Thursday, 14 August 2025, was a day of paradoxes. At the State Palace in Jakarta, a full dress rehearsal was underway for the ceremony celebrating 80 years of independence for the Republic of Indonesia. Across the street from the palace, a group of people dressed in black and holding black umbrellas had gathered. Known as the Kamisan (Thursday), they have staged this silent protest every Thursday for the past 18 years, standing against impunity and demanding protection of human rights from the state.

Kamisan may not be as old as the state itself, but it serves as a reminder that a long history of violence has shaped eight decades of Indonesian independence. Kamisan becomes a powerful space for resisting the state’s neglect of these ongoing injustices. Why is this symbolic protest – participants dressed in black, gathering in silence and listening to speeches – a space of power? What has allowed it to endure for 18 years and perhaps even longer?

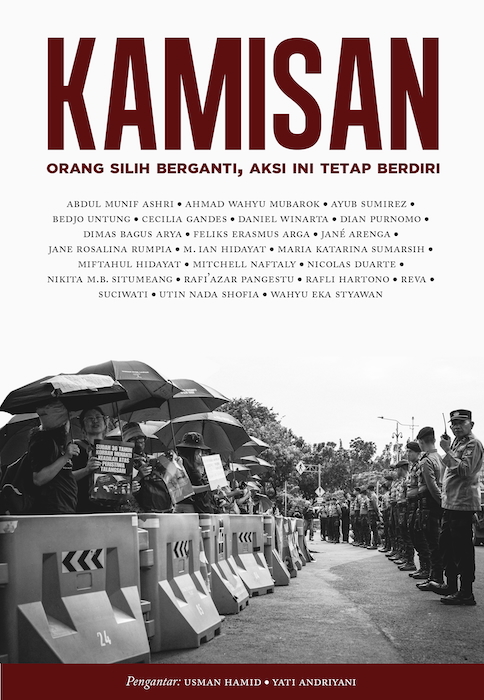

The book entitled Kamisan: Orang Silih Berganti, Aksi Ini Tetap Berdiri (Kamisan: People Come and Go, the Action Stands Firm) may provide the answer. This book does not offer an academic analysis of the human rights struggle. Instead, it provides a forum for concise, honest, reflective and fresh voices from the post-reformation generation - survivors, victims’ families, activists, academics and young people born after the fall of Suharto in 1998,.

Comprising 22 essays, along with two forewords, the contributors share their personal stories, experiences and the significance of Kamisan. This is where the heart of the book lies. It presents the voices of those who initiated or participated in Kamisan, whether across from the palace in Jakarta or in other cities. As Yati Andriyani writes in her foreword, ‘...helping each person write about Kamisan is a simple way of discovering its meaning in its 18th year’.

Interestingly, the book not only presents these experiences through words, but also includes pages of Kamisan photographs taken in cities across Sumatra, Kalimantan and Bali. Printed in black and white, these images are not just historical records of countless weeks of Kamisan protests but also symbols of courage and continued resistance. As Usman Hamid writes in his foreword, Kamisan is a form of resistance that is 'persistent, consistent and grounded in lived experience'.

The Kamisan was initiated by survivors and families of victims of past human rights violations, spanning the period of the massacres between 1965 and 1966 to the violence leading up to the 1998 reformasi (reformation). These protests started on 18 January 2007 in front of the State Palace – seen as a symbol of power – and have taken place routinely every Thursday afternoon since. Collective initiative founded this protest, as reflected in the writings of Maria Sumarsih (mother of Bernardinus Realino Norma Irmawan, known as ‘Wawan’, a victim of the Semanggi I tragedy), Suciwati (wife of the murdered human rights activist Munir) and Bedjo Untung (a survivor of the 1965 to 1966 violence).

Kamisan in turn has evolved across both spatial and temporal dimensions.

In the first dimension, Kamisan continues to advocate for justice for past human rights violations while also highlighting current and ongoing issues in Indonesia’s socio-political landscape. For instance, Pangestu – a young person born during the reformasi era – writes about the historical trauma in his hometown of Tanjung Priok, Jakarta. At the same time, he attempts to raise consciousness about the struggles of his Kampung Bayam neighbours, who were evicted due to a stadium development. In the second dimension, Kamisan is no longer confined to the centre of power in Jakarta. It has spread to other cities, where it focuses on localised social and political issues and has even been staged by Indonesian diaspora members overseas. In Surabaya, for example, Styawan writes that Kamisan addressed issues such as the Kendeng resistance, the criminalisation of activist Budi Pego and forced evictions. Meanwhile in Jember, Hartono recalls Kamisan being held to demand state accountability for the Kanjuruhan Stadium Tragedy in Malang in 2022.

Based on these two dimensions, the book shows how an action that began with a small and limited consciousness was transformed into a broader collective one that transcends space and time. This consciousness no longer belongs solely to victims and their families. It has expanded, replicated across cities and connected with a range of issues. Ken M.P. Setiawan, in ‘Struggling for Justice in Post-Authoritarian States: Human Rights Protest in Indonesia’, describes Kamisan as a form of the ‘vernacularisation’ of human rights. This book sheds light on how an abstract concept is translated into symbolic action in public spaces alongside the lives of ordinary people as a way to resist forgetting, but preserving memory and, most importantly, building consciousness. This consciousness becomes the central idea of the book.

Consciousness emerges in many ways. Some contributors join Kamisan because of family background, past experience, curiosity, reading novels, theological reflection or a personal drive in order to move beyond historical ignorance and political apathy. Many contributors explain how they became aware of Kamisan’s importance in simple terms, accompanied by reflective and critical messages on human rights, justice, the law, equality, feminism and issues such as femicide, silencing dissent, dispossession and agrarian conflict.

Another key message offered by this book is that consciousness is a contextual act. It does not exist in isolation. As Dian Purnomo writes, Kamisan was once held to protest the proposed revision of Law No. 34/2004 in respect to the Indonesian National Armed Forces, just five months into Prabowo Subianto’s presidency. This contextual consciousness keeps Kamisan relevant in line with the ongoing social, political and democratic landscape of Indonesia.. As Suciwati states in her piece, resistance must continue so that crimes against humanity are never normalised.

Even though consciousness often begins as a personal journey, this book implicitly demonstrates that it is also deeply political and significant. Why?

Kamisan is undeniably a collective action, driven by collective goals. However, that collectivity has only formed and endured for 18 years because of the contributions of individuals. It is individual consciousness that compels people to show up, making Kamisan a space of power where silenced, buried and marginalised voices can be heard. Consciousness ensures that past tragedies are not forgotten and current national or local issues are brought to the surface, preventing collective amnesia and the normalisation of injustice. One person’s consciousness encounters another’s. Of course, no one can guarantee that someone will attend Kamisan every single week. After all, victims and their families are growing older. Time is uncertain and loss is inevitable. But consciousness is the first step that brings new people into the fold. As one person leaves, another steps in. People come and go. This process keeps Kamisan standing.

Abdul Munif Ashri, Ahmad Wahyu Mubarok, Ayub Sumirez, Wahyu Eka Styawan, Kamisan: Orang Silih Berganti, Aksi ini Tetap Berdiri (Kamisan: People Come and Go, the Action Stands Firm), Marjin Kiri, 2025.

Riqko Windayanto (riqko.nur@ui.ac.id) has a Bachelor of Arts in Indonesian Literature Studies majoring in Malay Philology from Universitas Gadjah Mada. Currently, he is a postgraduate student in Malay Philology in the Department of Literature at Universitas Indonesia.