Care: Women and the Environment (1995). This positions women as pivotal figures in the interplay between nature and culture. They serve as the most capable caretakers to guide society towards a more equitable and sustainable future. This inherent connection to nature has empowered women to develop the concept of feminist ethics, a notion that has been persistently examined by numerous scholars, including Lori Swanson (2015), who contends that “it is feminist ethics that binds us to Mother Earth.” This connection arises from women's daily interactions with both nature and their communities.

In this context, women possess a unique epistemological stance. In comparison to men, women are endowed with greater knowledge and possess distinct, often superior, experiences regarding the workings of nature. Consequently, women hold the potential to forge a new ecological paradigm, both in theory and practice. They are regarded as reliable agents, not only because they have endured victimisation but also due to their resilience, survival, and ability to safeguard local wisdom.

Gunarti practises care, not only for her fellow humans but also for nature. She personifies nature as Mother Earth, who struggles alongside us. This idea aligns with the ecofeminist principle of 'more than humans', which prioritises equality among all living beings in an interdependent ecological system. 'I apologise to the rice in my fields for having to attend an event; I couldn't help take care of it', Gunarti stated, emphasising that she regards her plants as living entities endowed of a consciousness and deserving of respect. The primary livelihood of the Sedulur Sikep community is farming, particularly rice cultivation, and they recognise that their lives depend on rice.

Gunarti also expresses gratitude towards the Simbar and Wareh spring caves for their continued provision of water, which is essential for the daily lives of the Sedulur Sikep.