A festival held in honour of the writer in his hometown offered up some surprises

Taufiq Hanafi

I arrived in Blora on the morning of Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s birthday—Pramoedya, or Pram as we know him; a world-class writer, and perhaps one of Indonesia’s greatest sons. I had come deliberately, with high hopes, to take part in the Festival Blora ‘Seabad Pramoedya’ (A Century of Pramoedya), and to witness him there—in spirit—radical and still resisting.

That morning, Blora felt festive, grand, alive. The festival’s opening was held at the Pendopo Kabupaten. There, the air was thick with celebration and official speeches. Two stood out to me. One from the Bupati (regent), another from none other than Fadli Zon, Minister of Culture of the Republic of Indonesia and a major political figure today.

The Bupati, like most regents of this country, gave a predictable speech, filled with platitudes. He said Blora should not celebrate Pram just this once but make it a regular part of the regency’s cultural calendar.

Then came Fadli. But first, it’s important to mention here that Fadli is the nephew of Taufiq Ismail, a literary figure who stood in fierce opposition to Pram. Pram and Taufiq represented the clashing poles of Indonesian cultural politics, LEKRA and MANIKEBU. Not just different camps, but combative, even destructive toward one another. The last time I saw Taufiq was in Leiden, at his poetry book launch. The disdain he held for Pram was still written all over his face. You could tell he had never truly buried the hatchet.

Naturally, I assumed, Fadli, sharing not only blood but ideology with his uncle, would follow suit. That he would dismiss or discredit the festival. But to my surprise, he didn’t. His speech was measured, even reverent. He encouraged the public to read Pram’s works. He even named each one of Pram’s novels and claimed that he had read them all. Frankly, it was not what I had expected from someone who once publicly rejected everything Pram stood for.

My scepticism is rooted in history. In 2009, Fadli edited a book titled Setelah Politik Bukan Panglima Sastra: Polemik Hadiah Magasaysay bagi Pramoedya Ananta Toer (After Politics No Longer the Commander: A Polemic on the Magasaysay Award for Pramoedya). Published by the Institute for Policy Studies, which Fadli himself founded and chaired, the book was a sweeping attack on Pram’s legacy. Triggered by Pram’s 1995 Ramon Magasaysay Award, it painted him as a cultural tyrant during the Sukarno years.

According to the book, Pram led the suppression of creative freedoms. He targeted non-communist writers, playwrights, filmmakers, painters, and musicians, endorsed book bans and burnings in Jakarta and Surabaya, publicly smeared fellow artists, and terrorized dissenters under the LEKRA/PKI banner. Furthermore, the book accused Pram of glorifying censorship, spearheading ideological purges, and stifling independent publishers, some of whom dared to translate works like Dr. Zhivago. The book also claimed the Magasaysay Foundation turned a blind eye to these alleged transgressions. One of the contributors to the book, unsurprisingly, was Taufiq Ismail.

So yes, it was surreal to hear Fadli urging the nation to read Pram and spread his ideals.

After the speeches, the dignitaries departed in ornate horse-drawn carriages. Fadli and the Bupati rode together in one drawn by a white(ish) horse that oddly reminded me of the one ridden by Maurits Mellema, the cruel, feudal character in Bumi Manusia (1980). The resemblance was uncanny. History repeating? Or just my imagination?

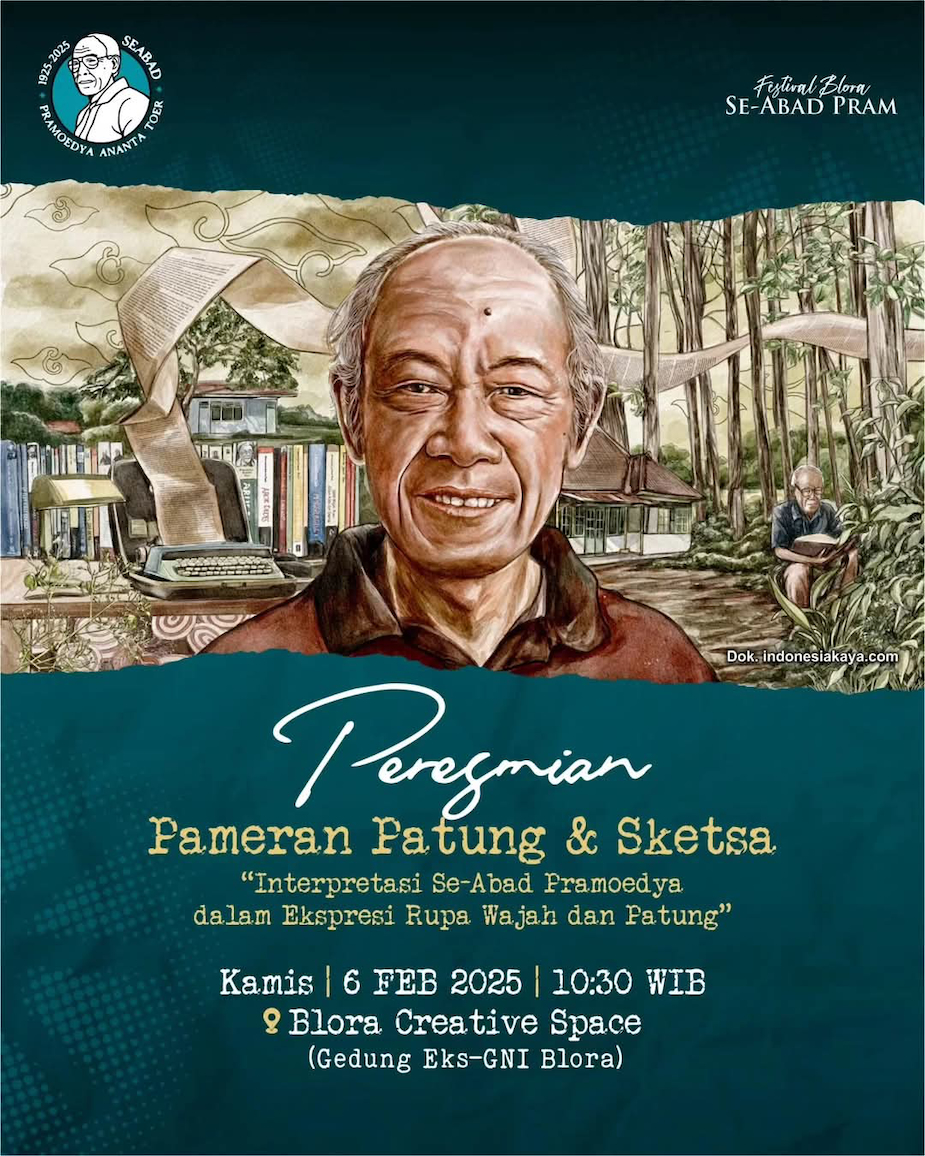

Their destination was Blora Creative Space (BCS) in Kelurahan Mlangsen—a newly painted building that used to be the Gedung Nasional Indonesia. It seems that it had been hastily renovated to host visual art and sculpture exhibitions, supposedly part of the centennial celebration. Everything about it felt rushed. Reluctant, even.

Fadli was there to officially inaugurate the space. I tagged along, briefly.

Inside, I noticed works by Dolorosa Sinaga—still bold, still revolutionary as ever. She was there too, chatting with Fadli. But the room was suffocating, not only in space, but also in mood. People were more interested in shaking hands with officials than engaging with the art. What’s more, sculptures were sloppily displayed. Wooden faces were lined up haphazardly on uneven paving stones outside the building. It felt more like an afterthought than a tribute.

I left early.

Instead, I called a Gojek and made my way to Perpustakaan PATABA, a humble library inside Pram’s childhood home in Jetis, Blora. A large Javanese house with a wide front yard, it is cared for by Pram’s younger brother, Soesilo Toer (or Mbah Soes), and his wife, Budhe Suratiyem. PATABA, short for Pramoedya Ananta Toer Anak Semua Bangsa, was meant to be a space for learning, reflection and dialogue. It’s emblem, a three-legged Cyricllic ‘T’, symbolises the three Toer brothers who founded it.

That afternoon at the Perpustakaan PATABA, there was no crowd, no stage, no fanfare. Just three goats blocking the entrance and their droppings scattered on the terrace. Budhe Suratiyem welcomed me, explaining that the goats were essential. ‘Tanpa kambing itu, bagaimana kami bisa makan?’ (Without them, how would we eat?). Perpustakaan PATABA survives on their backs. And yet, whenever officials come to visit, the local authorities demand that the goats be removed as if their presence was an embarrassment.

Inside Perpustakaan PATABA was falling apart. Despite claims of government support, the front-room walls were cracked. Black mould thrived. Books by and about Pramoedya were decaying, consumed by termites and time. Others had vanished through neglect. Some were stolen. The original copy of Cerita dari Blora was once borrowed by some official from the Kabupaten, and never returned, Budhe Suratiyem told me.

When asked about the grand festival downtown, she gave a faint smile. Turns out Mbah Soes had not been invited. He had gone instead to Tulungagung, over 200 kilometres away, to celebrate his late brother’s centenary with fellow Pram aficionados. Neither he nor Budhe Suratiyem had been informed of the festival’s rundown at the Pendopo Kabupaten. Their absence, one suspects, was deliberate.

That afternoon Perpustakaan PATABA was no monument. It was a ruin. Whatever funding was intended for its upkeep had clearly disappeared. Slipped into hands unknown.

Still, I don’t want to fill this reflection with only bitterness. There were moments of light.

A mural by Pangestumu, a Yogyakarta based street artist, stood out. Pram, smiling wide, cigarette in hand, his chest emblazoned with a red star against a blood-red background. Revolutionary, uncompromising. Fittingly, it was not part of the official program of the festival, nor was it displayed in the BCS.

Another highlight was the memorial lecture by Dhianita Kusuma Pertiwi. A rare breath of clarity. Dhianita spoke of remembering Pram as a way of safeguarding both intellectual and human legacy. She encouraged the younger generation, increasingly distant from his ideas, to read him anew and understand Pram as a foundation for thought, creativity and resistance. Remco Raben’s lecture went deeper into the dialectics of Pram’s work, and Muhidian M. Dahlan’s traced Pram’s political and literary trajectory, his defiance of power, and his continued relevance.

But the Q&A with Remco was scrapped. No space for dialogue. Remco’s session ended without a chance for the audience to respond or challenge. Similarly, Muhidin’s talk was cut short by scheduling delays and the call to Friday prayer. Ironically, these were the sessions that could have kept Pram’s ideas sharp, radical, and infectious. Instead, like Hanung Bramantyo’s 2019 film adaptation of Bumi Manusia, which was also screened as part of the festival, it felt rushed, truncated, and half-hearted.

In the end, Festival Blora ‘Seabad Pramoedya’ felt like pure pomp. Loud in its appearance, hollow in its purpose. Less a tribute than a betrayal. The man who gave voice to the silenced was himself pushed to the margins. His home in ruins. His ideas diluted by those who once opposed them.

Kali Lusi, the river that features prominently in Pram’s work and symbolises his deep connection to Blora’s social realist landscape, played no real role in this festival. Even the long-promised renaming of a street to Jalan Pramoedya Ananta Toer has yet to materialise, blocked by excuses that ranged from public opposition to bureaucratic inconvenience over replacing residents’ ID cards. The street in question, Jalan Sumbawa, was where Pram often walked as a child.

And Fadli? As Minister of Culture, he is now leading a top-down project to rewrite Indonesia’s national history, with full government backing yet heavily criticised by scholars. Amnesty International has called it an act of historical manipulation: cherry picking episodes while obscuring state-sponsored atrocities. Pram, himself a victim of such violence, risks being erased once again. Thus, what Fadli said at the Pendopo Kabupaten that day, his encouragement to re-read Pram, to spread his ideas, was most probably, all mendacities.

But then again, Pramoedya was never meant for that kind of history. He belonged elsewhere. In the margins, in the struggle, in the long arc of resistance. I suspect Pram would have looked at the festival with his usual clarity and called it what it was, a performance. It reminds me of what Pram once wrote in response to Goenawan Mohammad’s sneering criticism back in April 2000. ‘Saya sudah memberikan semuanya kepada Indonesia… Basa-basi tak lagi bisa menghibur saya’ (I have already given everything to Indonesia… Empty formalities can no longer console me). So, maybe, just maybe, it is better that Pram remains where he always stood, not at the centre of official ceremonies but just outside them. Watching, writing, remembering and resisting.

Taufiq Hanafi (hanafi.taufiq@gmail.com) specialises in cultural politics, knowledge production, and state violence. He has a PhD from Leiden University and postdoctoral experience at KITLV and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.