Book review: Blood and silence

09 February 2026by DUNCAN GRAHAM

Dreams of scale

09 February 2026by ATMAEZER HARIARA SIMANJUNTAK

Photo essay: Negotiated tolerance

27 January 2026by PUTU ANGITA GAYATRI & AHMAD YUSRIFAN AMRULLAH

Roots of ecological disaster

02 January 2026by KHALID SYAIFULLAH & WARDATUL ADAWIAH

Essay: How an American teenager became a Sahabat NOAH

22 December 2025by AANIKA I.

Essay: Would you fall in love with a railway station?

18 December 2025by NOANDHA DHEGASKA

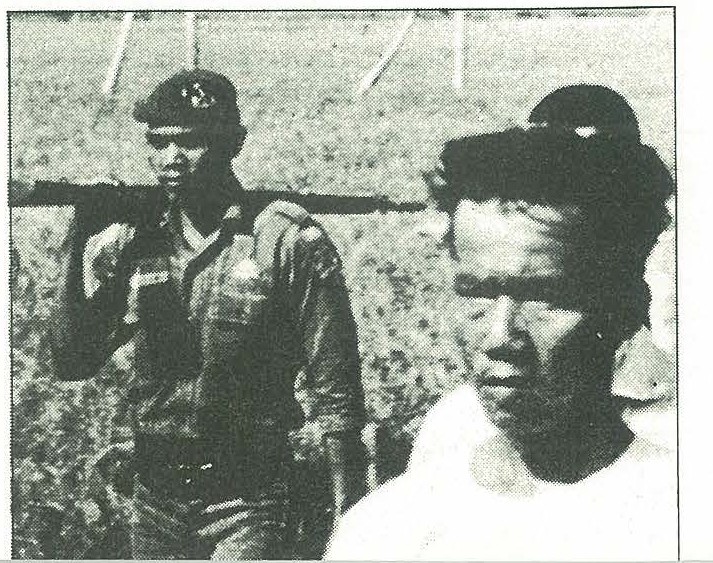

Review: The collective deradicalisation of Jemaah Islamiyah

16 December 2025by KHALIMATU NISA

Essay: Shelter, not display

04 December 2025by DANKER SCHAAREMAN

Essay: Tracing the social life of a keris

17 November 2025by JULIANA KÖNNING

Essay: The day after the death of Affan Kurniawan

07 November 2025by RAHMADI FAJAR HIMAWAN