In following the journey of Diponegoro’s keris from a Dutch museum to Indonesia, I encountered the social life of keris as an intimate part of Javanese life.

Objects are carriers of meaning. Especially an object like the keris, which is deeply ingrained in Indonesian culture. The keris is a dagger of great cultural importance, forming part of multiple social relations, from personal relationships to being an object at the heart of national identity. The keris and its human carrier are intimately connected and historically seen as inseparable, creating a unique bond between human and object. The full relational meaning of this object is obscured when it is forcibly taken from its original context. This is what happened when the keris of Diponegoro – the Javanese prince who launched the great Java War (1825–1830) against the Dutch colonial ruler – was seized by the Dutch during Diponegoro’s capture after the war. Since then, the keris of Diponegoro has become a travelling object, connecting the histories of two nations and the stories of people who engaged with it.

As a Dutch student of anthropology with an interest in human and nonhuman relationships in a decolonial context, I traced the historical journeys of the keris of Diponegoro. My interest was sparked by how the keris played a role how the Dutch processed their colonial past. Through my research in Indonesia, I encountered meaningful stories of human-object interrelations in people’s everyday engagements with the keris.

From war trophy to museum object

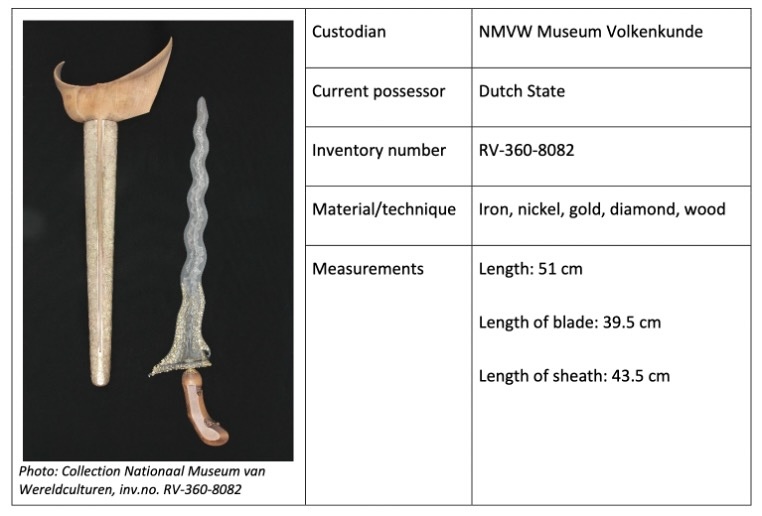

In colonial times, many Javanese objects, including keris, were looted and transported to the Netherlands. It is no surprise then that Dutch students like myself first encountered these objects exhibited in Dutch museums. In this context, Javanese artifacts are reduced to exotic objects to be admired for their craftsmanship but stripped of their social relevance and cultural meaning. In these museum exhibits, the keris is perceived as an inanimate dagger or weapon. For Indonesians however, the keris retained its sacred meaning as living heritage, even after being stolen and stored in Dutch museums for almost two centuries.

In 2020, the keris of Diponegoro became the subject of public controversy. In a ceremony held on 4 March that year, the Dutch King Willem Alexander formally returned the keris to the Indonesian Republic, represented by then President Joko Widodo. A troubling history preceded this incident.

Since 1975 Indonesian authorities had repeatedly requested the return of Diponegoro’s keris. At the time, there was little conversation about restitution. The request for the keris was an unicum, a unique and rare example, marking its importance for the Indonesians. For almost a decade there was no response from the Netherlands to this request. When a search for the keris finally commenced in 1984, it became evident that this important object was lost.

Despite the embarrassing negligence and lengthy delay, the Dutch media presented the object’s return in 2020 as a sign of goodwill and diplomatic celebration. The details of how the keris travelled to the Netherlands and where it had resided since that journey, were not mentioned. Back in Indonesia, there was more controversy, as keris experts questioned its authenticity. Did the Dutch return the wrong keris?

Tracing the keris

Despite the central role of this object in Indonesian culture, the fact was that it was ‘lost’ in the repository of the ethnology museum in Leiden and not looked at for many years. From the North Holland Archive records, we know that this keris was first shipped to the Netherlands in 1830 and subsequently given to King Willem I as a war trophy on 11 January 1831. It was only in 1984, over 150 years later, and after the Indonesians’ request, that the director of the museum, Pieter Pott, began searching for the keris of Diponegoro. These initial efforts at a search were unsuccessful.

In a research report on how the keris came into Dutch possession, Pott hypothesised that the keris was not looted, but instead given to the Dutch as a gift, although there was no evidence presented to support it. The search for the keris was subsequently halted and only resumed in 2017. The illustrious keris was finally identified in 2019. According to Pott, the provenance research was resumed in response to more scientific and media attention for the whereabouts of the keris, along with the museum’s heightened sense of responsibility to investigate ‘contested’ objects. Soon after the keris of Diponegoro was positively identified, plans for its return to Indonesia became concrete. I decided to follow this process, curious to observe how the keris would behave during and after its travels, going from a lost object in a dark Dutch depot to a meaningful object in its native land.

Intimate human-object relations

After studying Javanese objects in Dutch museum collections for a while, in 2023 I was accepted into a summer program on postcolonial dialogue at Universitas Gadjah Mada in Yogyakarta, giving me a chance to trace stories of the keris in its native land. In Yogyakarta, professor of history Sri Margana described how cultural objects are often part of strong human-object relations and that the social practice of an object can reveal much about its meaning. In Java I encountered the keris in many social contexts. In a Javanese household the keris is closely entangled with its human carrier. According to a fellow student, the keris-carrier, as much as possible, carries the keris everywhere, as they are two parts of a whole. Without each other both keris and carrier are incomplete. Even if they do not physically carry it around, the keris retains its intimate relation to Javanese families.

Another fellow student who is from a small village on Java, sent me a video of the washing process of a keris, performed by her father. She explained that the cleaning of the keris is done in the first month of the Islamic calendar, called Suro (Javanese) or Muharram (Bahasa Indonesia). She told me about the ingredients necessary for washing the keris and talked me through the recipe. The mixture includes beaten pineapple leaves, mengkudu, lime and water. The keris is kept submerged in this mixture for a week. During the final step of the cleaning process her father prays for his keris. Every town has its own version of the ritual, she told me.

She further emphasised that the keris should not be glorified, but respected. The keris holds an energy that can be good or bad but, either way, its energy needs to be tended to accordingly. To prevent something bad happening to her family, her father washes the keris at the appropriate time and in the appropriate way, based on the energy of this specific keris. In her household, the keris is kept in a safe place. ‘We don’t need to bring or hold it all the time, because the energy is always with us, without holding it’. In her family, the keris is carried symbolically only on special occasions, like a wedding.

In Javanese material culture the keris is laden with philosophical and cultural values. Professor Sri Margana refers to a bond that is made between humans and human-made objects, generating symbolic interconnections. The keris, present in family households are often heirlooms. A keris can also flow from person to person for various reasons. According to Sri Margana, the keris then connects the stories of their multiple carriers and their contexts.

Experiencing the keris

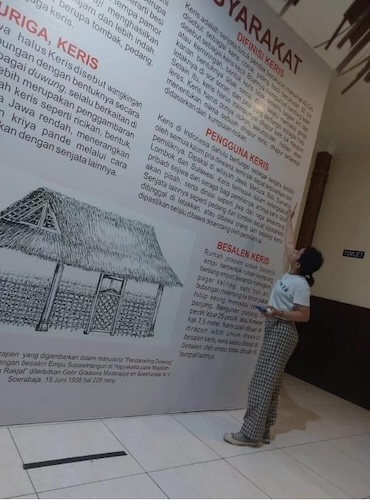

In Java, the keris not only takes on a significant role in family households but also in museums. The city of Solo, for example, has a keris museum. The permanent exhibition in ‘Museum Keris’ provides detailed explanation about the metaphysical layers that are culturally inscribed in this object. Two of my fellow students translated the elaborate textual descriptions of ‘the meaning of the keris in society’ (arti keris di masyarakat). Nowhere in the museums in the Netherlands had I seen any reference to these layers of the keris.

Another example is the well-promoted keris exhibition in a famous Batik clothing store in Yogyakarta, which I visited during my stay in July 2023. This exhibition allows visitors to experience the keris in various ways, which are much less static and more interactive than objects displayed in most museums. The most sacred keris were stored in glass boxes, but an impressive pile of keris was placed on a red tablecloth, surrounded by keris cases and flowers. Many men were gathered around these tables, pen in hand, bidding and discussing. At the centre of the store, a man was making a keris. Neither the keris in the glass boxes nor the making-process were allowed to be filmed, because these special keris and the crafting held a sacred position. Many stories were shared, and the people present around the table were happy to share their ideas with me.

It was there that I touched a keris for the first time. Far from being my first encounter with a keris, I had the unprecedented experience of being part of the social life of a keris, forming my own personal relationship with these objects around me. Their presence in the clothing store and the various forms of display and interaction made them a part of this social context. The keris were actively involved with the lively atmosphere of the store.

Connecting the human-nonhuman

Professor Sri Margana explained that the meaning of Indonesian cultural objects can become obscured when these objects change contexts. During my visits to keris exhibitions in Java, I found that Javanese caretakers make sure that the social life and cultural relevance of the keris are not disrupted when putting the keris on display. Visitors can touch the keris, some can be bought and – by being in their proximity – people are encouraged to share stories about their relationships to keris. The sacred human-object relation remains central.

Arguably, looted colonial objects were ‘taken against their will’. Bring the object back to its hometown, and it is treated differently. Its relations change and consequently so does its meaning. The object will be touched differently, sung to or prayed for. It can reconnect with its obscured relationships and other narratives will flourish. When one looks at a looted object from Indonesia in a Dutch museum the object in this context is tuned to a western understanding, speaking a western language. What I learned is that western thought often overshadows certain meanings of objects from non-western contexts.

The human-nonhuman relations that I encountered in Java showed me something that I had missed in my Dutch academic upbringing: that human-nonhuman relations can present themselves as far less disconnected than I commonly experienced in my western context. In Java, I experienced that objects are actively part of social processes, and that their meanings come about in relational encounters. In these encounters, historical objects do not behave as passive artifacts, but as active social participants. Western institutions have an obligation to acknowledge the way objects can be part of strongly situated social relations when dealing with objects that are bound to formerly colonised cultures.

A journey of reconnection

When I was in Indonesia, the keris of Diponegoro was still under investigation to ensure its authenticity. The keris was part of the exhibition ‘Repatriasi’ with the theme ‘The Return of Nusantara’s Cultural Heritage and Knowledge’ at the Museum Nasional. The catalogue explains that ‘the repatriation exhibition is a way to reconnect the Indonesian people with their cultural heritage, especially since for centuries these objects were kept in the Netherlands and had become detached from their original culture’. The keris - in this context - is addressed by its full name: ‘Kiai Nogo Siluman’ (Kiai means master, Nogo means snake with a crown on its head and Siluman refers to extraordinary abilities). The accompanying narration states that the keris was a ‘silent witness to Prince Diponegoro’s resistance against the Dutch in the Java War’.

The keris was away from home for 189 years. According to the former Director General of Culture at the Ministry of Education and Culture Hilmar Farid, repatriation is not the end of the journey. The journey of the keris of Diponegoro continues too. Now that the Museum Nasional of Indonesia is its custodian the keris will get a chance to develop new relationships, to get reacquainted with its homeland and the Indonesian people and expand its meaning.

Juliana Könning is currently a student of the master’s in anthropology and the research master’s in archaeology and heritage at the University of Amsterdam. She is interested in the social role of nonhumans, and in human-nonhuman kinships.