Preserving memory, strengthening counter-narratives and building solidarity

The process of democratisation that followed Suharto’s resignation extended into the realm of history. His fall marked the beginning of a freer and more open engagement with the past, breaking away from the rigid, state-controlled narrative of historical truth imposed during the New Order regime. A key part of this shift involved challenging the official account of the September 30th Movement (G30S), which had blamed the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) for being ‘mastermind’ (dalang) behind the coup. This distorted narrative served as a justification for the military—particularly the Army and Suharto—to carry out a political genocide, targeting PKI members, leftist groups, and supporters of Sukarno. This political genocide was one of the most grievous crimes in Indonesia’s history and has long been obscured from the nation’s memory and historical record by the state’s authorities. That is why, in 2016, I decided to establish the 1965-1966 Online Genocide Library (Perpustakaan Online Genosida/ POG 1965-1966), to document the wide range of literature related to the 1965-1966 political genocide, as part of an effort to expand democratic space and uncover historical truth.

Turning the tide of Indonesian history

The 1965 survivors’ community has long been engaged in efforts to document the history of 1965. After the 1998 reform, 1965 survivors Sulami Dodjoprawiro, Hasan Raid, and Pramoedya Ananta Toer established the Foundation for Research of the Victims of the 1965 Killings (YPKP 1965) on 19 April 1999. Not long after, branches of the YPKP 1965 were also established in various regions. The YPKP 1965 launched the first edition of the organisation’s bulletin, Soera Kita (Our Voice), in November 1999 and, significantly, in November 2000, excavated a mass grave in Ndempes Forest, Situkup Village, Kaliwiro, Wonosobo, Central Java.

Meanwhile, in 2000, a group of young Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) activists led by Imam Aziz founded Syarikat Indonesia. Syarikat Indonesia sought to build reconciliation between former 1965 political prisoners and perpetrators of violence at the grassroots level. This form of deep reconciliation was not merely about mutual forgiveness and handshakes but was founded on efforts to uncover the truth.

That same year, a group of historians and activists launched an oral history project, interviewing hundreds of victims of the 1965–1966 events across Java, Bali, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Sumatra. This initiative was set up under the Indonesian Social History Institute (ISSI) in 2003. In 2004 the oral interviews were then examined and published in the book Tahun Yang Tak Pernah terakhir (The Year That Never Ended).

Although efforts to uncover the truth and disseminate counter-narratives to the official history have multiplied, these initiatives continue to face risks and repression, both from state apparatuses and mass organisations whose repressive actions are tolerated by the government. Accusations that these truth-telling efforts are attempting to revive communism or are ‘New Style Communism’ and so forth, are still used to stigmatise and intimidate the public, becoming effective tools to persecute initiatives aimed at historical disclosure. This is supported by the Decree of the Provisional People's Consultative Assembly Law Number XXV/MPRS/1966 concerning the Dissolution of the Indonesian Communist Party, which remains in effect, along with its derivative regulations, which are still highly effective as anti-communist propaganda against anyone considered critical or oppositional to the government.

Recently, the Indonesian government, through the Ministry of Culture, has also undertaken systematic and institutionalised efforts to rewrite history from a perspective favorable to those in power, glorifying those whose hands are stained with blood from the past, including the period of the 1965 genocide.

The 1965-1966 Online Genocide Library

When I began developing the POG 1965-1966, a substantial and diverse body of literature on the 1965-1966 events was already available both offline and online. This extensive literature provides a clear account of the grave and extraordinary crimes that form part of Indonesia’s history. It must be acknowledged, however, that many aspects remain undisclosed. Much still needs to be studied and explored; the majority of eyewitnesses have passed away, the killings spanned almost the entire country with many regionally-specific dynamics, and many state archives remain hidden.

The collection at the Netherlands Royal Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV)—the world’s largest library collection on Indonesia—in Leiden, demonstrates the rapid growth of literature on the 1965-1966 violence. In 2013, Gerry van Klinken noted in a presentation, ‘An Indonesian Debate: Some “Landmines” in the KITLV Archives,’ that there were 1,939 collections worldwide referencing communism in Indonesia and the 1965 violence. Of these, 1,370 originated from Indonesia, and 766 were published after Suharto’s fall. This literature includes autobiographies, novels, books, films, audio recordings, magazine and newspaper articles, and television documentaries.

Within the POG 1965-1966, I have recorded more than 97 published memoirs, biographies and autobiographies of 1965 survivors—both exiles and former political prisoners in Indonesia. This count does not include anthologies of survivors’ testimonies, interview videos, documentary films, and articles by writers and journalists featuring memoirs or brief life stories of the 1965 survivors. Additionally, there is an abundance of unpublished oral history interviews from 1965 survivors.

POG 1965-1966 is a repository hub for literature available online. Rather than attempting to physically store thousands of books, dissertations, theses, academic papers, opinion pieces, news articles, and other literary materials; rather, I compile and connect readers to those publications online.

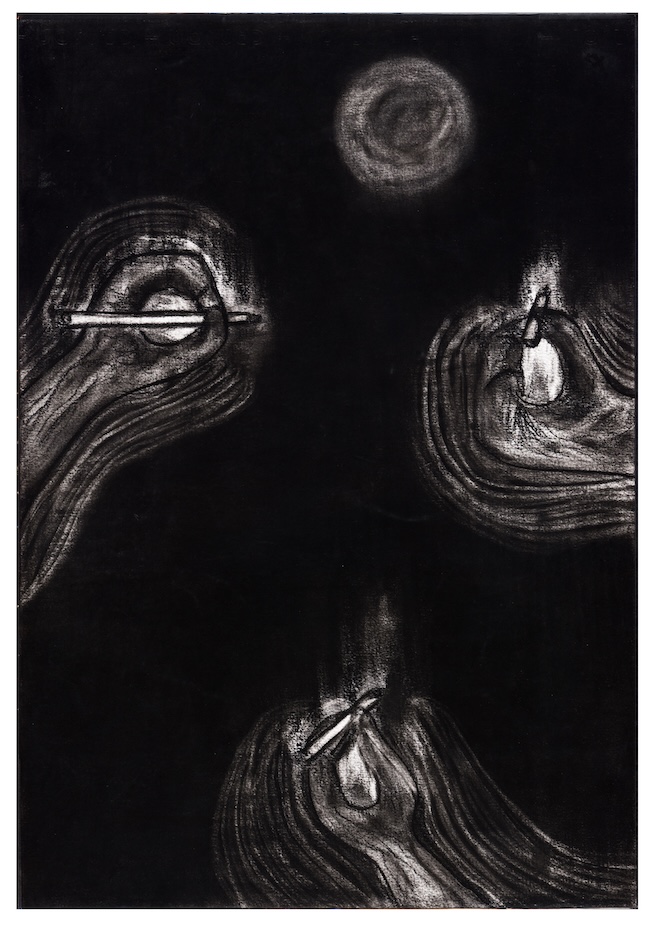

In cases where important publications are not available online, I document all reviews, recorded book discussions, and media coverage of these books. For example, regarding the 97 published memoirs mentioned earlier, I have gathered various literature discussing the stories of the respective survivors. The POG 1965-1966 plans to compile an annotated bibliography of published books, including memoirs, biographies/autobiographies, and scholarly studies. This is the only site that also documents hundreds of artworks by dozens of Indonesian artists relating to 1965. The Library also has collections of films/videos.

To enrich our understanding of the events in Indonesia, I have expanded the Library’s scope to include crimes against humanity and genocide in other countries, as well as other crimes against humanity perpetrated throughout the remainder of the authoritarian/fascist New Order Suharto regime and successive administrations.

I also believe that to develop a full understanding the 1965-1966 genocide, we must understand the dynamics of Indonesian history, especially the history of the Indonesian leftist movement, which has long been erased and manipulated by successive regimes and those in power. The online library also includes documentation of the history of leftist movement in Indonesia.

Preserving and building

The process of democratising history continues despite setbacks in reforms related to the rule of law, the eradication of corruption, collusion, and nepotism (Korupsi, Kolusi, Nepotisme, KKN), the abolition of the Dual Function of the Armed Forces (ABRI/TNI-Polri), the enforcement of human rights (HAM), and the implementation of regional autonomy.

The democratisation of Indonesia’s history has been able to proceed relatively unimpeded—particularly in today’s digital era, which enables freedom of information through the emergence of new media. These new media platforms provide open spaces to build counter-narratives, shape collective memory, and foster an interactive culture that transcends the boundaries of space and time.

At the same time, a new generation has emerged—growing up in a cosmopolitan atmosphere, more open, and free from the fears of the past. However, it must also be acknowledged that these new media have also become a platform for reactionary groups, anti-communists, and defenders of the ‘state-sanctioned version of history’ inherited from the New Order regime. While official history still dominates and past atrocities are often denied, the power of these narratives is gradually waning.

The POG 1965–1966 was born from the momentum of the digital era, coinciding with increased public access to a wide array of reading materials that are no longer confined to physical collections in conventional libraries. Nevertheless, the greatest challenge lies in how to draw the younger generation’s interest in their nation’s history—a history that, whether consciously or not, plays a role in shaping both the present and the future. This is particularly important given that the formal education system remains constrained by a curriculum that adheres to manipulative official historical narratives.

The POG 1965–1966’s main strength lies in its promotion of diverse sources and literary formats. This diversity aims to open as many access points to the public as possible. For instance, low reading interest can be bridged through alternative forms of expression such as paintings, music, novels, podcasts, discussions, journalistic articles, films, photo features, or popular writings that convey personal stories and family memories in a more intimate and engaging way.

In terms of knowledge production, these sources come from a wide range of people: survivors (across three generations), academics, writers, religious figures, activists, artists, journalists, and everyday citizens. The POG 1965–1966 stresses the importance of combining counter-narratives grounded in archival and scholarly research (macro-history) with the moving testimonies and personal memories of survivors (micro-history). In terms of its scholarly approach, the POG 1965–1966 serves as a meeting ground for interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary studies, encompassing comparative genocide studies, transitional justice, memory and heritage studies, history, politics, anthropology, psychology, gender, culture, and law.

Ultimately, the POG 1965–1966 hopes to contribute to building and strengthening a culture of critical thinking and historical awareness, nurturing collective memory, expanding the reach of counter-narratives, and fostering solidarity that arises from knowledge, understanding, sympathy, and empathy.

Andreas Iswinarto has run the Online Genocide Library of 1965-1966 since 2016, is a member of the Association of the International People’s Tribunal for 1965 (IPT 1965) and is active in the Beranda Rakyat Garuda discussion group.