Popular lower-class public meetings in the 1920s were ‘like the salon culture in Europe’, writes Rianne Subijanto in this fascinating historical study of Indonesia’s ‘red enlightenment’. The movement ‘acted like an educational institution’. Her new account of the left wing of Indonesia’s early nationalist movement offers a strong corrective to the narrative that indigenous, especially peasant, resistance in this period was ‘millenarian’, ‘inchoate’, or otherwise benighted.

Enlightenment talk in Europe starts with its most controversial and challenging thinker, the seventeenth century philosopher Baruch Spinoza. Despite concerted attempts by the establishment to muzzle his ideas, his followers built a subversive ideology designed to overthrow the religious, political, and educational assumptions of the European societies of his day, in favour of a freer, more democratic alternative.

Jonathan Israel’s magisterial 2023 biography of the philosopher shows Spinoza insistently transforming politics only through ideas. Rejecting unfocused armed resistance, which could be easily suppressed, he supported ‘planned, structured, meaningful resistance to tyranny and oppression resulting in lasting improved constitutional arrangements.’ Spinoza declared all monarchy and all religious authority a violation of truth. This made him the pioneer of the Radical Enlightenment. When the Italian Marxist scholar-activist Antonio Negri approached Spinoza, he found ‘his Marxist conception of power relations greatly enriched’.

‘Spinozists’ were far more radical than modernisers of the Moderate Enlightenment, some of whom get an honourable mention in the present study: Dirk van Hogendorp, Herman Willem Daendels, Thomas Stamford Raffles, and the ‘Ethical’ administrators of the early 20th century.

In Communication against Capital: Red Enlightenment at the Dawn of Indonesia, Rianne has taken a bold step by depicting the ideas-work done by ordinary peasants and railway workers of the ‘red enlightenment’ as the true avatars of the Radical Enlightenment in Indonesian history, and not some well-meaning colonial officials.

When Takashi Shiraishi memorably named the period up until 1926 ‘An Age in Motion’ (1990), he valued most the spontaneous, somewhat anarchic charisma of the early part of that movement (pergerakan). The heroic (ksatrya) figure of Haji Misbach was central to it. Rianne, by contrast, focuses on the more organised left-wing movement that emerged after the ideological split in Sarekat Islam was complete in 1923. People called it ‘red’ (pergerakan merah); she calls it the ‘red enlightenment’. It was embodied by the radical editor Semaoen, who with a group of organic intellectuals in Semarang, Central Java, ran the newspaper Sinar Hindia from 1918 till its suppression in 1926.

Her book is based on a close reading of this paper. For Sinar Hindia, the pergerakan was not ‘a set of doctrines but … a set of communicative practices’. Its reports allowed Rianne to build a remarkable database of nearly 900 public meetings (openbare vergaderingen). Maps and tables show us where they were held, how many attended, who spoke, what was discussed, and what the ‘rituals’ of the meeting were.

Sarekat Rakjat was the biggest of the communist-affiliated organisations. It may have had over 100,000 members at this time, over half of them peasants. Invitations to meetings stressed freedom of debate:

‘My fellow men and women of all nations and religions. Come! Come! Debate vrij, question vrij, talk vrij’.

Women spoke freely and led these meetings alongside men. Nor were ethnicity and religion barriers to participation. Its salon-like style resembled the nurseries of the European Enlightenment: ‘[T]he salon embodied important characteristics of the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century and developed in line with the rise of print culture’, Rianne observes.

They offered ‘not just the politics of resistance but more importantly cultures of resistance’. Every meeting opened with song and closed the same way. People experienced solidarity, and humanity – keroekoenan, kemanoesiaan. One of its leaders, a woman called Djoeinah, said: ‘Our dream is to live together as one, respecting all ways of being, and overcoming all racial, linguistic, and religious difference’. Violence was never on the agenda. Rianne explains:

Woro Djoeinah saw emancipation as coming not from the transcendental – God or mystical spirits – but rather from something that was immanent: believing in the human capacity to both understand the world and to change it. This reflected the broader structure of feeling of the period in which ordinary communists expressed the new age and consciousness in writing and speeches.… Lower-class native Indonesians wanted to overcome unequal and unjust conditions that were rooted in colonialism, including patriarchy, religion, and aristocracy, but they did so by appealing to human universal and unconditional rights to coexist regardless, or perhaps alongside, their differences.

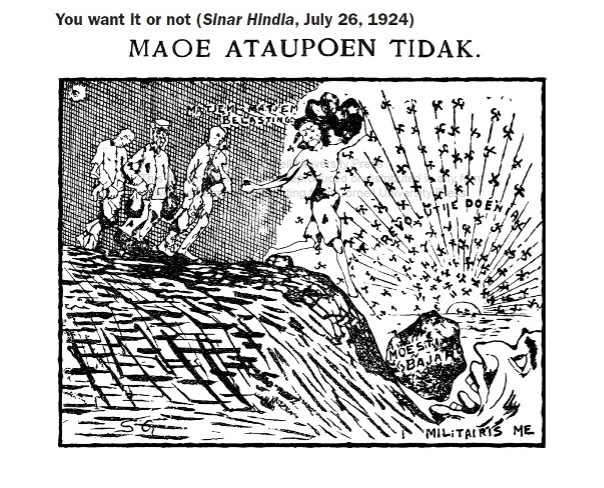

One of the many cartoons collected in the book had this long caption:

Whether we want it or not, people in all capitalist countries must be drawn into the abyss of the heavy taxes that are also sacrificed to the ‘God of War’. Even so, from the abyss of poverty they saw the sun of social revolution decorated with the rays of hammer and sickle getting higher and higher. And that sun will later destroy the God of Capital and the God of War and finally bring about Communism!

In 1927, following several failed local revolts, their movement was banned. Shiraishi said about 13,000 members were arrested (not ‘hundreds of thousands’ as on p.125). We do not learn much about their specific grievances. A list of ‘local matters’ discussed at these meetings seems strangely banal, ranging ‘from lack of rice production, broken bridges, lack of train access, village security, factories versus rice fields, to the cost of hajj (going to a pilgrimage to Mecca)’.

It would be good to know whether their exhilarating sense of keroekoenan and kemanoesiaan could perhaps be read as their defiant No to the disruption caused by colonial labour recruitment practices, to the heightened patriarchy occasioned by new technology, to the neo-feudalism of the colonial bureaucracy, to the ethno-centrism of colonial law. Could it have been their No to the religious mystification promoted by a land-owning indigenous petite bourgeoisie? After the communists left it, Sarekat Islam was increasingly dominated by such landowners, keen to grow rich under colonial protection while keeping the poor in a state of prayerful acceptance of their lot. Moreover, did their solidarity and humanity relate in any way to the earth, in which the lifeworlds of those tens of thousands of peasant members were rooted? Colonial capitalism also threatened the communal subsistence the earth gave them, the ancestors buried there, children and animals born there.

These questions invite more research. Rianne's book stresses the 'universalism' of the Red Enlightenment. It succeeds there: these peasant women and men really did take an active interest in the fortunes of their worldwide movement in China, Russia, and elsewhere in their own archipelago. But this emphasis has come at the cost of looking less intently at their insistent questioning of the immanent power relations they faced every day. It was presumably this that attracted them to the movement in the first place. And it was this questioning that so raised the ire of the colonial powers that they violently suppressed it a few years later.

It’s a tantalising thought: it was not western-educated intellectuals but rather early twentieth century Indonesian peasants who were discovering for themselves the central message of the Radical Enlightenment. One Spinoza-inspired writer, the Australian Arran Gare, described its whole purpose in words they would surely recognise: ‘freedom to do what is worthwhile’.

Rianne Subijanto. 2025. Communication against Capital: Red Enlightenment at the Dawn of Indonesia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Gerry van Klinken (klinken@kitlv.nl) is an honorary research fellow at KITLV, and a member of Inside Indonesia's editorial board.