The recent crackdown on protests has extended beyond 25 August and indeed beyond the streets

The Indonesian National Police’s response to the August 2025 protests was one of overwhelming force. They arrested more than three thousand individuals across the country accused of involvement in or inciting riots. According to colleagues I reached out to, this crackdown continues quietly. Surveillance has yet to stop.

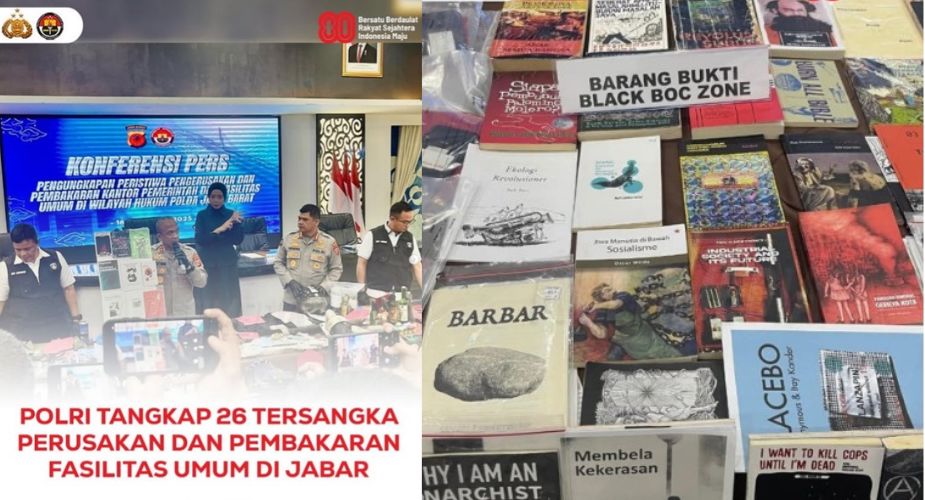

Moreover, this crackdown extended beyond physical detention into the realm of ideas. In a move that perfectly encapsulates panic over thought, the police conducted a series of book seizures from innocent demonstrators in cities like Bandung. The titles taken, including Franz Magnis-Suseno’s Pemikiran Karl Marx (Karl Marx’s Thought, 1999) and Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s Anak Semua Bangsa (Child of All Nations, 1981), were treated not as literature but as criminal evidence.

The reason police gave for confiscating the books, as articulated by the West Java Regional Police Public Relations Chief Commissioner Hendra Rochmawan, was to ‘analyse the suspects' mindset. He elaborated that the books were ‘related to the actions of the rioters’ and suggested a direct, unmediated link between reading material and criminal activity. In an unintentionally comic flourish, he said, ‘They have an anti-establishment ideology… they will attack the government when its policy does not side with the people.’ This very statement is indicative that the police were arresting people who are actually fighting for the public interest and consequently admitting that the police opposed that very interest.

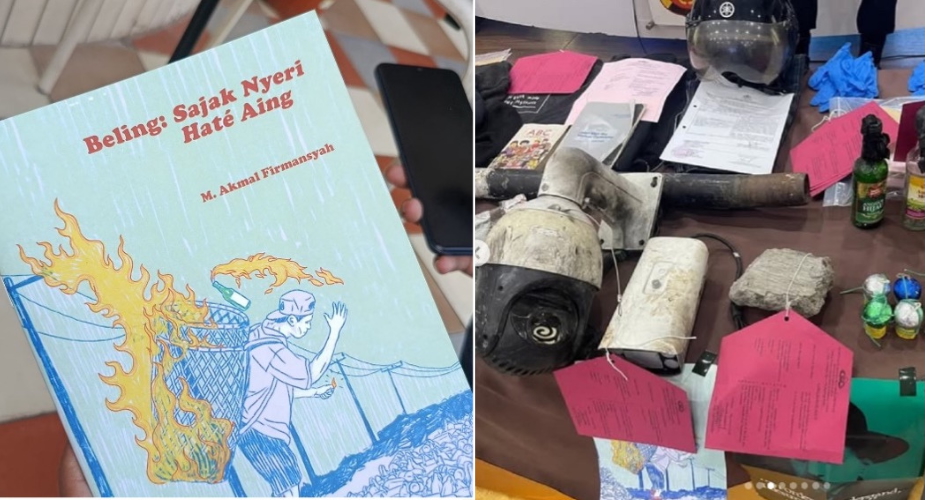

Rochmawan further added, ‘If they keep reading, they might become even more disappointed with the government.’ Well, there is a grain of truth in that statement. More reading can indeed breed more confusion or disappointment. But, if political disillusionment is really the danger, why seize a Sundanese-language poetry zine, Beling: Sajak Nyeri Haté (Shards of Glass: Poems of Heartache) by Akmal Firmansyah, a collection about a man’s sense of inferiority in his love life?

The answer is as simple as the placement of this zine beneath the bottles of Molotov cocktails and rocks also confiscated by the police. The cover of Beling: Sajak Nyeri Haté shows a scavenger picking up a bottle with a burning fuse. I am almost certain the police assumed this poetry collection was a manual for making Molotov cocktails. A very literal case of judging a book by its cover.

A history of censorship

To fully appreciate this shift in book confiscations, one must place it within its historical context. Historical analysis shows that state censorship once followed a very different logic.

In the final years of President Sukarno’s Guided Democracy, the approach to controlling information was characterised less by systematic repression than by political volatility. Official decrees banned books, only to be revoked with bewildering speed. From the Himpunan Surat Keputusan Jaksa Agung Republik Indonesia tentang Larangan Beredar Barang Cetak-Buku 1963 s.d. 1991 (Compilation of Decrees of the Attorney General of the Republic of Indonesia on the Prohibition of Circulating Printed Materials-Books, 1963-1991, 1992), one can see how censorship operated in Sukarno’s era. On Monday books were banned; on Wednesday bans were officially revoked.

The regime lashed out pre-emptively and then retracted when its actions proved untenable. While chaotic and oppressive, this pattern possessed a flickering capacity for self-correction. Its foolishness was situational, and at times, reversible, which shows a system that was unstable but not yet rigid in its paranoia.

The advent of Suharto’s New Order regime replaced this erratic censorship with a far more sophisticated and insidious apparatus. Where Sukarno’s government had acted with nervous impulsivity, the New Order approached censorship with cold, bureaucratic calculation. It institutionalised repression by formally consulting scholars, particularly historians from Universitas Indonesia, to provide an academic justification for banning books.

This process created a veneer of intellectual legitimacy, which transformed raw political suppression into a pseudo-official state assessment. Here lies the crucial twist of intellectual complicity. This was not ignorance but informed repression. The state demonstrated a clear understanding that the most effective censorship requires not just force, but a carefully corrupted scholarship. Cynical, yes, but strategically precise. It revealed a regime that respected the power of ideas enough to meticulously deploy a corrupted form of scholarship to neutralise them.

Following the New Order's fall, its calculated model often gave way to a more decentralised and erratic censorship, practiced by uninformed military commands and religious groups, which echoes the haphazard nature of both the Sukarno and Suharto’s eras. It is against this historical backdrop of erratic panic and cynical calculation that the most recent police action must be measured.

The current police censors have dispensed with any advisory committees or scholarly pretence. They simply confiscated books they demonstrably had not read. This is most glaringly evident in what I’d call the ‘Suseno Paradox’, that is, the confiscation of Franz Magnis-Suseno’s work, a supposedly-critical reading on Marxism, as potential evidence of Marxist-inspired subversion. The police are so uncomprehending of the content they fear that they have inadvertently weaponised an anti-Marxist text. It is censorship reduced to a knee-jerk reflex.

From Sukarno’s spasm of panic, through the New Order’s calculated repression, to today’s repressive seizures, Indonesian censorship has travelled from foolish but reversible, to strategically cruel, to merely clumsy. The long arm of the law is now not just oppressive, but ill-read and embarrassingly heavy-handed.

Taufiq Hanafi (hanafi.taufiq@gmail.com) specialises in cultural politics, knowledge production, and state violence. He has a PhD from Leiden University and postdoctoral experience at KITLV and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

This article is part of a Collection of articles examining the August 2025 protests.