The inside story of Indonesia’s quarter-century involvement in East Timor largely remains unexplored territory

Timor-Leste is heavily dependent on Indonesia’s goodwill. Indonesia is the world’s fourth-largest country by population and surrounds tiny East Timor on three sides; it is the dominant player in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), whose members would likely also deny Timor-Leste entry if Indonesia did. Indonesia is the 16th largest economy in the world, with which the rest of the world, and not least Australia, want to do business. No nation can afford to alienate Indonesia, including Timor-Leste.

In being accommodating towards Indonesia today, East Timor is simply doing what the rest of the world is doing. Australian Prime Ministers Gough Whitlam and Paul Keating did it, and today, to jump forward in time, Prime Minister Albanese is also doing it. He described Indonesia as Australia’s ‘nearest of neighbours and closest of friends’ and gave economic opportunity as the reason for his visit to Indonesia in 2025.

But there’s much more to the story. A very different version of the truth about East Timor circulates in Indonesia. Indonesia has chosen not to pay heed to the Chega! Report, the product of the CAVR, the East Timorese Truth and Reconciliation Commission, but instead, to substitute this for an alternative, self-serving narrative about its time in East Timor.

In summary, this narrative makes out that the Indonesian invasion of East Timor was legitimate, that the war was an internal conflict, that East Timor seceded or broke away from Indonesia in the same way that Aceh once wanted to and West Papua does today, and that Indonesia was not colonising Timor-Leste but doing the right thing there. This version includes the belief that its wide-ranging development program demonstrated not just care for the East Timorese but also Indonesia’s ‘Third World’ superiority over generations of neglect by ‘First World’ Portugal, East Timor’s former colonial ruler. Other rationales are that Indonesia intervened as a good neighbour to restore law and order after the civil war [between Fretilin and the Timorese Democratic Union, UDT], to defend itself, Australia and the region from post-Vietnam communism, to answer an invitation from pro-integration forces, and to reunite a people divided by Dutch and Portuguese colonialism.

The truth is that Indonesia’s war in East Timor was prolonged for dubious reasons, and the Indonesian occupation’s deeply embarrassing end was a policy disaster for Indonesia and for its leaders and caused much suffering to its many dead, injured and deprived. It was nothing to be proud of. When it comes to East Timor, Indonesia ‘lives in a world in which truth is protected by a bodyguard of lies’ (to quote Ian Fleming, author of the James Bond novels).

Indonesia’s narrative about East Timor has significant and contemporary real-life consequences. Moves are underway in Indonesia to declare Suharto a national hero. His former son-in-law, Prabowo, a military heavy, has been elected president of Indonesia with barely a mention of East Timor, even though he served there in the notorious, unconventional Special Forces (Kopassus) at least four times between 1976 and 1999. In 2013, Prabowo used East Timorese Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão’s embrace of him in 2001 to absolve himself of any wrongdoing in East Timor. He told journalists: ‘Would Xanana and other Timorese freedom fighters, our nation’s former enemies, have befriended an Indonesian officer truly guilty of such despicable crimes against civilians?’ Indonesian non-government organisations fret at the growing presence of military officers in the Prabowo administration.

Indonesia is currently preparing a new official history of the country. Culture Minister, Fadli Zon, has said the multi-volume history will be Indonesia-centric, foster a strong national identity and a love for Indonesia, and reinvent Indonesian identity. As the British novelist Hilary Mantel has written: ‘History’s what people are trying to hide from you, not what they’re trying to show you’. The project has generated considerable backlash from Indonesian academics and NGOs. Let us see if East Timor scores a mention in this new official history, and if it does, whether this history will simply exonerate the military.

I accept that Timor-Leste and Indonesia today enjoy a peaceful and positive relationship, the importance of which to Timor-Leste cannot be overstated. I also very warmly acknowledge Prime Minister Gusmão and President Ramos Horta’s consistent and active support for CAVR and its follow-up institution over the last 20 years, not least these days through the state-funded Centro Nacional Chega! (CNC). The construction of a modern archive building will ensure victims’ testimonies are preserved in perpetuity, and CNC’s impressive reparations, reconciliation, education and memorialisation activities continue.

I also accept their policy decision to quarantine Indonesia and confine follow-up to CAVR’s recommendations to Timor-Leste. As President Ramos Horta said in 2009, it is up to Indonesia to deal with its past, and he believes that ‘slowly, gradually, steadily, justice will prevail’ and that ‘Indonesians will bring to justice those who committed serious crimes in Indonesia and Timor-Leste from 1975 to 1999’. CAVR took a similar approach. It recommended that Indonesia, not Timor-Leste, take responsibility for crimes committed by Indonesians in East Timor and that an international tribunal only be established if Indonesia does not comply.

What I question, however, is whether Indonesia and Indonesians will engage in truth-telling when they see the government of Timor-Leste telling them that things have been dealt with, ‘it’s all-over red rover’. President Gusmão put it in this way in his speech when receiving the Chega! Report from commissioner Aniceto Guterres in 2005, ‘The state does not manage the past. The state manages the present and adapts for the future’. Or as President Ramos Horta said in April 2025 in response to a journalist’s question about Prabowo: ‘That is past. It’s already three decades and we do not think of the past’.

I also question whether Dili needs to engage in overkill by dressing up realpolitik and political pragmatism as reconciliation and claiming that the bilateral relationship is a global exemplar that other post-conflict societies should emulate. Following Prabowo’s election as president, Prime Minister Gusmão declared, ‘Our two countries provide a global model for reconciliation and the transformative power of dialogue and trust.’ It is clear from what I have already said that Indonesia and Timor-Leste are not reconciled in any meaningful sense of the word. They get on, but this cannot be described as reconciliation.

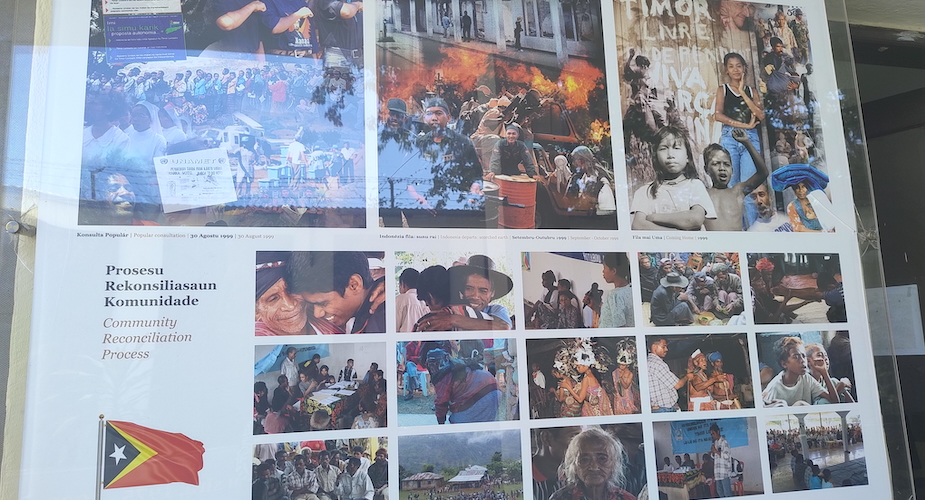

In Timor-Leste, the practice of reconciliation by the CAVR – the only model employed in the new nation - required pro-Indonesia militias to satisfy the communities they had wronged that they had told the truth, were sorry, ready to be sanctioned, and to change. The process drew on traditional dispute resolution practices, notably the presence of a traditional leader who, following genuine truth-telling, welcomed offenders back into the community by inviting them to join him on a woven mat, called biti boot in Tetum. This is the standard against which claims of reconciliation must be measured. Timor-Leste did not extend the practice to Indonesia proper, but neither has Indonesia engaged in anything remotely similar vis-à-vis Timor-Leste. The claim by both governments of having achieved reconciliation actually works against that possibility by degrading the very concept itself. As the old adage has it, you cannot make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.

The Timor-Leste-Indonesia relationship is not a model to be followed by others. It is the exact opposite. Though not intended, it rewards perpetrators and subverts the rule of law, including the credibility of Timor-Leste’s advocacy on that profoundly fundamental principle of truth-telling and for downsides to be acknowledged, not sidestepped or explained away.

Civil society in Indonesia was gutted by Suharto and is still recovering and is again under pressure. It is up to Indonesian universities and researchers, and their Timorese and Australian counterparts, to step up. In a remarkably prophetic observation in 2004, Dr Asvi Warman Adam, then a senior member of the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), told the CAVR: ‘The collective memory of both nations will determine the nature and the strength or weakness of the relationship. This will be reflected in the writing of history by both countries’.

My hope that Indonesia’s universities, in particular, will re-engage with Indonesia’s East Timor chapter is based on my long and active involvement with Indonesia. My engagement has included working at Jakarta’s biggest publisher to publish Chega! in book form (largely funded by the East Timorese government) and the positive experience of presenting that published report, with Indonesian colleagues, to numerous universities from Aceh to Kupang. The inside story of Indonesia’s quarter-century involvement in East Timor largely remains unexplored territory. I hope that it will become a new frontier for researchers and academics.

Pat Walsh is a human rights advocate and author. He is a co-founder of Inside Indonesia, and was an adviser to East Timor’s Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Comissão de Acolhimento, Verdade e Reconciliação - CAVR), and its successor bodies. This article is an abridged version of ‘Reflecting on Truth-Telling’, a talk given at the Broadmeadows Library in Melbourne on 24 July 2025, organised by the Friends of Aileu group.