West Java's popular new governor wants less capitalist exploitation and more tradition

Indonesia is witnessing the rise of a fatherly philosopher king. On 27 November 2024, Dedi Mulyadi was elected governor of West Java in a landslide, winning 62.22 per cent of the vote against three other candidates and sweeping all cities and regencies of the province. Within 100 days of his reign, he had captivated nationwide attention. A poll conducted from 12 to 19 May 2025 gave him an approval rating in West Java of 95 per cent (with 41 per cent ‘very satisfied’). Another poll on 1-5 July 2025 even found that his favourability rating reached a whopping 98.6 per cent. People in West Java affectionately call him bapak aing (my father).

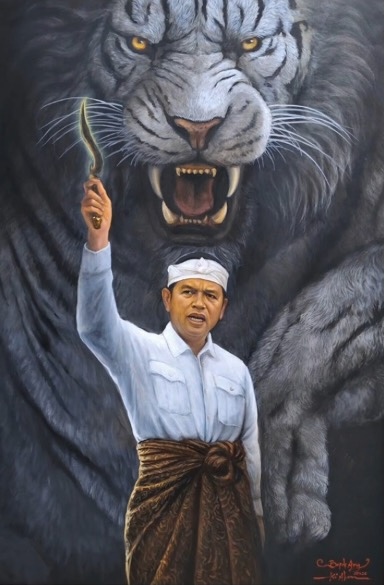

While officially a governor in a constitutional democracy, Dedi Mulyadi’s reign has taken a traditionalist and mystical turn. Long before he became governor, as a traditionalist he already espoused a comprehensive ‘indigenous’ philosophy of religion, environmentalism, and law, blending Sufism with folk spiritual wisdom. Folk religious practitioners see in him the likeness of Prabu Siliwangi, the semi-legendary, deified king of the medieval kingdom of Pajajaran.

Nature

The Sundanese number around 40-42 million people. They inhabit the western part of the island of Java. The vast majority are officially Muslim. While the advent of modernisation has brought a more ‘puritan’ form of Islam, Sufism, the first form of Islam to gain widespread popularity in Indonesia, is deeply rooted in Sundanese society. This is attested by the continued popularity of Pesantren Suryalaya, the centre of Sufism in West Java, as well as the graves of Sunan Gunung Jati in Cirebon and Syekh Abdul Muhyi in Pamijahan, Tasikmalaya.

Traditionally, the Sundanese practised a local spiritual wisdom called Wiwitan. This is centred on nature and holds on to Sang Hyang Tunggal or ‘the oneness of God’. Interestingly, ‘the oneness of God’ in Wiwitan resembles the first ‘high morality’ (sila) of the Indonesian state ideology Pancasila, ‘the oneness of the divine’ (ketuhanan yang maha esa).

Dedi Mulyadi considers himself a Muslim and has said in a widely watched YouTube video that he believes that the Sundanese practised the substance of Islam even before it arrived on the shores of Java. He has never hidden the fact that he also practises Wiwitan as a ‘cultural system’ and ‘science’ to manage the harmonious relationship between humans and nature. He already espoused Wiwitan philosophy while serving as Regent of Purwakarta (2008–2018). This led to accusations of blasphemy, heresy, and Hinduisation by puritan Muslim groups.

His understanding of Islam is not based on the scripturalism of modernist Sunni Islam, but rather represents a blend of Sufism with Wiwitan. He speaks of tauhid, but by this he does not mean transcendental monotheism. Instead, tauhid signifies manunggaling kawula Gusti, that is, to live in unity and harmony with God as the macrocosm. In his words, ‘a person who is spiritually united (bersenyawa) with their land, water, air, and sun is serving their God’.

Thus, Dedi’s religious outlook is immanentist: Allah is the macrocosm as whole, where every element is in harmonious complementarity with each other. He understands the shahada lā ʾilāha ʾillā -llāh (there is no God but Allah) as signifying that all creation continuously glorifies (tasbih) the name of Allah. Therefore, humans cannot feel a connection with God without being one with nature. For him, the peak of being a ‘complete Indonesian human being’ (manusia Indonesia seutuhnya) is manunggaling kawula Gusti. Dedi’s religious philosophy is in this regard influenced by the Sufistic concept of the unity of existence (wahdat al-wujūd). Indeed, he has referred to the manunggaling teaching of Syekh Siti Jenar, one of the Sufi saints who spread Islam on Java.

Intrinsically linked with this immanentist philosophy is a spiritual and traditional form of environmentalism. He invokes a Sundanese ‘theology’ called papat kalimah pancer. This refers to four elements of nature - land, water, air, and sun - that are in harmony and unity (manunggal) to form and foster life. Thanks to the harmonious alignment between these four elements, ‘the Sundanese land is fertile, prosperous, peaceful and harmonious (gemah ripah repeh rapih)'.

Dedi therefore opposes the capitalistic exploitation of nature, particularly mining, on spiritual grounds. In his view, ‘the Sundanese civilisation is not a metal or iron civilisation, but a bamboo civilisation. A metal and iron civilisation requires mining, digging’. For Dedi, humans are not masters over nature, nor are they separate from it. In line with his pantheistic conception of nature, Dedi believes that the ‘ideological root’ of the Sundanese is inherently ‘socialist’ in the sense that ‘there is no personal right to property’. Land is communally owned because ‘everything in nature is entrusted to us; because it is entrusted, our task is merely to cultivate it. After cultivation, [the fruits] are stored (...) and then used collectively’.

In reality, the Sundanese today do not live in harmony with their nature. The Citarum River in West Java has been dubbed the most polluted in the world. There are also around 176 illegal mines in West Java. For Dedi, these environmental issues are exactly the consequence of the Sundanese losing their identity and connection with nature. He regrets that Sundanese children today no longer feel spiritually connected with nature while living in concrete and asphalt; as a result, ‘[w]hen they grow up, they will no longer hesitate to sell rice fields, farms, mountains, forests, islands, even vast oceans, in the name of the economy and prosperity, without the slightest trace of sadness in their face.’ This is why he has made the restoration of nature and closing large mines a priority for his administration.

Law and politics

Dedi lamented that ever since the fall of the Hindu kingdom of Pajajaran in 1579, the Sundanese have ‘lost their self’. In his words, ‘they became a group of people who no longer have [self], no longer know who they are, as a result they follow every new trend, they become dominated, their land has new characters, but these new characters also have no character.’ He spoke of how city dwellers live in buildings with ‘foreign’ design; consequently, the environment also becomes ‘foreign’ and the inhabitants no longer feel ‘spiritually united’ (bersenyawa) with their environment.

He spoke of the same concern with regard to law. Dedi finds that positive law today no longer seeks to maintain the sacred connection between a Sundanese person and their natural surroundings. As a consequence, the laws have become ineffective and have lost their sacred element. Their content is based on an incomprehensible hodgepodge of various schools of thought. He further regretted, ‘Imagine, a law whose content is mixed right, left, middle, what will happen? Meanwhile, what is our self?’

Instead, Dedi supports a traditionalist turn in Indonesian law, where legal norms are based on Indonesian identity and ancestral values. He firmly believes, ‘countries that base themselves on the land they walk on, the water they drink, the air they breathe, the sun that shines on them, and hold firmly to their ancestors—I see that those countries will be developed.’

Dedi considers himself part of the ‘tradition group’ who ‘puts the framework of the ancestors within the constitution’. He believes that the Indonesian constitutional identity is rooted in its past; as Dedi himself put it, ‘the past is embedded in the constitution. Each chapter has its own history, so that it becomes the future. Indonesia builds its future by recounting its past through fiction.’ In this light, it is not surprising that he advanced a traditional philosophy of governance, instead of a liberal conception of constitutional democracy. Dedi explained that in Sundanese culture, the philosophy of leadership is that ‘the tip of the bamboo is inseparable from its lowest stem’ (congo nyurup kana puhu). The leader is therefore called pupuhu, or elder, referring to the lowest part of the plant which is also the oldest. In other words, a leader must be in harmonious unity with their people, and, by extension, the land on which they grow.

‘Just King’

Most notably, Dedi has presented himself as the king of a reconstituted Pajajaran. As governor of West Java, he took an oath in the name of Allah to uphold the 1945 Constitution. At the same time, he also received spiritual legitimacy from the ancestors (karuhun). In a video published on his YouTube channel, which has 8.3 million subscribers, we see Dedi kneeling on the floor deep in a spiritual trance, while facing a female dancer representing the Queen of the Southern Sea (Nyai Roro Kidul), and a male dancer who seems to be possessed by a spirit of the karuhun. This was an ‘ordination’ ceremony (penahbisan). It had supposedly not been performed in Sundanese lands for 500 years.

Dedi has also established his ‘capital’ in his home village, Lembur Pakuan, about 50 km north of Bandung. His residence resembles a royal palace (keraton), displaying traditional Sundanese architecture. The village is well-maintained, clean, and surrounded by lush paddy fields. This is reminiscent of how Javanese and Balinese kings used to adhere to what Clifford Geertz in his book on the traditional state in Bali (Negara, 1980) called ‘the doctrine of the exemplary centre’. The king’s court and capital constituted a microcosm of the universal and political order. Under this doctrine, if the centre is exemplary, the universe and the political order will also be in harmony.

With Dedi Mulyadi having a mystical persona, he has subtly brought belief in spirits and karuhun to the surface, in line with his immanentist worldview. When Dedi went directly to a Christian retreat house that was attacked by an intolerant mob in a village in Sukabumi, a woman in hijab suddenly appeared, supposedly possessed by the mythical figure of Eyang Dalem Suryakencana, demanding Dedi to maintain tranquillity and harmony (repeh rapih). In other words, the revered ancestor was supposedly disturbed by religious intolerance and intervened to restore the harmonious order. This is not the first time that Dedi appeared with a ‘mystical’ encounter; there is an old viral video of him performing exorcism on girls supposedly possessed by a spirit.

Folk religious practitioners have even seen in him the likeness of Prabu Siliwangi, the king of Pajajaran, who is also thought to be the grandfather of one of the nine Sufi saints (Wali Songo) who brought Islam to Java, Sunan Gunung Jati. Many Sundanese today continue to believe that Prabu Siliwangi achieved spiritual liberation (moksa) and turned into a white tiger. For these believers, the signs could not be clearer. A viral TikTok post with 4.7 million views shows Dedi Mulyadi’s feet supposedly matching the preserved footprint of Prabu Surawisesa, the son of Prabu Siliwangi. Folk religious practitioners interpret this as a ‘sign’ that Dedi Mulyadi is the incarnation (titisan) of Prabu Siliwangi himself. A traditional healer in Cigugur, Kuningan, where many Wiwitan practitioners live, even expressed his belief that Dedi Mulyadi is the Just King (Ratu Adil) that was prophesised to put an end to the age of madness engulfing Indonesia.

Pajajaran restoration?

Having long been marginalised by both the educated intelligentsia and modernist Muslims, Sundanese traditions have resurged in the most impressive manner through the figure of Dedi Mulyadi. Benedict Anderson (in his 1990 book, Language and Power) once wrote about Sukarno´s Sosialisme à la Indonesia: ‘[i]t is above all a restoration: the old order re-emerging in technical, modern dress; the Golden Age at a much higher level of average per capita income, but with the older verities and structures scarcely altered.’ This seems to apply here too. Dedi Mulyadi may wear the white uniform of a governor in a constitutional democracy, but his substance is traditional Sundanese.

Pro-democracy activists, such as those writing for the progressive news magazine Tempo, are worried that Dedi Mulyadi is becoming a populist authoritarian leader. They also criticised his king-like rule in West Java. Other observers pointed to how he sidelined the provincial legislature in enacting his policies. Nonetheless, his Wiwitan philosophy also showcases a Global South understanding of environmentalism, which is founded on a cosmocentric spirituality instead of assuming nature as a human dominion, as has been the long-standing practice in the West.

Dedi Mulyadi has shown the powerful appeal of traditionalism in Indonesian politics. The belief in Prabu Siliwangi may seem outdated to a scientific mind. Nevertheless, this cultural phenomenon should not just be dismissed as a mere ‘feudal superstition’. It needs to be studied and taken seriously from an anthropological perspective. Its continued prevalence is a strong indicator of two big questions as Indonesia faces its future. First, is Indonesia able to find inspiration in its own past for an escape from the ecological crisis occasioned by unprecedented capitalist development? And second, does that escape have to come at the cost of an ideal of constitutional democracy?

Ignatius Yordan Nugraha (i.nugraha@hertie-school.org) is a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for Fundamental Rights of the Hertie School in Berlin.