Encountering Indonesia through the Buru Quartet

Nathan Hollier

In Max Lane’s penetrating work Indonesia Out of Exile: How Pramoedya’s Buru Quartet Killed a Dictatorship there is a description from Pramoedya’s publisher, the late Josoef Isaak, of how he felt when he first read the manuscript for Bumi Manusia, This Earth of Mankind, the initial novel of what would become the quartet. ‘I can’t describe it in words,’ he said. ‘It made me feel alive again.’

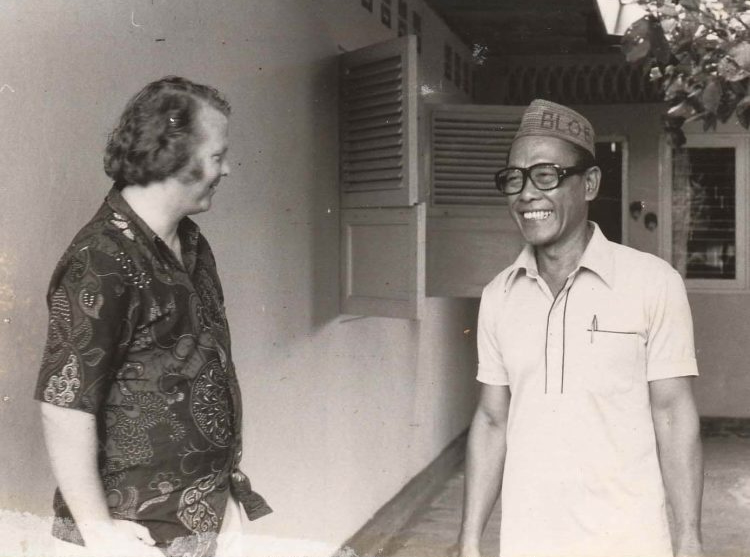

Josoef read this work following his imprisonment in Jakarta for ten years without charge under Suharto’s New Order regime. He encountered a gripping and illuminating story of the origins of his people as a nation, a story with profound implications for him and his fellow Indonesians in the struggle that, at the end of the 1970s, he knew lay ahead. Indeed, he would have realised that this manuscript would or could itself play a vital part in this struggle when it was published by the company that he was courageously, dangerously, about to get going with Pramoedya and Hasjim Rachman: Hasta Mitra (Hands of Friendship).

Given this context it is perhaps a little ridiculous to admit, but Josoef’s description of how he felt when he first read this work resonated with me. Reading This Earth of Mankind novel gave me a feeling of coming alive again also. And as I read the subsequent novels of the quartet, in Max Lane’s translation, this feeling of being inspired and, more than that, enlivened, given a new impetus and purpose, kept recurring.

I will reflect briefly here on why and how; to say something about the power of Pramoedya for Australian readers.

In the Buru Quartet, Pramoedya shows us the Indies from the end of the nineteenth century through to the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, an inchoate Indonesia, through the eyes of a remarkable character … Minke … a character who could only be created by a most extraordinary author. Minke is a name given him by a Dutch teacher. The character’s original name is ‘Gus’.

Minke is a captivating, magnetic and inspiring character for many reasons but perhaps most profoundly, most powerfully, because he is a ‘native’, to use the terms of the day, who is able to see the value and learn principles and teachings of the European Enlightenment and then use this knowledge against his teachers, the Dutch, who justify their ongoing mastery of the Indies peoples through the argument, more often assumed than stated, that they are more civilised than those they have colonised, that they and other Europeans are able to acquire and appreciate knowledge and beauty in ways that the Indies peoples cannot.

The spuriousness of this justification of colonialism is revealed progressively throughout the novels, as the Dutch are forced into overtly perfidious and barbaric behaviour to maintain their dominant social position, a position underpinned not by any superior cultural or intellectual capacity but by their greater educational opportunity, wealth, and ultimately guns and money. This is dramatised extremely powerfully at the end of Child of All Nations, the second novel of the quartet, where Engineer Mellema, the only legitimate child of Herman according to Dutch law, who has overseen the death of his half-sister, Minke’s wife Annelies, returns to the Indies to take possession of the agricultural business owned by his father, now deceased, but entirely developed by his father’s native concubine, Nyai Ontosoroh, Annelies’ mother.

Nyai, originally named Sanikem, a person of great intellect, learning (initially from her Dutch master, the father of her children) and moral clarity, is perhaps Minke’s greatest teacher. The novels are in some ways structured by the people he meets and who pass on to him and, through him, us, important information and powerful wisdom. His second wife, for instance, the Chinese migrant activist Ang San Mei in the third novel, Footsteps (1985) told the narrator:

'The English have brought so much trouble to the world … Empress Tz’u-hsi could not hold them back. In fact, she’s ended up working with them. But we can now count the days that Europe will reign over the coloured peoples.'

That was the first time in my life that I had ever heard such an idea.

'There have been so many Europeans who have caused so much suffering in the world'. She told me about Sir John Hawkins, the Englishman who pioneered the slave trade between Africa and America, so that forty million Africans ended up dead or condemned to a life of slavery.

And I had never come across this story before. I had never heard it from anyone or read it anywhere, in school or outside.

Later, Minke diagnoses:

There were many ways, it seemed, to steal someone’s country. And the objective was always the same—to win the race being run by all the colonial powers of the world to see who was the greatest thief, the greediest, the best at sucking up the riches of the earth and its peoples. It made me sick.

Then one day: 'It would be ideal, of course, if the Indes were unified,' said a journalist, 'but won’t it mean a great burden for the government?'

Van Heutsz [the Governor-General] didn’t answer. Instead he made the following pronouncement: 'Those who resist will pay dearly for their resistance.'

'What do you mean "will pay dearly"?'

'As it was after the Padri War and the Java War. West Sumatra and Java were subjected to a system of Forced Cultivation.'

'But the people of the Suna Islands, and of the Moluccas and Central Celebes, and of Sangir and Talaud are not known as farmers.'

'They will soon learn to be very fine farmers.'

Then came another idea, no less sharp than the first: 'If the Korte Verklaring was inspired by Christian values, then why was it military methods that were used? Why weren’t they helped instead with priests, teachers, engineers, and money?'

But the government knew only the methods it had used ever since first setting foot in the Indies.

'This is the only way they will come to understand the good and honourable intentions of the government. Crime and sin must no longer be allowed to flourish in these small states, which have not yet subjected themselves to the authority of Her Majesty. Financial help? The people of the Indies have always been corrupt. Corruption is a part of their mentality, whether dukun or trader, peasant or king. They do not understand the value of money. They only understand the needs of their own lust. Only the power of the Netherlands Indies can educate them.'

In 1898, the Korte Verklaring (lit. short treaty) acknowledging Dutch rule replaced more complicated treaties with Aceh. The treaty was introduced by Snouck Hurgronje, advisor to Van Heute, the new governor of Aceh. The scientific and aesthetic achievements of the Dutch and Europe are also, at times, put in an international context commonly misrepresented by the colonial powers and its defenders, with Minke’s coming to learn of the vital contributions of Eastern thinkers and artists to advancement in these fields, and of the struggles of Eastern peoples, such as the Filipinos, for independence and self-government.

At the same time, Minke is able to remember that the Indies peoples need to learn from science and the outside world and avoid the temptation to idealise a pre-colonial past. The new Indies nation, which he comes to conceive of, is avowedly a new entity, a new creation. In casting off Dutch colonial power, Minke recognises that it would be a step backward to then re-impose traditional Indies social forms and patterns, with their own tyrannies, inhumanity and ignorance. This is conveyed with great clarity through his justifiably rebellious feelings towards his father, a bupati, a little royal, who, in spite of Minke’s education and achievements, expects him to behave as a lowly supplicant.

In the manifestly unfair colonial circumstances and experiences of Minke and the Indies people of these novels, the true nobility of his democratic, secular, rational, nationalist ideals, obtained and refined through his learning from many people across the quartet and expressed in the organisation of the Sareket Dagang Islam or Islamic Trade Union, is very affecting.

For an Australian reader, the impact of encountering this story is heightened because one necessarily faces the fact, with some shame, that we as Australians have in general had little engagement with Indonesia, our near neighbour, over so many decades, in spite of the fact that, as Pramoedya shows in the character of Minke, the Indonesian people did not choose for themselves the traditional rural lifestyle that I think Australians commonly assume to be the ‘natural’ lifestyle of Indonesians.

Rather, as Max relates in Indonesia Out of Exile, and as other scholars have shown also, Indonesia’s historical pathway after the rise to power of Suharto in 1965 reflected the powerful counter-revolution of the New Order and the imposition by this regime of Suharto’s pre-Enlightenment, anti-democratic ideal of the rural population as a depoliticised ‘floating mass’ detached from any political party.

Suharto’s approach to government is reminiscent of that of Salazar in Portugal and was similarly influenced by Catholic, anti-Enlightenment thinking. It is not often remembered that the Muslim Suharto leadership was strongly influenced by Indonesian Catholics who came out of the anti-Reformation, anti-liberal, pre-Vatican II milieu of elite Jesuit schools such as Canisius College (Kolese Kanisius) and university student groups such as the Association of the Catholic Students of the Republic of Indonesia (PMKRI).

An Australian reflection

For Australian readers, the Buru novels also inevitably, and very pertinently and usefully, prompt us to ask ourselves how the Enlightenment project is going in our country. Do we venerate the arts and sciences? Education? Democratic principles? Do we insist on the inalienable value of all human beings?

For the colonial Dutch, these were at least questions to be taken seriously. Thus, in This Earth Minke’s favourite teacher, Magda Peters, is able to concentrate her students’ minds on literature by suggesting to them that without a love of literature they cannot be considered civilised people ‘You will all advance through school. Perhaps you will obtain a string of all sorts of degrees, but without a love of literature, you’ll remain just a lot of clever animals’.

Are we Australians succumbing however happily or unhappily to anti-intellectualism, vocationalism and materialism, authoritarianism and exclusionary and defensive forms of nationalism?

As Australians, the Buru Quartet also asks us: What role have we played and what role do we play in the Enlightenment project, which is properly an anticolonial project, at the international level? Minke and Pramoedya raise these questions for us especially powerfully because they are people with much, much more of an excuse than we have as Australians to leave such questions unasked. In asking such questions they risk their lives, whereas we only risk, at most, our careers.

In early 1941, during the Second World War, Australian Prime Minister Menzies flew to London from Melbourne. In those pre-jet-engine days this entailed quite a number of stops at British consulates, with the first being in Jakarta (before going on to Singapore, Thailand, India and other places). In Jakarta, Menzies had a ‘long talk before dinner’ with the Dutch Governor, Van Der Plas, ‘a handsome, active, and intelligent man’, as he recorded in his diary, who ‘said some shrewd things worth noting’, notably about the value of an ‘empire’ for ‘Holland’ and Britain.

For Menzies, clearly, there was no sense that the sun might justifiably set on the British empire and European colonialism: ‘[A]t every stopping place,’ he records later in the journey, ‘I am impressed by the cool, youngish, educated and good-looking Englishman who materialises whether as Resident, Commissioner, Law Officer, adviser to the local Sheik … or whatnot. These mysteries under which Englishmen hold posts of authority in non-British countries are quite beyond me, but the breed is superb.’

Ben Chifley, a great admirer of Nehru, led an Australian Labor government of 1941–1949 which supported Indonesian independence, but since that time the Australian government’s international role in its region and elsewhere, writ small in the unctuous 1975–1978 term of our Indonesia ambassador Richard Woollcott, has broadly been to support colonial and neocolonial power. As Professor Clinton Fernandes has argued powerfully, the organising principle of Australian foreign policy is to demonstrate the nation’s relevance to the imperial centre – formerly Great Britain and now the United States – so as to ‘stay on the winning side of the global contest … described variously as [between] imperialism versus anti-colonialism, developed versus developing countries, liberal democracy versus the rest, the North-South conflict, core versus periphery, Europe against the Third World, and so on’.

In Child of All Nations, book two of the quartet, Nyai Ontosoroh, whom Minke calls Mama, says to him:

Everybody in authority praises that which is colonial. That which is not colonial is considered not to have the right to life, including Mama here. Millions upon millions of people suffer silently, like the river stones. You, Child, must at least be able to shout. Do you know why I love you above all others? Because you write. Your voice will not be silenced and swallowed up by the wind; it will be eternal, reaching far, far into the future. As to defining what is colonial, isn’t it just the conditions insisted upon by a victorious nation over the defeated nation so that the latter may give the victor sustenance—conditions that are made possible by the sharpness and might of weapons?

For me, as a publisher and as a person, the story of Minke, of what he sees, experiences and learns, told across the Buru quartet, is enormously inspiring, illuminating and powerful, including in the sense that it provides us with guidance, even, about what we should do and what we should not do in our world, and our nation, still shaped by colonialism and imperialism.

Through Minke, Pramoedya will go on being heard, will go on giving life to those who care about genuine human connection and development, our rightly most treasured ideals. Pramoedya’s achievement is an astonishing one, and I am grateful to have the opportunity to help keep the memory of his achievement fresh in our minds.

Nathan Hollier is manager of ANU Press and he writes on society, culture and economics in Australia and its region.