How British propaganda tried to provoke a coup and encourage mass killings in 1965-66

One morning in early December 1965, Ross Taylor, an English engineer working and living in Pasuruan, East Java, went for a stroll. What he saw on his walk shocked him. Floating in the stream which ran beside his house were three headless corpses. A little upriver, he noticed half a dozen decapitated heads arranged along the wall of a small bridge, and just beyond that a group of children were helping a few lifeless bodies down the stream with bamboo poles.

What Taylor saw that day were just some of the victims of one of the worst instances of state-sponsored mass violence in human history. Between October 1965 and March 1966, the Indonesian army and a network of militia groups killed approximately half a million people and detained another million without trial. Some scholars have described the events as genocide.

Taylor would later provide this account of what he witnessed to embassy officials, including details of the number of people killed in his area, and observations about a local army commander he had seen with a list of targets. What he did not know was that the British government was in fact encouraging this violence through a covert propaganda campaign designed to denigrate the army’s principal target, the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI).

British propaganda exposed

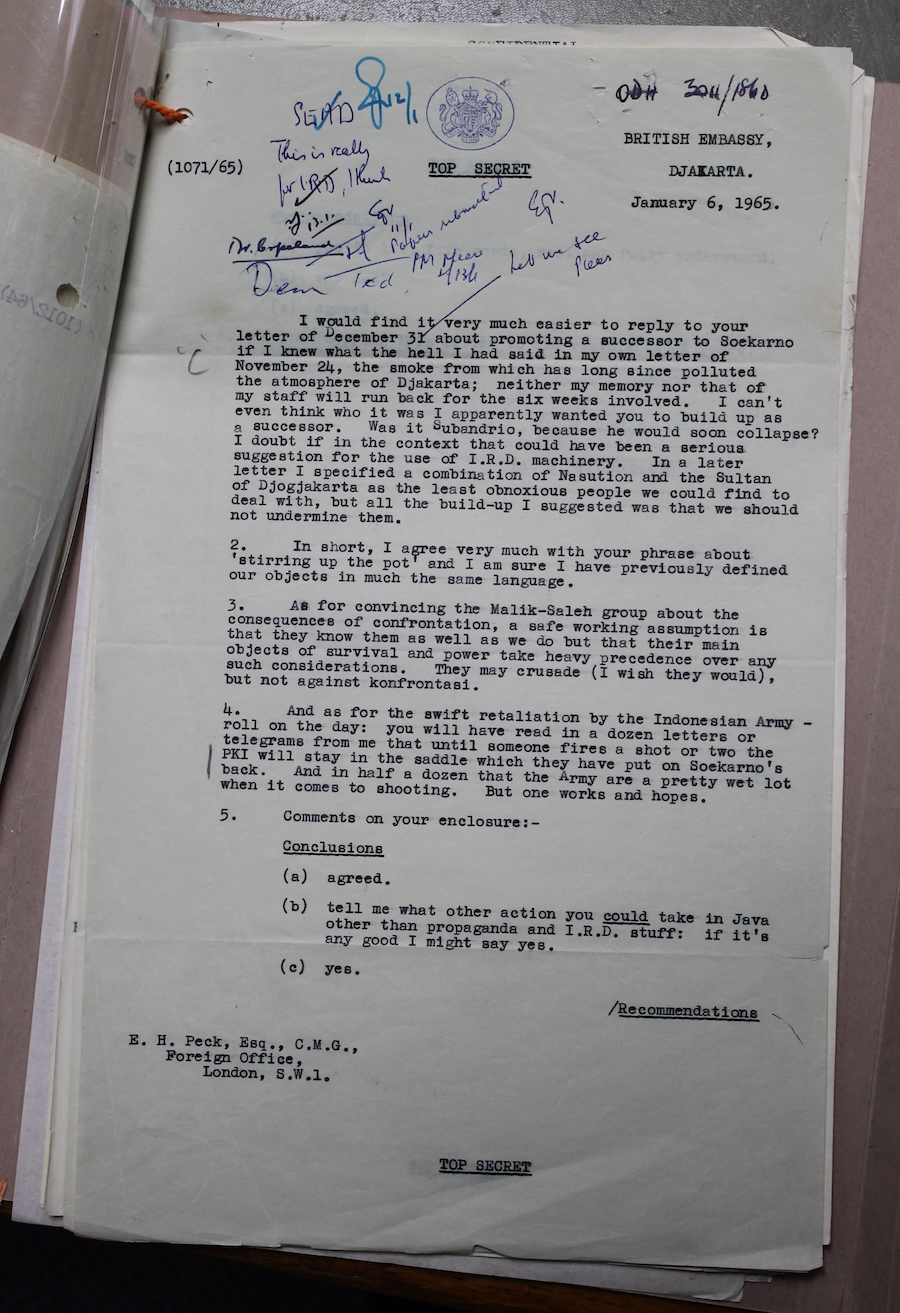

Britain’s propaganda operations in Indonesia remained a state secret until 1998, when journalists Paul Lashmar and James Oliver published Britain’s Secret Propaganda War. Based on interviews with former officials, they found that the British foreign office’s secret Cold War anti-communist publicity arm, the Information Research Department (IRD), had manipulated international media flowing into the country in an effort to influence Indonesian affairs.

Some years later historian David Easter drew on declassified government files to add a great deal to our understanding of this propaganda system, or what British intelligence officer Norman Reddaway called the ‘bludgeon’. IRD received information on events inside Indonesia from British overseas missions, before selectively passing it along to international news agencies, newspapers and radio broadcasters publishing material in Indonesia. Although Easter lacked access to the resulting media itself, he has argued that discussion about its content recorded in the diplomatic files prove that ‘Britain incited hostility to the communists and at least implicitly encouraged the mass murder of thousands of people’.

How British officials wished for the propaganda to work is clear from correspondence in the diplomatic files. They hoped it would provoke the PKI into a rash power grab, which would then justify a violent response by the army. In late December 1964 under-secretary to the foreign office, Edward Peck, wrote to the British ambassador to Indonesia, Andrew Gilchrist, that it was important to ‘do anything we can to help to create conditions likely to induce the PKI to show their hand prematurely and invite swift retaliation from the Indonesian Army’. In a letter to Gilchrist dated 25 January 1965, head of the Indonesia/Malaysia department at the foreign office, Anthony Golds, assured the ambassador that they will ‘certainly do what we can… to spark off a shooting war’. It was now just up to IRD’s output to bring all this about.

Project ‘stiletto’

What the British needed was a more precise propaganda instrument. In 2021, journalist Nicolas Gilby uncovered newly declassified files in the UK National Archives which detailed just this. First proposed by Gilchrist as early as March 1964, a small IRD sub-team based in Singapore was tasked with the creation of an unattributable Indonesian language newsletter. Reddaway, now conducting operations as ‘Political Warfare Coordinator’, nicknamed the project their ‘stiletto’.

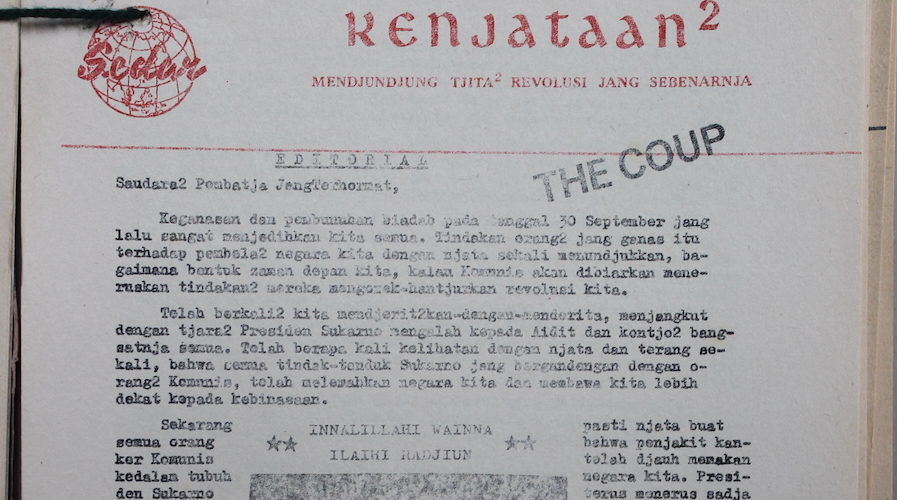

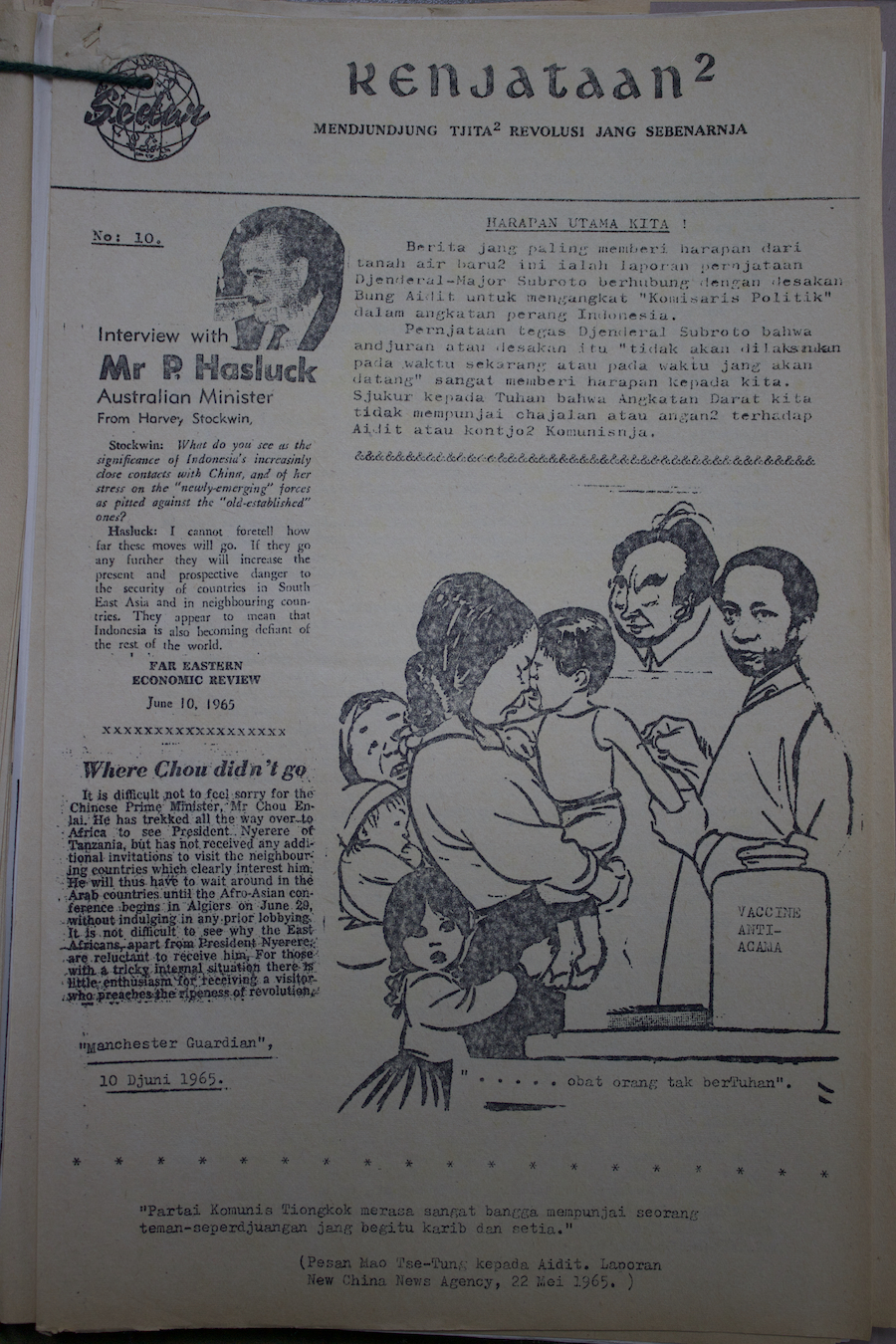

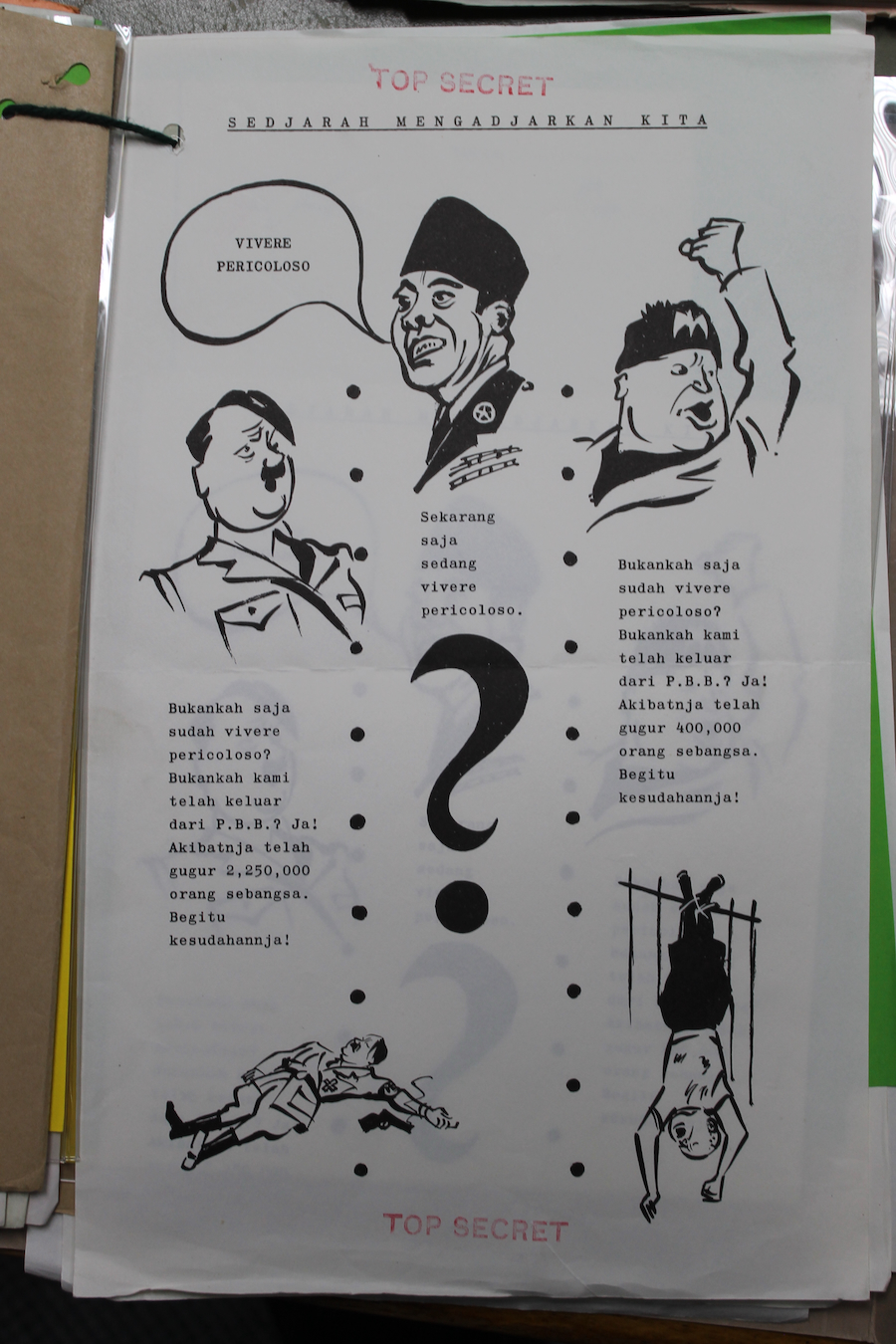

The newsletter was named Kenjataan2 (‘Facts’) and contained reportage, comment, and satirical cartoons on Indonesian current affairs by a group of fictitious regular contributors. The first copies of the newsletter were posted in April 1965, addressed to between 800 and 1500 ‘personages of influence’ in Indonesia, as well as handful of Indonesian diplomats in Europe. According to a later internal IRD report, the publication was even brought to the attention of Sukarno, although it is not known if he ever saw it, let alone read it. As to its content, it was not unlike a tabloid newspaper with virulently anti-Sukarno, anti-China and anti-Konfrontasi views – though its most inflammatory language was always reserved for the PKI.

Early on 1 October 1965 six of Indonesia’s highest-ranking generals, and an assistant, were abducted from their homes in Jakarta. All seven were killed and disposed of while two army battalions occupied key positions in the centre of the city. In radio statements, the group responsible for the actions announced that they had seized state power. As quickly as it had begun, however, the movement was put down by forces under the command of General Suharto, who had not been targeted. By 6:00 pm, he had total control of the city. Just a few days later he used the incident to justify a takeover of the entire Indonesian army. Suharto then blamed the failed coup on the PKI and gave orders for the slaughter of its members.

There is no evidence to suggest that the British had a hand in what happened on 1 October. In any case, they saw it as the perfect pretext for the army to move against the communist party. Less than two weeks after the coup, the new head of the Indonesia/Malaysia department at the foreign office, Henry Stanley, wrote: ‘We see every advantage in letting the generals get on with clobbering the communists’.

British strategy was not limited to letting the army ‘get on’ with the massacres. After a directive from London, IRD officials were set to work on Kenjataan2, and by mid-October a special edition of the newsletter had been written and published. In its provocative editorial it states: ‘Surely it must now be obvious to everybody that the cancer of communism has eaten far into the body of the state.’ It continues: ‘The evil must be eradicated, it must be extracted from the body of the State.’ According to the newsletter, the path forward was clear: ‘No, we do not cry out for violence, but we do demand in the name of all patriotic people that this Communist cancer be cut out of the body of the state. That actions be taken to ensure that never again, never again, shall these men of godless evil be allowed to raise their hand against the state’. In another article, the actions of Suharto’s army are praised: ‘Thanks to the loyalty of the army and leadership of its generals, the PKI is now a wounded snake. Now is the time to kill it before it has a chance to recover.’ It concludes: ‘PKI and all it stands for must be eliminated for all time’.

This kind of coverage continued throughout November, December, and into the new year, even as news of the horrors reached officials in Singapore and London. In early November, the editorial describes the PKI as ‘monsters’ and concludes: ‘Let us make sure that the PKI are never allowed to raise their heads again.’ Two weeks later, the newsletter features an article which argues that the ‘PKI and all Communist organisations must be eliminated, and if Sukarno is loath to do that, then the Army must do it on his behalf.’ Correspondence in the diplomatic files makes clear that by January 1966, British officials were certain that the killings were being conducted by either the army itself or other groups with the army’s support. That month the Kenjataan2 editorial stated that ‘the work started by the Army must be carried on and intensified’.

Decolonialisation and Britain’s Cold War

Following the discovery of these files, the way in which the British government attempted to influence events in Indonesia between 1963 and 1966 is clearer than ever. But what motivated them to do so, is not. David Easter argues it was a response to Konfrontasi, the Indonesian government’s diplomatic and military campaign to resist the British sponsored creation of Malaysia in 1963. The PKI supported the campaign and therefore the British wanted them gone. Nathaniel Mehr disagrees, contending that concerns over Konfrontasi were always secondary to the ‘overriding objective’ of preventing the formation of a communist Indonesia, whilst Christopher Tuck posits that the aims for the propaganda campaign changed over the course of October 1965, from ending Konfrontasi to mobilising opponents of communism to crush the PKI.

The newly declassified IRD files make it clear that the propaganda operations were articulated as a response to Konfrontasi in the short term and the rise of Indonesian communism in the long term. That is to say, British motivations lay at the nexus of colonial and Cold War policy objectives.

This duality of British motivations can be seen by charting how British strategy in Indonesia developed from 1945 onwards. After World War II, global politics were quickly gripped by the logic of the Cold War. In this context, Indonesia was viewed by British decision makers as crucial in the fight against communism in Asia. For example, British Commissioner General in Southeast Asia, Malcolm MacDonald, viewed the region in terms that later became known as the domino theory: once a large country like Indonesia fell to communism, the rest would follow. Britain also retained a large stake in Royal Dutch Shell, which owned 75 per cent of oil production facilities in Indonesia before the war, while the Straits of Malacca were considered vital as a route for warships. Put simply, Britain could not accept Indonesia falling into communist hands.

When the PKI had a series of impressive showings at local and national elections in 1957, the British embassy in Jakarta worried that ‘communist penetration’ was ‘serious and disturbing’, while an official in Singapore dispatched a telegram to the prime minister warning that a ‘Communist dictatorship’ was imminent. By 1962, the PKI claimed over two million members, making it the largest communist party outside the Soviet Union and China. Meanwhile, Indonesian president Sukarno had begun openly supporting communism at home and abroad. All this was grim reading back in London where, as a later foreign office report stated, British officials believed a communist Indonesia ‘would have world-wide repercussions highly damaging to western interests in general and to British interests in particular’.

It was also in 1962 when the Malayan and British prime ministers signed a formal agreement on the formation of the Federation of Malaysia. This new country would have strong links to Britain through various security and economic agreements and was seen in London as the best way to perpetuate influence in the region into the post-colonial era. By January 1963, however, the Indonesian government had come out against it in a policy coined Konfrontasi. In April that year, the Indonesian army began to conduct cross-border incursions into Malaysian territory in Borneo, where they clashed with British troops.

By 1963, Indonesia had become a major strategic headache for British decision makers. It seemed the country was hurtling toward communism and, to make matters worse, its government was now waging a low intensity war against British forces in the rainforests of Borneo. Reminiscent of how a certain British politician reacted to Egyptian president Abdul Nasser, frustrated officials in London warned that Sukarno was ‘a man with much of the instability and lust for power of Hitler.’ (In January 1965, comparisons of Sukarno to Hitler would bleed into propaganda output). Something needed to be done. But what?

Indonesian politics was as polarised as it had ever been. The British believed they could exploit this. If enough opposition against the president and the PKI could be generated, then communism in Indonesia would be put to bed and Konfrontasi brought to an end.

Unfortunately for Britain, the options available for intervention were limited. The British Treasury was facing serious balance of payments problems, blamed by the public and politicians alike on wasteful overseas military expenditure. In 1963, total defence expenditure was running at an unsustainable £1.7 billion a year, almost a tenth of the gross national product. Anything expensive, or overtly public, was off the table. Cue: the IRD. The department was tasked with running a low-cost and highly secretive propaganda campaign. By April 1963 operations had begun, and by end of 1964 the special sub-team based in Singapore was devoted to the mission and the publishing of Kenjataan2 once a fortnight on a budget of just £30,000 per year (later increased to £85,000).

If the timeline of British reaction to developments in Indonesia does not make its rationale clear, in February 1965 a memorandum laid it out in black and white. The short-term aim was getting Indonesia to cease its policy of Konfrontasi, while in the long-term Britain wanted a ‘non-communist and non-aligned Indonesia'. Cold War and colonial policy objectives were threatened simultaneously, and the propaganda campaign was a reaction to this. It is also with an appreciation of this duality in reasoning that the especially vicious condemnation of the PKI makes sense. They were perceived as uniquely antithetical to both strategic goals, and as a result they bore the brunt of the attacks in the propaganda output – even when their members were being slaughtered.

By mid-1966, the killings had largely stopped. Communism had been ruthlessly crushed and the new president Suharto had paused Konfrontasi. For the British it was time to pack up and go home. In June that year, Kenjataan2 ceased production, though radio propaganda continued until August. The Singapore team was dissolved and its staff redeployed. British covert propaganda operations in Indonesia came to an end. According to the British, the missions had been accomplished. Unfortunately for the Indonesian people, this came at a truly brutal cost.

Aidan Hall (aidan.hall10@outlook.com) holds an MSc in International History from the London School of Economics and writes about Indonesian history and politics.

Note on archival sources: For the recently declassified originals of the newsletter, Report on operations by the South East Asia Monitoring Unit, Singapore, January 1965-January 1966: complete set of 'Kenjataan 2' in Indonesian’, see FO1110/2356, UKNA. And for the Report on operations by the South East Asia Monitoring Unit, Singapore, January 1965-January 1966: complete set of 'Kenjataan 2' in English, see FO1110/2357, UKNA.