5,180 nights captive

Joel Whitney

On the night of December 14, 1977, Pramoedya Ananta Toer woke to someone knocking. Lighting his lamp, he opened the door and found a prison worker, out of breath. ‘Your name is on the release list,’ he said. ‘You should be ready in case you have to leave tomorrow.’ Pramoedya received this message with caution, recalling past rumors of release that had gone unfulfilled. Over twelve years of imprisonment, eight of which were endured here on Buru Island, it had been painful to indulge in false hope. But in the days that followed, journalists visited more freely, an auspicious sign for someone who had been arrested in the middle of the night, surveilled during his imprisonment and banned from writing even letters, and who was the most famous literary supporter of the ousted President Sukarno. One young journalist visiting in the aftermath of the breathless promise of release, Sindhunata, let slip that he had visited Pramoedya’s family before coming to Buru. He confirmed for Pramoedya that Maimoenah was still beautiful, and had been selling ice snacks and cakes to make money, and that the children were doing well; his daughter Astuti would go to university soon.

‘But do you think my wife and children really want me to come home?’ asked Pramoedya.

‘Of course they do. They really love you,’ answered the journalist, his voice breaking. Sindhunata also refuted the idea that Pramoedya’s wife had remarried, a lie Pramoedya had been told. In fact, she was waiting for him, he said. ‘I hope we will not be disappointed again,’ she wrote in a letter Sindhunata had promised to deliver to Pramoedya. Though officials had initially suggested that Pramoedya would leave with the first group to go home, the reality was that Maimoenah would have to wait two more years for her husband’s release. When Pramoedya watched the first fifteen hundred newly freed prisoners sail away, he was happy for them, but disconsolate for himself. It was all part of an ordeal that saw him and his others his and twenty other units forced to endure gruelling physical labor, grow their own food or eat lizards, worms, rats, snakes and even a newborn’s placenta for protein, face beatings for possessing pen or paper, and finally–in the case of Pramoedya–nearly get shot for wearing improvised shorts when his own work clothes wore out.

Additionally, he would be interrogated by military officials and fellow journalists like Mochtar Lubis, who was a member of the CIA front, the Congress for Cultural Freedom: ‘Have you discovered God?’ Lubis once asked in a junket in 1973, and went on to prod him over the events of September 30, 1965, of which Pramoedya obviously knew nothing. And after having been arrested at night two weeks after the mysterious military coup, these informal interrogations by fellow writers–aren’t exercise and forced labor virtually the same? one asked, belittling his trauma–would prove to be the closest he ever came to a trial. But, worst of all this injustice had been his inability to write his literary masterpiece recounting Indonesian independence, although this restriction loosened somewhat after 1973, and his cruel separation from Maimoenah and his children, exacerbated by a rumour that she had remarried.

Finally, in 1979, thanks to pressure from Amnesty International, advocacy groups in Indonesia and US president Jimmy Carter, who would soon campaign for a second ‘human rights’ presidency, Pramoedya and his cohort of die-hard, supposedly ‘Marxist’ prisoners were told to pack. But before he—or anyone else, for that matter—could rejoin their families, they were forced to sign two documents. The first included promises never to ‘spread or propagate Marxist-Leninist communism… upset security, order and political stability… betray the [Indonesian] people and the state… initiate litigation proceedings against nor demand redress from the Indonesian government.’ The second pledge was an acknowledgment ‘that they were never tortured and never had to undertake forced labor.’ With no other choice, Pramoedya signed both.

However, leaving Buru did not mean total and unrestricted freedom. Before his release, Pramoedya learned that he would be subjected to indefinite house arrest under the watchful eye of the regional police. His ID would be marked ‘ET,’ for ‘ex-tapol’—tapol being the Indonesian abbreviation for ‘political prisoner’—and he would not be allowed to publish his writing. Upon arriving in Jakarta, though, he would break each of the conditions of his release.

On November 12, 1979, during the island’s seasonal rains, Pramoedya boarded the Tanjung Pandan, a decrepit troop ship. After three days at sea, Pramoedya, the schoolteacher Tumiso who shared his barracks, and some forty other ‘die-hards’—who had all failed tests that were supposed to demonstrate their willingness to live happily under authoritarianism—were separated from hundreds of their comrades and sent aboard a small landing craft to Surabaya in East Java. From there they were bused west to the largest military base in Central Java and checked for contraband.

Like others, Pramoedya carried his clothes in a sack, along with his exercise mat and prayer mat. He was searched—his manuscripts had already been confiscated by Buru’s prison guards before he left—and he made it through. As the line crawled forward, Tumiso collapsed. Upon reaching the guard post, he told the guards he was sick, and they called him a filthy communist coward. At the next checkpoint, the affable farmer fell again, until he reached Semarang, where, again, he faltered. In fact, Tumiso was being strategic and intentional: Each time he stumbled, the guards, distracted by the ensuing chaos, would fail to check his rucksack, which contained the manuscripts that would become the Buru Quartet. Tumiso’s sickness was a ploy to protect the famous Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s writings.

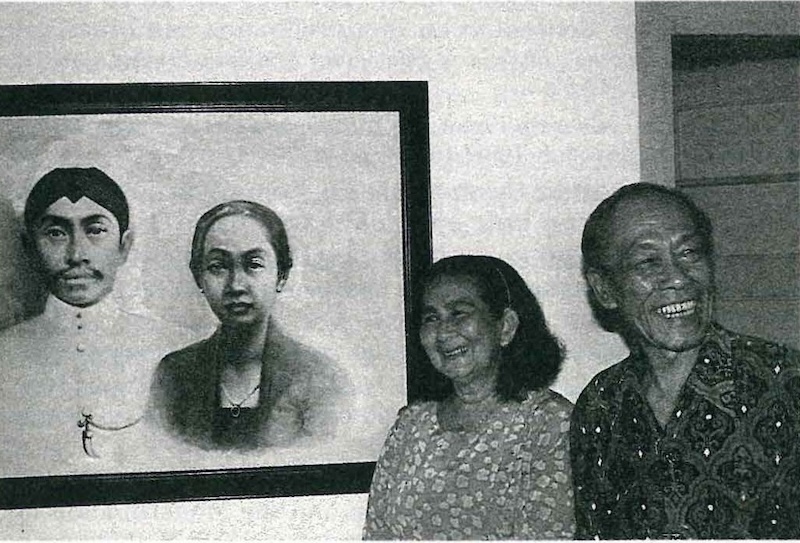

Six weeks after leaving Buru, both Tumiso and Pramoedya were released. When Pramoedya’s family came to escort him home, he was confused by their faces, having spent 5,180 nights as a captive. Merely an image in Pramoedya’s mind for the past fourteen years, Maimoenah finally stood before him in the flesh. It was just as the young journalist Sindhunata had said: she was still beautiful, and he was relieved to see the old love in her face, a love he’d feared was gone. Beside her was a young woman he did not recognise, who shouted, ‘Papa, papa!’ He remained mute and unable to move. Again, she shouted, ‘Father!’ He gasped, realising at last who was calling him: Astuti! When he had been taken away to Buru, Astuti, his fourth child, had been twelve years old. Now she was twenty-three. The faces of his children, which had been frozen in time on the island, had morphed into those of young adults.

Still dazed, he hugged them. Long ago, he had promised Astuti he would lift her upon his release. She was much bigger now. But he was in good shape. ‘Feeling strong?’ she asked him. He nodded and stepped toward her.

A banned bookseller

In early 1980, weeks after his release, Tumiso traveled to Jakarta and handed Pramoedya the contents of his rucksack: one of six copies of This Earth of Mankind and its sequel, Child of All Nations, the documents he had feigned an illness to protect. In case Tumiso’s copies were apprehended, though, five other prisoners and a priest had also smuggled out copies. Among them was Pramoedya’s friend, former editor at Eastern Star and unit-mate Hasjim Rachman and a Catholic priest on Buru named Roovink. Just months after their release, Rachman, Pramoedya, and another former prisoner, named Joesoef Isak, decided to launch a publishing house called Hands of Friendship. Their first book would be This Earth of Mankind, which, along with its sequel, had been fully drafted and edited on Buru before Pramoedya and Rachman’s December 1979 release. (The third and fourth books had been conceived and outlined on Buru but were finished during the years of Pramoedya’s house arrest.)

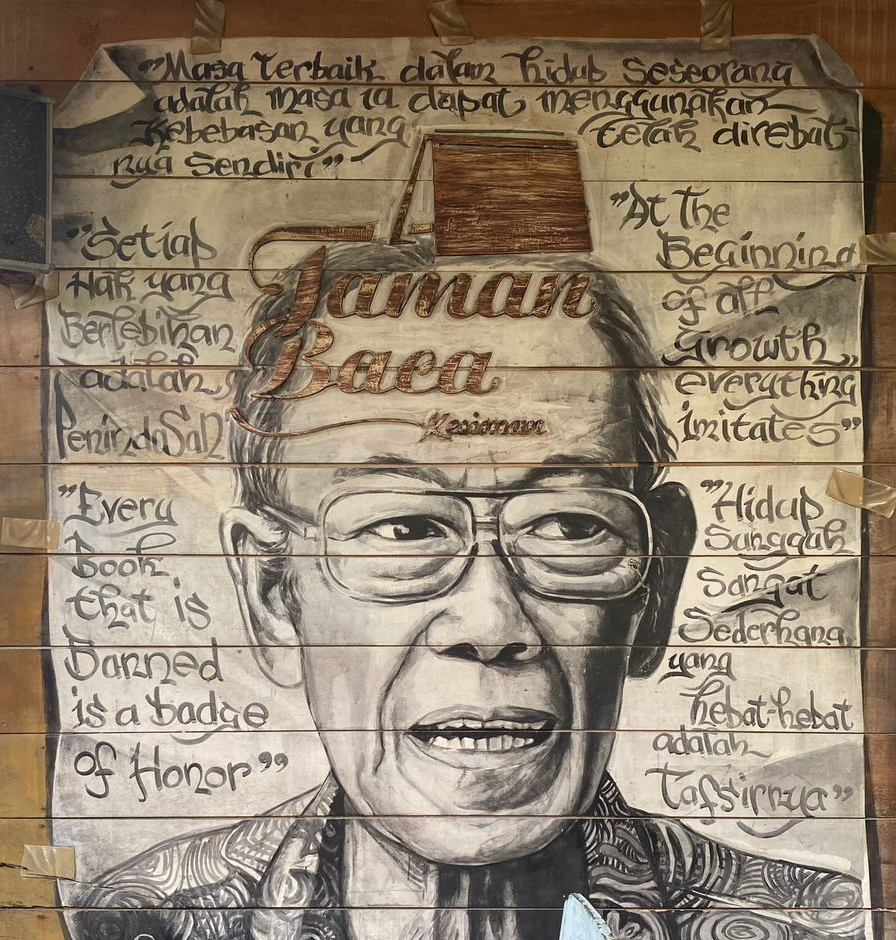

Upon This Earth of Mankind’s release in 1981, the novel shattered national sales records, and within a short time, it was banned. The ban was toothless—at first a mere letter from the government asking Hands of Friendship to halt the book’s publication. Rachman and Pramoedya refused to acknowledge the demand. But with the release of the second novel, Child of All Nations, the dictator’s cohort of uniformed apparatchiks enforced the ban. They raided Java’s booksellers, confiscating the novels, and Isak was hauled before the authorities and berated. Their efforts were not entirely effective, as novelist Richard Oh pointed out in an interview. Oh was one of many Indonesians who read the novels in xeroxed samizdat. It thrilled him to read books that had to be tracked down through word of mouth and acquired illicitly. The ban had the opposite of its intended effect: instead of suppressing Pramoedya’s tale of collective action to end colonialism, it amplified the Quartet’s mysterious power.

Though it was still banned in Indonesia, This Earth of Mankind appeared in English in 1992, in Max Lane’s translation. Barbara Crossette, who reviewed the novel in The New York Times, called it ‘a lesson in the complex psychology of colonial life—of both the colonisers and the colonised. There are few one-dimensional ‘good’ or ‘bad’ characters here.’ When the book started winning awards, Pramoedya had to send emissaries to accept them. ‘Every award for me is important because it means a slap against militarism and fascism in Indonesia,’ he told an interviewer. He was first nominated for the Nobel Prize in 1986, and though he received several subsequent nominations, he ultimately never won. The most prestigious prizes awarded to him were the Fukuoka Prize from Japan, the Ramon Magsaysay Award from the Philippines, and two PEN Awards from London and New York, including the PEN Freedom to Write Award of 1988.

Awards meant that the Quartet’s politics could not be sidestepped. When he won the Magsaysay, his old rival Mochtar Lubis wrote an open letter protesting the choice of a tapol, a former Buru political prisoner, as its recipient. The late president Sukarno’s daughter Sukmawati was one of several hundred who signed a letter in support of Pramoedya. Widji Thukul, a poet who would lead protests to topple Suharto as a part of the movement called the Reformasi (the Indonesian word for ‘reform’), also signed. Like Thukul, many of the Reformasi’s leaders, who demonstrated to end Suharto’s dictatorship and usher in democracy, were inspired by the Buru Quartet.

Reformasi activist Budiman Sudjatmiko credits the great saga written in the labor camp for ‘opening our eyes’ and helping activists imagine how a ‘global perspective was planted in the youth at that time.’ Especially important to the student activists was the portrayal in the final novel, House of Glass, of the secret police agent who arrests Minke, the protagonist of the first three novels, and drags him off to the Moluccas. The Quartet’s depiction of the fissures that could weaken democratic movements showed the activists that they needed to band together in a broader coalition. This was vital in the months leading to the birth of a new party, the Indonesian Democratic Party, or PRD, Sudjatmiko recalled in a 2022 interview. They would often visit Pramoedya at his house, where they spoke with him about Indonesian historical events before and after independence. ‘We discussed history, war, culture—and it influenced our oratory.’ They even took quotes directly from his books.

Of course, some, like Minke, wouldn’t live to see the fruit of their labor. Thukul was disappeared by the regime as it clung desperately to power. With Suharto’s fall in 1998, the Quartet’s significance only grew, even as the ban continued in Indonesia. As Pramoedya struggled to write through his trauma, editing his prison memoir in the mid-1990s, he was simultaneously besieged by a throng of admirers from around the world, including Swedish embassy staffers (whose presence fuelled rumours of further Nobel Prize nominations).

In 1999, his memoir was published in English as The Mute’s Soliloquy, Pramoedya was finally free to travel to the United States for a book tour. He arrived at New Jersey’s Newark airport wearing a baseball cap, with his wife beside him, and irritable, as his trip overlapped with a short-lived attempt to quit smoking. While in the Empire State, he appeared at the Asia Society and walked out of a performance of Handel’s opera Giulio Cesare at the Met. His trip coincided with a New York Times review of The Mute’s Soliloquy by Jonathan Rosen, who praised Pramoedya as ‘remarkable for his ability to give brutal realism a mythic dimension.’

Returning to Indonesia, he joined a new political party, the People’s Democratic Party, founded in anticipation of Suharto’s fall, with the purpose of rebuilding Indonesia’s democracy from scratch. But publicly, he deferred to the judgments of the younger generation who’d founded the party, indicating that his membership was largely symbolic. When pressured to write about his own era—the Quartet ends in the 1920s, when Pramoedya was born, 100 years ago this year—he told friends that the present moment could not yet be expressed as literature. Perhaps he was baffled by the present, which encompassed his confusing release, his house arrest, the fall and aftermath of the dictatorship. The prehistory could be carefully studied and written out much more convincingly than the stifling present.

In early 2006, at eighty-one, he died at home from diabetes and heart disease, smoking clove cigarettes until his final breath. To his muted contentment, he lived to see the Quartet’s ban rescinded and Sukarno’s daughter Megawati elected president. This Earth of Mankind, the first of four films adapted from the Quartet, was released in Indonesia in late 2019. Pramoedya’s daughter Astuti was there with his grandchildren to celebrate a film that had been born as oral stories on a jungle porch, when he was disallowed from possessing pen or paper, then written down and smuggled out of a labor camp. Still, Americans and perhaps younger Indonesians watching the film on Netflix may remain unaware of what its author had to do to ensure its release. In an interview the year before he died, Pramoedya acknowledged that the United States had played a role not only in Indonesia’s coup and thus in the murder of possibly millions of innocent people, but also in his own cruel imprisonment. And yet in other late interviews—between bouts of bitterness—he admitted that, in the end, prison had fostered his writing; and that between forced labor, hardship, and confinement, he ‘considered all the oppression to be a game. And I took the challenge.’

Joel Whitney is an author and editor. His books include Finks: How the CIA Tricked the World’s Best Writers, and Flights: Radicals on the Run. He is the recipient of the PEN/Nora Magid Award for Magazine Editing for his work as a founding editor of Guernica, as well as the Discovery/The Nation Joan Leiman Jacobson Poetry Prize of the Unterberg Poetry Center. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Baffler, the Boston Review, Dissent, and Jacobin, among other outlets.

This is an extract of the essay ‘The Making of the Buru Quartet’ originally published in The Believer. Inside Indonesia thanks the magazine and Joel for their permission to publish this extract here.

The Believer magazine has just published its 150th issue! Subscribe today to receive this special anniversary issue: thebeliever.net/