Indonesians and East Timorese must work together to to face their past and build a common future

The 1975 Indonesian invasion of East Timor and the ensuing violent 24-year occupation profoundly transformed the lives of Indonesians and East Timorese and linked them in complex ways. While the traumatic legacy of conflict has shaped relations, the story is not only one of pain and resentment. Relations between East Timorese and Indonesians are also marked by stories of solidarity and reconciliation. Kinship networks on the island of Timor have long traversed boundaries between East and West Timor and they have remained resilient despite the conflict. In this article, we speak with several Indonesians and East Timorese who have been deeply impacted by these entangled histories and who reflect on their relationships with one another in the aftermath of conflict.

East Timorese leaders’ views

During the occupation, Fretilin, the political organisation leading the struggle to overthrow Indonesian rule, emphasised that the East Timorese fight was not directed at Indonesian civilians. Resistance organisations such as Falintil (the armed wing of the resistance movement) and, later, the national unity umbrella group, the National Council for Maubere Resistance (CNRM) and its successor, the National Council for Timorese Resistance (CNRT), also upheld this position. Mari Alkatiri, former prime minister and Fretilin’s secretary general and co-founder, explained, 'Our goal was national sovereignty and self-determination. Peace and solidarity between Indonesians and Timorese were important in our struggle because our main target was the Indonesian [New Order] regime'.

Colonel Benedito Dias Quintas (Punu Fanu), the director of the Army History Centre of the East Timorese Defence Force (Falintil-Força Defesa de Timor-Leste, F-FDTL), spent 24 years in the jungle resisting the Indonesian army. He echoed Alkatiri’s views on how Indonesian civilians should be regarded. He said that Falintil’s armed struggle was directed against the Indonesian government. Fanu felt that Indonesian civilians, such as transmigrants, who came to East Timor as settlers, should not be targeted for attack: 'We did not attack Indonesian civilians during our struggle, except in cases where they participated in Indonesian military operations against Falintil in the jungle'.

The Catholic Church played a crucial role in advocating for human rights in East Timor by acting as witness and documenting abuses against East Timorese people. Cardinal Virgilio do Carmo da Silva, the Archbishop of Dili, stated that 'the right to self-determination is a fundamental part of human rights and the Timorese had the right to choose their own destiny, including to choose independence'. The cardinal recalled that while some Indonesian intelligence agents had tried to provoke inter-religious conflict by vandalising Virgin Mary and Jesus statues, they failed, because 'we ignored the provocation and appealed for a measured response, even in response to the army’s killing of [young activist] Sebastião Gomes on 28 October 1991 at the Motael Church'. Although most East Timorese are Catholic, the cardinal emphasised the importance of fostering harmony and peace in Timor-Leste for all, including non-Catholics.

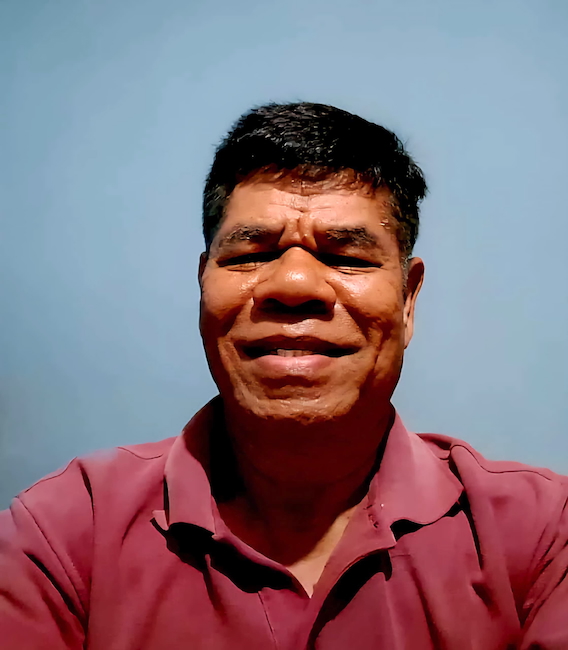

Meanwhile, Gregorio Saldanha, from the 12 November Committee, called for the Indonesian and East Timorese governments to protect the rights of citizens of both countries today. A former clandestine leader, Saldanha was sentenced to life imprisonment by the New Order regime for organising the Santa Cruz demonstration in Dili in 1991. The 12 November Committee represents survivors of the Santa Cruz Massacre in which Indonesian soldiers shot dead hundreds at the Santa Cruz cemetery.

The Indonesian government should look after the East Timorese who have chosen to take up Indonesian citizenship, he said, and regard them as equal to other citizens. At the same time, he added, the East Timorese government should maintain an open-door policy towards Indonesian citizens of East Timorese background who want to visit their families in Timor-Leste. Saldanha praised Timor-Leste’s efforts to foster reconciliation at the community level and between the governments of the two countries. 'Reconciliation is key to fostering a good relationship between the two peoples and for regional stability, especially as Timor-Leste moves towards membership of ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations)', Saldanha said.

Indonesian activists living in Timor-Leste

Today, many Indonesians live in Timor-Leste, conducting business, working for the Indonesian government, and in family relationships with East Timorese. For some Indonesians, the occupation forced them to reflect on their country’s actions in East Timor. One Indonesian, Nug Katjasungkana, described his decision to support East Timor’s campaign for self-determination: 'We sailed in different boats, but had common objectives: independence for Timor-Leste and democracy for Indonesia'.

Nug and his late wife, Titi Irawati (see Rodrigues in this edition), settled in Timor-Leste after the 1999 United Nations referendum. Nug has worked for East Timorese government departments and nongovernmental organisations, contributing his expertise, for example, to the East Timor Truth, Reception and Reconciliation Commission (CAVR) and a women’s history writing project by Fretilin’s women’s wing, the OPMT (East Timor Popular Women’s Organisation).

Indonesian-born former activist Mindo Rajagukguk has lived in Timor-Leste for more than 25 years. She worked with East Timorese political prisoners in Indonesia, including through the advocacy group Yayasan Hidup Baru (New Life Foundation), before serving as an observer during the 1999 UN referendum for the Indonesian solidarity group Solidamor. She returned in 2000. 'I felt that God was calling for me to be here', she said. 'When the country was destroyed by the Indonesian army in 1999, I witnessed what happened. I am proud to be here because I wanted to help the East Timorese - with love - as they needed our help. They suffered so much for many years under Portuguese, Japanese and Indonesian rule.'

Mindo has worked with many government and civil society organisations in Timor-Leste, including the Ministry of Health. She has supported the education of about 20 East Timorese children who have gone on to university, some receiving scholarships to further their studies in Indonesia and Australia. Mindo argued that the East Timorese government should prioritise investment in education, health, and infrastructure, so young graduates can contribute to the nation's development. 'I am here to serve the people of East Timor,' Mindo said, 'and I hope that one day the country will have a great future, free from corruption, collusion, and nepotism.'

Families torn apart

Alongside these stories of resistance and solidarity, the occupation had a profound impact on families. José Maria Barreto Lobato is the only child of East Timor’s first prime minister, Nicolau Lobato (see Kent in this edition) with his wife, Isabel Barreto Lobato. The Indonesian army shot and killed Isabel on 8 December 1975, while Nicolau led the resistance in the jungle and was shot and killed three years later. Nicolau’s remains are suspected to have been taken to Indonesia, but they have never been found. Young José was raised by his aunt, Olímpia Barreto, and her husband, José Gonçalves, an economist and Fretilin Minister for Economic Coordination and Statistics, who later supported the Indonesian administration. The couple moved to Jakarta in 1976 to avoid the Indonesian army focusing on Nicolau Lobato’s heir. José Lobato then grew up in Indonesia without knowing his father’s story. He only discovered his real surname at the time of the 1999 UN referendum, when he saw it on his birth certificate. Being friends with East Timorese students in Indonesia, such as Fernando de Araújo 'Lasama' João Freitas da Cámara, Domingos Sarmento, Abilio Serrano and Pedro da Costa, reconnected him with his homeland.

In 2001, José became a Fretilin member of the Constituent Assembly and served in Parliament until 2005. 'I am so proud to be [Nicolau Lobato’s] son; he made many sacrifices and died for his country,' José said. 'I wish I could have learnt more about him and his vision for the country's future.' He still hopes that his father’s remains may be found and brought back to Timor-Leste so the people can honour him on the soil he had fought hard to defend.

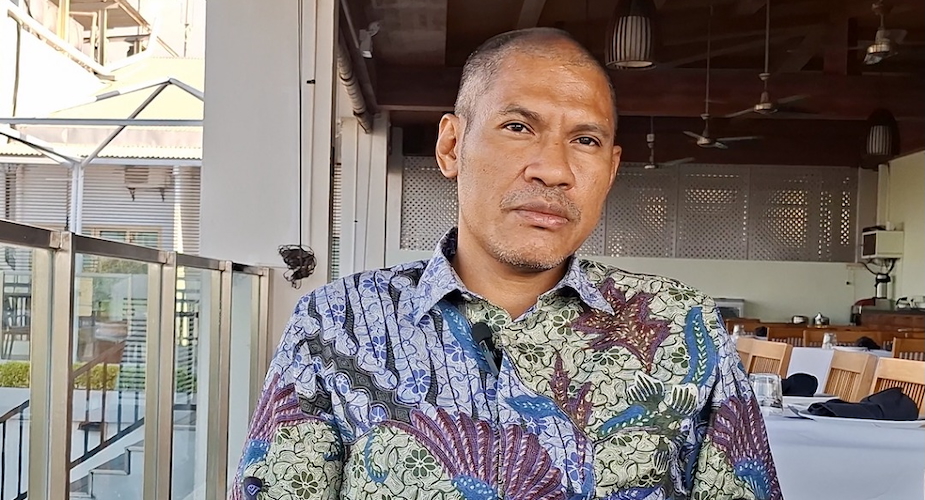

During the Indonesian occupation, Falintil Commander Aluk Descartes (João Miranda) led many attacks on Indonesian soldiers in the Ponta-Leste region. While living in the mountains and resisting the Indonesian army In the late 1980s, Major-General Aluk, now a high-ranking officer in the Timor-Leste Defence Force (F-FDTL), and his wife, Olinda Morais, had a son named Benvindo Azé (also known as Zeromon). Having a small child in the jungle was difficult, as his crying could alert the Indonesian army. Aluk made the difficult decision to leave the one-and-a-half-year-old boy, wrapping Zeromon in a sarong and leaving him on his cousin Feliciano’s farm in Los Palos, in the eastern part of East Timor. He left a note with the child telling anyone who found him: 'Please bring this boy to the Dom Bosco orphanage in Los Palos so they can raise him, and I will take him back when the war is over.' When Feliciano found Zeromon, he took the child to Aluk’s father, Mauresi. Hearing about the child’s arrival, Suryadi, an Indonesian army commander, demanded that he be handed over. Mauresi had little choice. Suryadi left East Timor with Zeromon when his deployment came to an end. The little boy’s name was changed to Shalih Rahman.

After independence, Aluk sought to locate his son through Indonesian and East Timorese army networks. In June 2003, he travelled to Jakarta and met Suryadi, who was by then serving as a member of Indonesian intelligence in Bekasi, Jakarta. Aluk said they felt as if they were meeting as family, not as enemies. They embraced each other. Suryadi took Aluk back to his home and introduced him to his own son, Zeromon, after a separation of more than 15 years. Zeromon met other family members in Timor-Leste four years later.

In 2005, when Suryadi died suddenly, Aluk said he felt a great loss. He reflected: 'In the war, we learned to hate, but there is always a love inside our hearts that we cannot show to everyone. Suryadi and his family had become part of our family.'

These recollections remind us that Indonesians and East Timorese have lived together through a shared history of war and violence and are still grappling with this history’s monumental legacies.

Naldo Rei is the author of Resistance: A Childhood Fighting for East Timor (University of Queensland Press, 2008). He served as Assistant Country Director for the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Timor-Leste and as Chair of the Board of Directors of Timor-Leste Radio and Television (Radio Televisão Timor-Leste, RTTL). Vannessa Hearman is a historian of Indonesia and Timor-Leste based at Curtin University in Western Australia. Her book on East Timorese refugees, titled The Good Sea: The Journey of the Tasi Diak and the Politics of Refugee Protection in Australia, is being published by Melbourne University Publishing.