Despite attempts to re-engineer Indonesia’s governance mechanisms, corruption remains a chronic problem

Luky Djani

Urip Tri Gunawan is an Indonesian prosecutor with a famous nickname: the ‘six billion rupiah prosecutor’. On 2 March 2008 he was arrested by the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) just outside the house of Sjamsul Nursalim, the former owner of Bank Dagang Nasional Indonesia (Indonesian National Trade Bank, BDNI). In his car, officials discovered money amounting to US$660,000 covered nicely in a box. This high profile arrest understandably created a sensation as Gunawan was the leader of a special task force unit consisting of 35 prosecutors appointed by the Attorney General to resolve the longstanding Bank Indonesia Liquidity Assistance (BLBI) corruption case.

Shortly after the monetary crisis struck Indonesia in 1997 the government and the Central Bank (BI) channelled huge amounts of funds to banks such as Bank Bali and BDNI in an attempt to restore public confidence in the banking sector. However, these funds were allegedly used by the banks’ owners for private ends and even transferred to offshore accounts. The overall loss of state funds was estimated to be a whopping 147 trillion rupiah (about US$16 billion). Despite the BLBI scandal coming to emblemise the extent of entrenched corruption at the national level, all attempts by subsequent governments to prosecute those involved had failed to achieve results. Adding to the scandal, only two days before Gunawan’s arrest, the Attorney General’s Office had declared an official end to the BLBI case due to the success of its task force, whom the Attorney General Hendarman Supandji had praised as ‘prosecutors with integrity and courage’.

Corruption remains an ongoing problem in Indonesia despite the dismantling of the former authoritarian system

Corruption remains an ongoing problem in Indonesia despite the dismantling of the former authoritarian system. It is a telling irony that in pursuing its election promise of making inroads into curtailing corruption, Yudhoyono’s government has inadvertently exposed the extent to which it is still firmly entrenched within state institutions.

Catching small fry?

The outcomes of President Yudhoyono’s central anti-corruption strategy of so-called ‘zero tolerance’, formalised in 2005 via a presidential decree, have to date been ambiguous at best. More diligent law enforcement has been one of a swag of strategies employed by the government. However, on average, the time consumed in processing a single case has been roughly two and a half years. Hardly the ‘shock therapy’ some had envisioned.

Compounding the problem, politicians and political parties have used corruption scandals as a political commodity in a bid to increase popularity. The uncovering of corruption scandals has been tainted with political infighting, and not in the context of appropriate ‘check and balances’ among the political parties. There have been many allegations of ‘tebang pilih’, or ‘selective felling’ in the identification and pursuit of alleged corruptors. Those pursued through legal processes have been either the weakest link in a corruption network or a political rival to the government. Whether this has been an intentional political strategy of the government or merely a pragmatic tactic to pursue ‘easier’ cases, the outcome has been increasing public scepticism.

Based on data collected by Indonesian Corruption Watch, from 2004 to 2007 approximately 510 corruption cases were investigated with an estimated cost to the state of nearly 25 trillion rupiah (about US$2.7 billion). Considering the considerable costs to the state, what do we know about those investigated? Those convicted so far have mainly been rank-and-file bureaucrats, local politicians, low ranking Ministry of State Owned Enterprise employees and a token spattering of middle-level businessmen. A few cases have involved high profile figures, such as the case of the misappropriation of off-budget funds involving former Fisheries Minister Rokhmin Dahuri, former Religious Affairs Minister Said Agil Husin Al Munawar and former minister of State Owned Enterprise Laksamana Sukardi. But by the time these cases came to be processed, those under investigation no longer held ministerial positions and consequently didn’t have the strong political backing apparently needed to avoid accountability.

Endeavours to eradicate corruption also show the extent to which ‘anti-corruption’ itself has become both a lucrative agenda and fast growing industry

What about national politicians or corporate tycoons who in the public’s imagination are considered to be at the top of the corruption pyramid? It seems that so far ‘zero tolerance’ law enforcement has not only been discriminatory but has also provided a virtual safe haven for some perpetrators. The late former president Suharto and his family for instance have enjoyed virtual legal protection for years. Conglomerates that were granted special privileges during the New Order regime were either forced to repay their financial debts to the state with their bulging assets, or simply moved their assets and operations outside of the country. Most of their owners escaped legal process and some now live comfortably in other countries. Yudhoyono did remove former state secretary Yusril Ihza and the Minister for Law and Human Rights, Hamid Awaludin, from their ministerial posts after it was alleged they assisted Tommy Suharto use a state bank account to transfer his money from abroad. But this was as far as things went, and no further legal proceedings were taken.

There are several explanations for this inconsistency in law enforcement. Firstly, the government desperately wants to project an image of itself as an anti-corruption crusader. By ‘frying small fish’ the government can highlight the number of cases being prosecuted in the hope that this will boost its overall anti-corruption credentials. On the other hand, corruption allegations against former ministers in Yudhoyono’s cabinet have been conveniently sidelined, as these cases would significantly damage the government’s credibility.

Secondly, the government appears constrained by concerns over the continuing political influence and financial power of Suharto’s children, business cronies and loyalists such as former military chief Wiranto. The failure of Yudhoyono to pursue Suharto while he was alive can also perhaps be partly explained by military tradition. As a junior in military rank to Suharto, it would have been considered a matter of ‘tidak tahu adat’ or not ‘respecting tradition’, if he had pursued legal proceedings against his former military commander-in-chief.

Anti-corruption industry

|

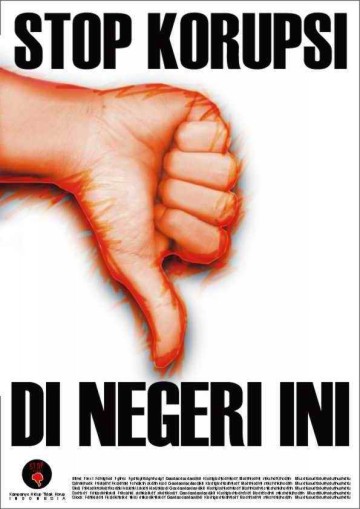

‘Stop corruption in this country’. Anti-corruption poster produced

|

Endeavours to eradicate corruption have also shown the extent to which ‘anti-corruption’ itself has become both a lucrative agenda and fast growing ‘industry’. Since coming to power in 2004, the Yudhoyono administration has adopted the ‘good governance’ paradigm as a platform in combating corruption, a paradigm which has also been at the core of programs promoted by foreign donor agencies such as the World Bank.

In its 2004 analysis of corruption syndromes in Indonesia, the World Bank argued that weakness of regulation, poorly funded public institutions and a lack of well-trained staff were important causes of a lack of public accountability, which inevitably led to corruption. The World Bank report recommended that attempts to bring good governance should isolate vested interests from decision-making processes. By transferring political decisions into the hands of well-trained technocrats, the World Bank argued that debate would focus on substantive issues. This was an alternative to debate becoming politicised by competing vested-interests.

Most of the foreign donors’ good governance programs like those funded by the World Bank follow the formula of political scientist Larry Diamond: ‘There is no way to control corruption without spending money to build institutions.’ This institution-building approach is one also favoured by government officials who, from central government down to the village level, have now become eloquent in the discourse and rhetoric of ‘good governance’. They often consider programs such as computerisation, skills training, and public outreach as little more than additional ‘projects’ from which they can cream benefits.

Recent raids by the KPK on the custom and excise office in Tanjung Priok show that institution-building on its own is not sufficient. The office had been a pilot project of the Ministry of Finance, and was staffed entirely by newly recruited and well-trained officials with a reputation for honesty, who had been selected from other customs offices. In order to avoid temptation, their salaries were tripled and rigid monitoring and evaluation mechanisms were put in place. Despite this, the KPK found evidence of ‘grease money’ from business counterparts and the existence of an extra-legal ‘parallel system’ whereby decisions were negotiated via a complex network of middlemen and under the table deals.

Programs such as computerisation, skills training, and public outreach are little more than additional ‘projects’ from which they can cream benefits

These cases show that the government’s anti-corruption initiatives have been both ineffective and counterproductive. Good governance programs have been welcomed not only because of the huge ‘incentives’ in term of funds provided by donors, but more importantly because the programs do not significantly jeopardise the entrenched interest of existing politico-business networks.

A way out?

There are at least two ways to help rectify this situation. First, there needs to be an overall shift in the approach towards combating corruption. In order to be effective, strategies must start by tackling the fundamental causes of corruption, for example, the collusion of interests between public officials and the business sector. To counter this, decision-making regarding the allocation and distribution of public resources must include the public at large. ‘Accountability’ needs to be understood as an ongoing process involving direct participation and consultation with the public, rather than simply the tabling of accountability reports by public officials.

Secondly, greater resources need to be directed to the Indonesian Anti-Corruption Commission (KPK) as the leading agency in combating corruption. Currently there is still a lack of coordination and leadership in anti-corruption measures. Those very institutions entrusted with upholding the law and tackling the corruption epidemic, such as the Attorney General’s Office and the Ministry of Public Administration Reform have proven not only incapable and ineffective, but also tainted by corruption and conflict of interests themselves. ii

Luky Djani (lukydd@yahoo.com) is a researcher at Indonesia Corruption Watch and is currently doing a PhD at the Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University.