The range and scale of events to celebrate Pramoedya’s 100th anniversary indicate that an important social and cultural phenomenon is underway

Max Lane

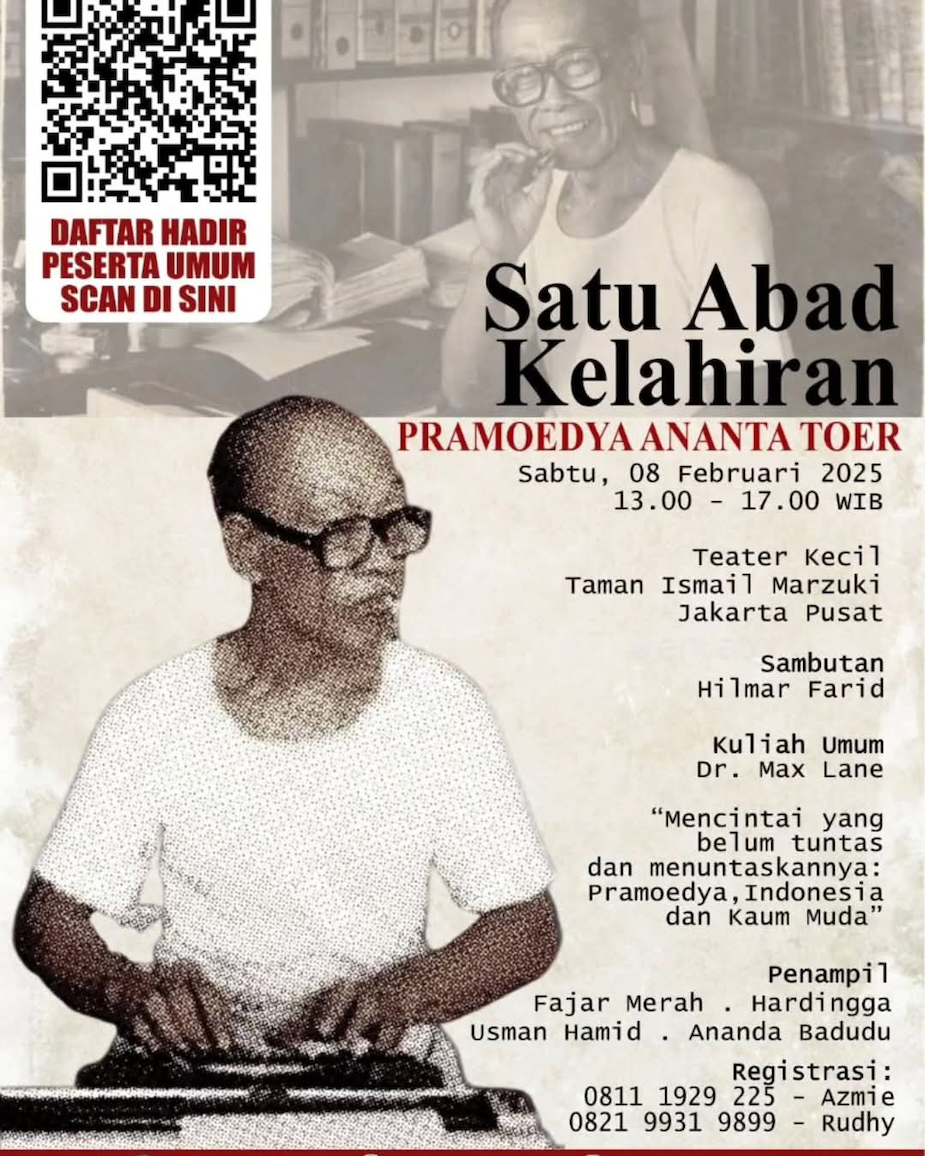

It was good to see the Teater Kecil so packed. Standing room only, so at least 400 people and a couple of hundred more outside. I later learned probably 5000 people watched the event on YouTube or on one of the sponsoring organisations’ social media streams. In fact, bookings for the event had filled up within a few hours of the publicity going online. There was no doubt that one of the bigger venues at Taman Ismail Marzuki, even with a 1,000 seats capacity, would have been filled.

The event was a series of talks to commemorate the centenary of the birth of Pramoedya Ananta Toer. This event at TIM was jointly organised by nine different organisations. They included trade unions, urban poor organisations, and student groups. The bookings had filled up so quickly, these organisations had to limit the number of their own members who could attend. They were the ones watching outside in the lobby on big TV monitors.

I was there as one of the speakers. Others who spoke that afternoon were Dika Muhammad from the Indonesian People’s Union of Struggle (Serikat Perjuanan Rakyat Indonesia, SPRI) and Sunarno the President of the Indonesian Trade Union Congress Alliance (Kongres Aliansi Serikat Buruh Indonesia, KASBI). Hilmar Farid, who had written his PhD on Pramoedya, spoke via video from Blora, Pramoedya's hometown, where a kind of Pramoedya Festival was being held. There was also a panel discussion with Roy Murtadho, chairperson of the Indonesian Green Party and Anwar Sastro from the Confederation of the Indonesian People's Movement (Konfederasi Pergerakan Rakyat Indonesia, KPRI).

Of course, the speakers were all in awe of Pramoedya’s literary and political achievements. Dika Muhammad, who gave a comprehensive speech at one point summed up the sentiment on stage and in the theatre:

Pram’s fictional characters are rebels. Arok, Wiragaleng, Minke, Hardo, Sama'an to Gadis Pantai are rebellious types. They are fighting for ideas and ideals. Many of them were defeated. Struggle does not always mean victory, but acting to realise ideals.

Dika, a leader of an urban poor organisation, continued:

I was impressed with Di Tepi Kali Bekasi. In the novel, the urban poor are elevated as the backbone of the Republic's power against Dutch Military Aggression. This epic is referred to by Pramoedya as the Revolution of the Spirit, from the spirit of colonisation to the spirit of freedom.

For myself, Dika’s was the most impressive speech, and without doubt captured the mood among the hundreds present, and also the thousands who watched online.

This event held on 8 February in Jakarta had a distinctly political character. The organisers were some of the major civil society and activist organisations in Indonesia. KASBI, with over 100,000 members, is the biggest of the trade unions not connected to any faction in the political elite. Their leaders had all read Pramoedya. This emanated so strongly from Dika’s speech, in particular.

This was probably the biggest event in Jakarta held close to Pramoedya’s birthday on 6 February. The Pramoedya Ananta Toer Foundation, established by members of Pramoedya’s family, and working with literary studies figures like Hilmar Farid, Berto Tukan and Martin Suradjaya, among others had decided to organise a major event not in Jakarta, but in Blora. The Indonesian Minister for Culture, Fadli Zon, who is more ideologically aligned with Pramoedya’s historical opponents, also made a speech. The local bupati had agreed to rename a main street Jalan Pramoedya Ananta Toer, but this was postponed after some protesters from the anti-Left Pemuda Pancasila protested the renaming.

Action

The event I spoke at in Jakarta reverberated with love of Pramoedya. And everything I heard about the events in Blora affirmed the same sentiment. What impressed me most, however, was the breadth of activity emerging from what I call the ‘dunia literasi’. Over the last 20 years there has been a multiplication of communal and activist libraries, book clubs and reading groups, and independent book shops. These are in many places across the country, including down at the district level.

When these groups use the word ‘literasi’, they are not referring to being able to read and write, but being able to read, comprehend, debate and appreciate literature. I don’t know if there has been any systematic discussion of this phenomenon. It is hard to judge its size, but it is clearly very substantial. In a country of 270 million people, of course, it no doubt affects a tiny proportion of people and can’t make up for literature not being studied in Indonesian high schools. The energy, it emanates, however, indicates it is the start of something that is likely to grow.

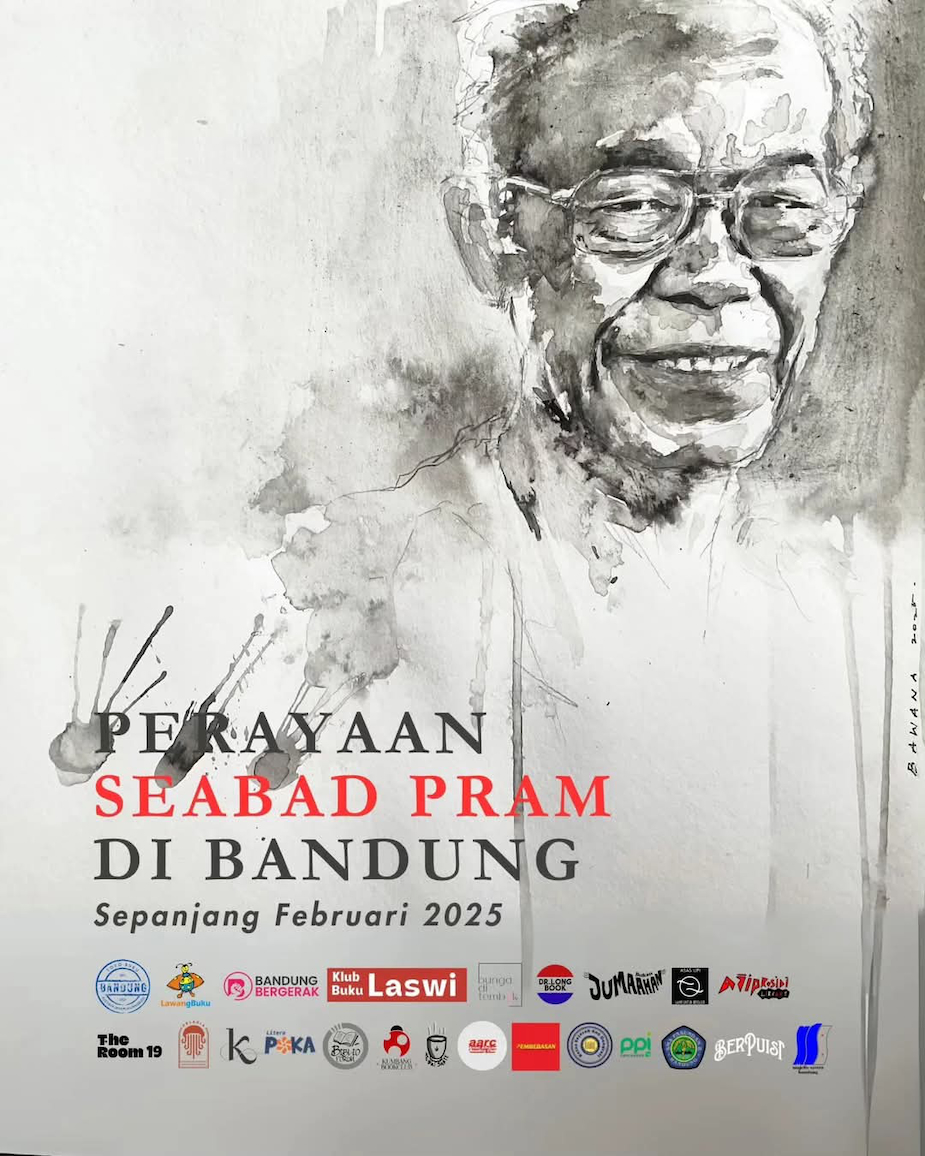

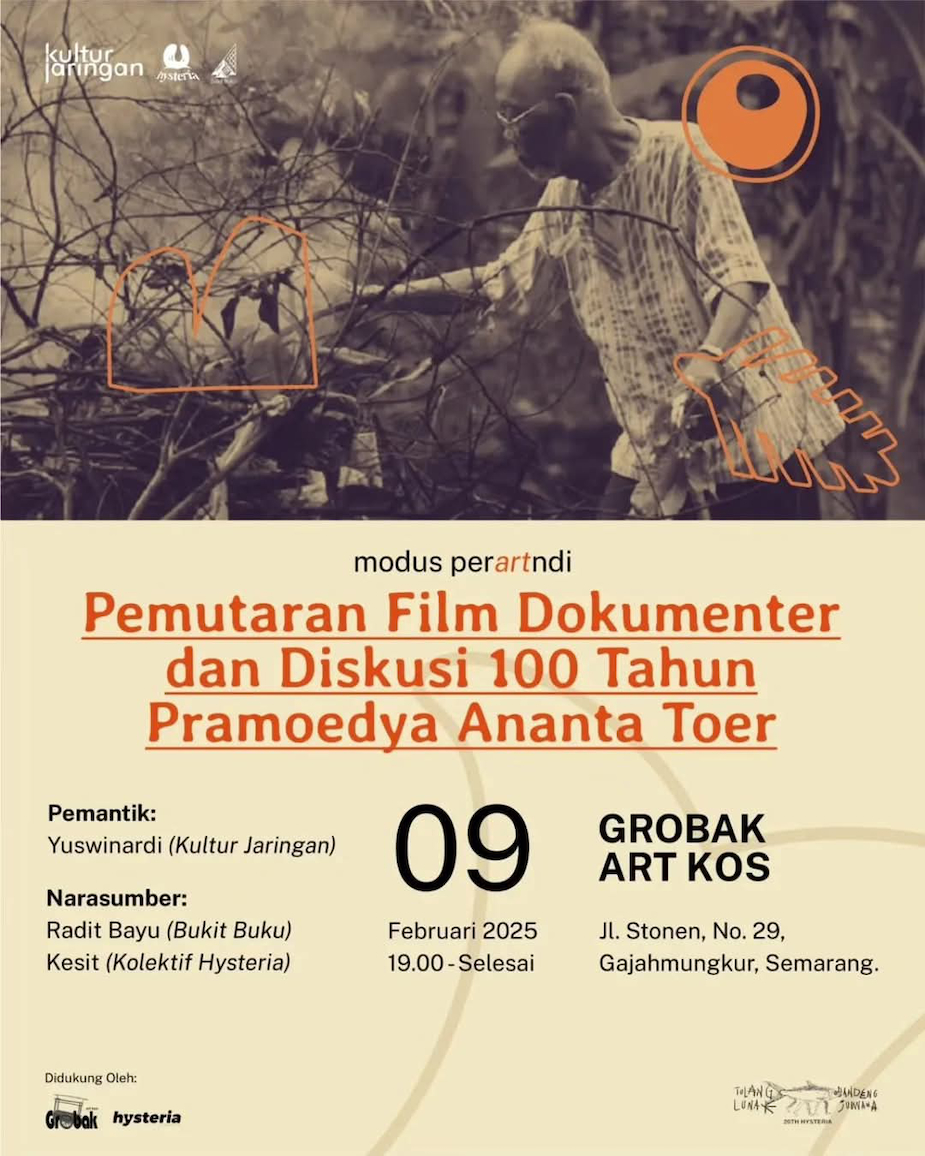

The energy was certainly evident in all the events organised to discuss and commemorate Pram and his writings. I counted scores of posters on my social media, and I am not even very present on platforms like Instagram, or Twitter or TikTok, where I am sure there were more. There were events in towns on every island of Indonesia: in provincial capitals as well as small towns. During February and March I watched as another and then another poster flashed up on my social media feed.

The activities will continue throughout the year. I spoke again via zoom from Melbourne at the program organised by the Teras Merah held at the Balai Budaya in Menteng. As well as talks and discussions they organised a fine arts exhibition to commemorate Pram; choosing to coincide these events with the anniversary of the date of his death, 30 April. There are also rumours of a conference on Pramoedya to be held later this year, but I have not yet seen confirmation.

Energy

In my view, this dunia literasi and also political activist celebration of Pramoedya needs to be noted as an indication of an important social and cultural phenomenon. There was no serious support for any of these activities from the government or even universities. The scores of events all came from within society, with no official encouragement. Where else do we see that? Certainly not in Australia.

No: Pramoedya’s works speak to a longing latent in Indonesian society. In his essay, ‘Pramoedya dan Modernisme Dunia Ketiga’, Martin Suryajaya writes:

That is why, when the generation that became the youth under the New Order first read This Earth of Mankind, they felt like they were breathing air from another planet. The Indonesia they read about there is so different from the Indonesia they see day to day.

And it is indeed very exciting and exhilarating – Indonesia just at the very beginning of its creation and full of the energy of creation.

In April, social media was hit by massive viral commentary and protests with two themes ‘Indonesia Gelap’ (Dark Indonesia) and ‘Kabur Aja Dulu!’ (Let’s Get Out of Here!). Both were cries of desperation about the corruption and shallowness of Indonesia’s political elite and the state of the country: the Indonesia the generations since 1965 see day-to-day. Pramoedya’s works, especially his historical novels, as Dika Muhammad emphasised at Teater Kecil, told of the energy of rebellion. Bumi Manusia showed how the very coming-into-being of Indonesia, was driven by that energy.

No one book or writer can change a whole country or set in motion fundamental transformations, but there is little doubt in my mind that those in Indonesia, especially young people today who love Pram’s novels, are affected by the potential for social transformation that his works show. While literature is not studied seriously, if at all, in Indonesian public schools, his works, and others, will be discovered in society gradually and haphazardly through the agency of the ‘dunia literasi’. There may still be a long way to go but the indications are there. If we look at the Goodreads data for book sales, Bumi Manusia is way ahead, even of the pop literature of Andrea Hirata and Teri Liye.

While it is that creative energy of rebellion which inspires people to commemorate Pramoedya, we must note, of course, that they are dynamic reads. I am never sure when I read Bumi Manusia and its sequels, but especially Bumi Manusia, whether I am actually watching a novel or reading a film. For Pramoedya reality is motion, not a snapshot, and he captures that motion so enthrallingly. Such is the power of story.

Max Lane is Senior Visiting Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, author of Indonesia Out of Exile: How Pramoedya’s Buru Quartet Killed a Dictatorship, (Penguin, 2023) and translator of Pramoedya’s Buru Quarter for Penguin Books.