Stories from East Nusa Tenggara

The state’s neglect of voices from below—such as what we see today, with central government elites ignoring the people’s voices whilst students and communities confront security forces on the streets—is nothing new in Indonesia. The New Order government’s (1966–1998) singular narrative about the violence of 1965 is one example of the silencing of the people’s voices, especially those of victims and survivors. For decades, the history of 1965 has been told and written by the victors to support the authorities in power.

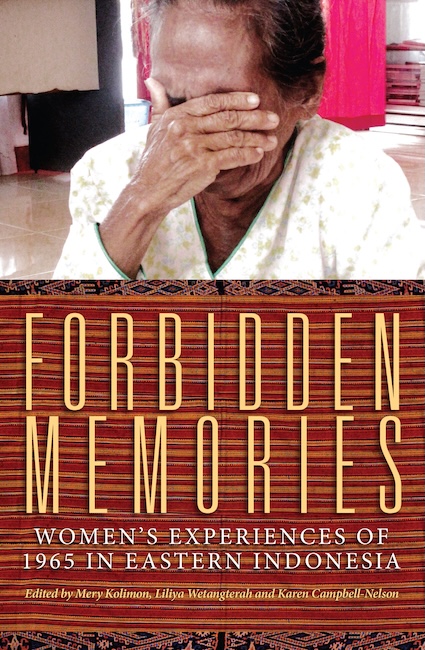

The Indonesian people have been forced to believe the rulers’ version of what happened during those violent events. The film The Treachery of G30S/PKI, screened annually and made mandatory viewing for schoolchildren, legitimised the annihilation of members and sympathisers of the Indonesian Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia, PKI) as well as the repression of Gerwani members (Gerakan Wanita Indonesia, a women’s organisation associated with the PKI). In official historical records, the PKI was branded the nation’s villain, and Gerwani members were portrayed as seductive women who mutilated the generals at Lubang Buaya. This version of history became the justification for punishing them without due process and for destroying women’s political institutions and movements. For 32 years under the New Order, the people were fed lies about what had truly happened. In such state-authored histories, the voices of victims were silenced and demonised. Their memories of these events remain forbidden memories.

In opposition to this singular narrative supported by the Indonesian government is the writing of 1965’s history by civil society, a process of writing ‘history from below’. As historian David Hitchcock (2004) explains, ‘history from below’ is an approach that seeks to make ordinary people its subjects, focusing on their perspectives and experiences, in contrast to the traditional political histories centered on ruling elites. This process aims to preserve and foreground the voices and experiences of those marginalised and unable to record their own stories. Initiatives to write history from below have taken place in various regions across Indonesia, including in East Nusa Tenggara (Nusa Tenggara Timur, NTT).

Creating counternarratives in East Nusa Tenggara

Since 2010, a group of researchers and activists from the Eastern Indonesian Women’s Network (Jaringan Perempuan Indonesian Timur, JPIT) for the Study of Women, Religion, and Culture has been gathering narratives and documents from victims, survivors, eyewitnesses, and their families. Particular focus has been placed on the voices of women survivors. Beyond the fact that the violence of 1965 remains a highly sensitive issue, the motivation behind this research was twofold: first, the redress the absence of in-depth studies on the subject in the region, and second, to address the need to develop a contextual theology rooted in the social and cultural struggles of local congregations—one that could help drive church reform in this predominantly Christian area. The findings of this research were published in the book Memori-Memori Terlarang (2012), later translated and published as Forbidden Memories (2015).

My involvement as a member of the research team and co-author of the book marked the starting point of my ongoing work to support victims and survivors. Beyond research and publications, the network has remained steadfast in its advocacy and support for survivors, including: pastoral care through the Sahabat Doa Lansia (Prayer Companions for the Elderly) program, held every two months; economic empowerment initiatives such as weaving and livestock projects; assistance in accessing services from the National Human Rights Commission (Komnas HAM) and the Witness and Victim Protection Agency (LPSK), and basic services from the local government; and connecting survivors with journalists, researchers, documentary filmmakers, and others who can amplify their voices more widely.

Following President Joko Widodo’s issuance of Presidential Instruction No. 2 of 2023 on the non-judicial resolution of 12 cases of gross human rights violations—including the 1965 case—JPIT seized the moment to push for the memorialisation efforts sought by survivor communities. At the end of 2024, after a participatory dialogue process between survivor communities, civil society, churches, and government representatives, a memorial monument was erected at a mass grave site in East Kupang. This site was where 18 people accused of being PKI members were executed by the military, with assistance from local civilians, on 6 February 1966.

The memorial stands as part of a broader recovery process for survivors and their families, while also serving as a symbol of recognition by both the state and society of the gross human rights violations committed in 1965–1966. The establishment of this memorial at the mass grave site is also intended to foster public education for the younger generation, so that knowledge and understanding of the 1965 atrocities can be preserved, and so that such violence will not be repeated in the future.

Gathering stories in NTT

During the course of my research and advocacy work, I became increasingly aware of the need to preserve all research findings and historical documents that had been collected, so they could be accessed safely and more widely by the public in the future. As a result, in early 2024, I joined the Indonesia Trauma Testimony Project (ITTP), which seeks to offer a new understanding of Indonesia’s history, including the involvement of civilians in the country’s most critical and bloody turning point: the mass killings of 1965–1966. The project also aims to collect documents and archives for the writing of Indonesian history. In a context where history in Indonesia has often been distorted to serve those in power, the question of truth becomes crucial: What really happened?

This project is vital because it arises from concern over the ‘memory sickness’ that the nation will continue to suffer if there is no courage to investigate and listen to the experiences of victims, leaving only a dark void in Indonesia’s history. Everyone involved in collecting and archiving these testimonies believes that history is one of the greatest teachers: humanity can learn from the good that civilisations have achieved in the past and from the wrongs that must be addressed so that we might all become wiser in the future. We do not intend to claim that the victims’ voices are the only or absolute truth. However, listening to those who have long been silenced provides a broader and more honest picture of what truly occurred during one of the darkest periods in the nation’s history.

As a field researcher, my main tasks involve meeting with the owners of community archives (and those who have inherited those archives), interviewing victims, survivors, eyewitnesses, and perpetrators, and collecting historical materials at risk of being damaged or lost. Most of the people I meet are women victims and survivors whose stories were previously documented in the book Memori-Memori Terlarang between 2010 and 2012. However, I also meet male survivors and victims, as well as eyewitnesses. For me, this work is part of writing history from below, dedicating oneself to listening to the voices of those who have been ignored by the state for decades.

Collecting stories about the events of 1965 is not easy. Many victims, survivors, perpetrators, and eyewitnesses who were directly involved have already passed away. Those who are still alive are often very elderly. Asking them to recount their memories of the violence they or their loved ones experienced requires emotional preparedness and courage—both on their part and on mine as the interviewer. Documents related to the 1965 events are also difficult to find, as many were destroyed by participants for fear of potential scrutiny by the authorities. Furthermore, the research area—spread across multiple islands—demands careful planning before going into the field. To date, I have traveled to four locations across the islands of Timor, Sabu, Alor, and Flores to meet and interview research participants.

Revisiting the past is extremely difficult and traumatic for many people, especially victims who have never received advocacy before. That period has become a forbidden memory in Indonesian history, suppressed deep within the memories of victims and their communities. In fact, all segments of the nation were affected by the 1965 events, whether as victims, family members of victims—including their descendants—, perpetrators, or communities misled by the narrative of the time. We tend to think that peace will come if we simply avoid discussing the past. Yet in doing so, we can never truly come to terms with ourselves; the ghosts of the past will continue to haunt us. That is why, difficult as it may be, we must undertake the work of healing this collective trauma. One crucial path is through a process of truth-telling that gives space for the voices and experiences of victims and survivors. From my experience in collecting these stories, I have learned that this is the price we must pay if the nation hopes to move forward, instead of being perpetually shadowed by its past. The healing of this collective trauma can only happen if the nation dares to speak again about what truly occurred.

Writing history as grassroots theology

As someone studying theology and in training to become a pastor in the Evangelical Christian Church in Timor (Gereja Masehi Injili di Timor), my involvement in efforts to listen to history from grassroots communities represents a theology-from-below approach. Unlike theology-from-above, which places divine revelation as the dominant source, theology-from-below begins with human experiences and conditions—especially those of the oppressed and marginalised—to articulate the meaning of faith.

Theology and politics are inevitably intertwined. A faith community’s reflection on the Divine as Creator and Sustainer shapes how that community organises life together in society. Politics, at its core, is about structuring a community for the welfare of all its members. When politics no longer serves the noble goals of justice and the well-being of all citizens, and instead becomes a tool of oppression against the people, then religious language about God, humanity, and the world must respond to this distortion. Religions that claim truth, love, justice, and equality as their core values should be at the forefront in opposing injustice and human rights violations. My experiences meeting and interviewing dozens of people across five regions of East Nusa Tenggara (Kupang City, East Kupang, Sabu, Alor, and Sikka) and visiting several mass grave sites have strengthened my conviction about the importance of amplifying the voices of those ignored by the state in the process of building a civilised and just nation.

Martha Bire is a researcher, writer, and advocate for victims of human rights’ violations from East Nusa Tenggara (NTT). She is currently serving as a vicar (pastor-in-training) in the Evangelical Christian Church in Timor (GMIT).