An exhibition at the National Museum shows that marking women’s contribution to the nation remains highly contentious

Vannessa Hearman

Sunting, an exhibition at the National Museum in Jakarta, focuses on women’s contribution to social change in Indonesia, highlighting their leadership and achievements in fields such as education, writing, politics, medicine, the arts and sport. Its title is derived from the hair decoration, the ‘sunting’ and the name of the first newspaper published for women in West Sumatra in 1912, Soenting Melajoe.

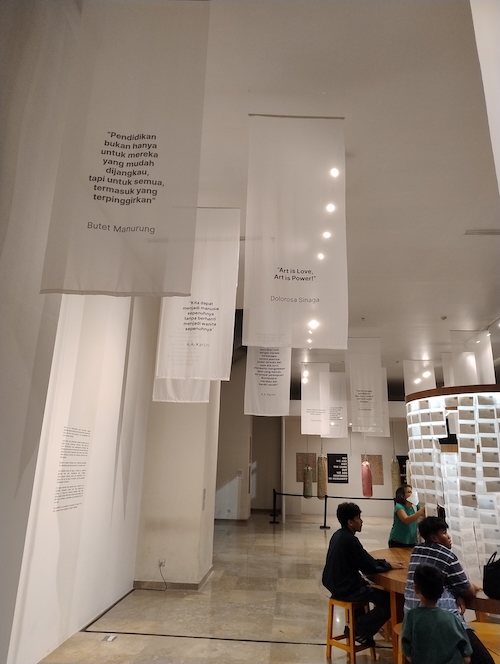

Accidentally seeing this exhibition ‘backwards’ working my way from the curator’s intended end to the start, got me excited. I was hoping this exhibition might be the kind that would challenge accepted gender norms and perceptions about women’s status and place in Indonesia. This ‘end section’ of the exhibition included two artworks. The first was an interactive installation by Ika Vantiani titled Menjadi Dian yang Tak Padam (To Be an Unquenchable Light), consisting of postcards pinned to fabric shaped around a cylindrical tower of light. Museum goers are invited to write their thoughts about the exhibition on a postcard and add it to the installation. Banners containing quotes from prominent women, such as educator Butet Manurung, who works with Indigenous people to promote literacy, hang overhead.

The second artwork, by Bibiana Lee, is titled I (don’t) SEE COLOUR. It consists of punching bags and boxing gloves imprinted with the coloured dots of an Ishihara colour blindness test, and the sign proclaiming, ‘No, we are not the same, but we are brothers in humanity’. The boxing gloves and punching bags refer to the ‘layered violence’ that women suffer – ‘physical, verbal and systemic’. Despite the jarring reference to ‘brothers’ in an exhibition focusing on women, Lee’s work is colourful, provocative and important in aiming to train an intersectional lens on the experiences of women from economically or ethnically marginalised backgrounds.

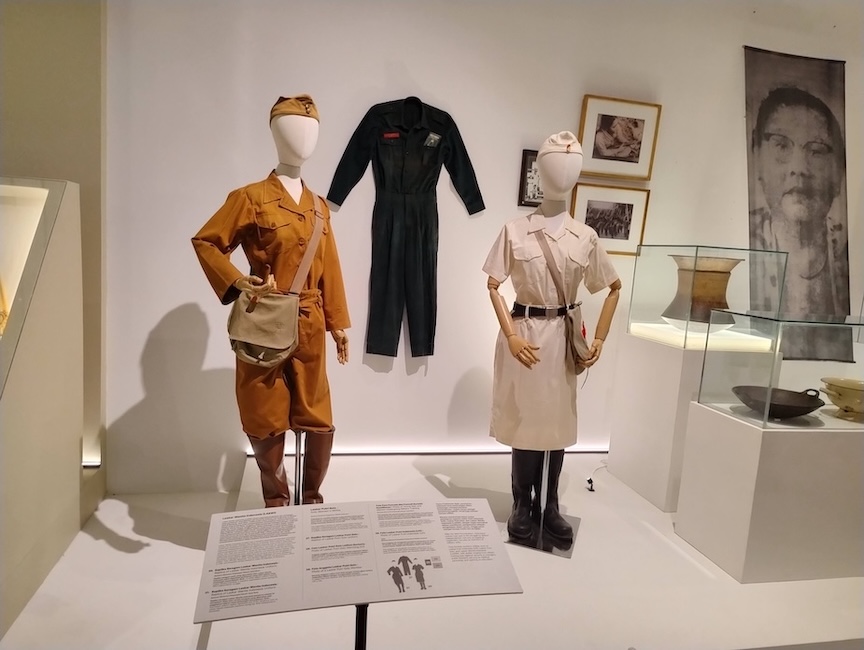

Not unexpectedly, the exhibition heavily emphasises women’s contribution to the Indonesian nationalist movement, including through women’s militias (laskar), organisations and federations such as Perwari (Women’s Association of the Republic of Indonesia), Kowani (Indonesian Women’s Congress), and Aisyiyah, the women’s wing of the modernist Islamic organisation, Muhammadiyah.

The exhibition has assembled a considerable amount of material objects, memorabilia, and ephemera from various sources from all over Indonesia. Considerable space in the exhibition was devoted to clothing and other material objects belonging to the women in focus. Items of clothing displayed in glass cases point to Indonesian women’s diversity, ranging from a bejewelled sequinned kebaya designed by fashion designer Non Kawilarang, to Indonesian writer Ruhanna Kuddus’ batik sarong, scarf and blouse displayed nearby on a mannequin.

The exhibition also examines women’s intellectual and educational work through their writings, focusing on historical figures such as Ruhanna Kudus and Kartini. A wide variety of women’s journals, newsletters, bulletins and newspapers, as well as historic works authored by women, are displayed in a large glass case. As well as Soenting Melajoe (West Sumatra, 1912-21), the display highlights less well-known magazines such as Pahesan, a Dutch language publication for young, educated women, founded by Utari and Utami Ramelan in Solo, published between 1937 and 1941. Utami later became a prominent figure in Afro-Asian solidarity and the Indonesian Peace Council, neither of which is mentioned.

The exhibition also features a selection of books on the history of the women’s movement and organisations in Indonesia, arranged on a round coffee table for visitors to pick up and look at, such as Dewi Anggraeni’s Tragedi Mei 1998 dan Lahirnya Komnas Perempuan. Women’s contribution to the arts is highlighted, for example, through the all-female band Dara Puspita’s LP records and stills from the 1956 film Tiga Dara, directed by Usmar Ismail, as well as a striking sculpture by Dolorosa Sinaga, Solidaritas (2000), referring to the 1998 sexual violence against women, and video work by Arahmaiani, ‘I Don’t Want to Be Part of Your Legend’ (2004).

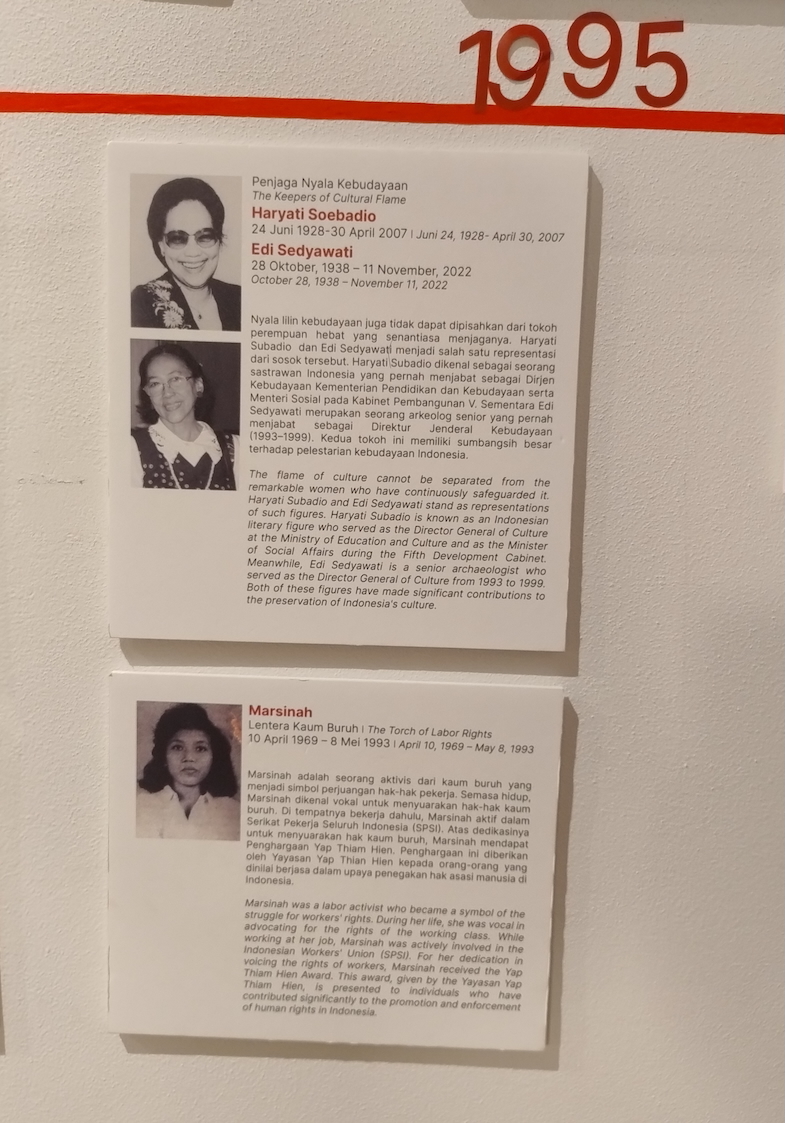

The exhibition stands on more shaky ground when it comes to telling some of the stories entailing human rights abuses that occurred under the New Order. Curiously, the New Order era (1966-98) is referred to as the era of ‘Stability and Development’ rather than by the standard term, the New Order (Orde Baru). The curators’ difficulties are plain to see when we regard the timeline of notable women. Labour activist Marsinah appears on this timeline, but her biographical information is fragmented and is silent about her murder. In 1993, Marsinah, who had been advocating on behalf of her colleagues at her factory, was found murdered. No mention was made of this, nor why she was awarded the Yap Thiam Hien (Human Rights) Award posthumously.

The exhibition also carefully avoids mention of Indonesia’s largest women’s organisation, Gerwani (Indonesian Women’s Movement), nor the persecution of its members, including the use of mass sexual violence against them to destroy the Indonesian Left. S.K. Trimurti, a co-founder of Gerwis (Movement of Politically Conscious Indonesian Women), the organisation that transformed into Gerwani, is referred to as a journalist, and her association with this left-wing organisation is omitted. The destruction of Gerwani marked a conservative reorientation of the Indonesian women’s movement under the New Order regime. The exhibition celebrates former First Lady, Tien Soeharto, wife of authoritarian president Suharto, for her contribution related to Dharma Wanita, an association for women married to male public servants. Scholars argue that Dharma Wanita was symbolic of the New Order’s view of women as being an extension of their menfolk.

The exhibition is careful to include a caveat, stating: ‘The figures featured here represent only a fraction of the countless Indonesian women who have shaped - and continue to shape - our collective progress. Many more names remain absent from history books or grand stages, yet their roles in families, communities, and everyday life are no less vital.’ Gerwani’s omission and the misrepresentations of iconic figures such as Marsinah show the tensions in this exhibition in depicting women’s roles, as on the one hand, these roles have been reconceptualised in democratic Indonesia and, on the other, face attempts to return to New Order era gender perspectives.

One of the smaller objects in a glass case, part of a mix of images and objects only loosely connected, was a little handmade doll. White with tiny black and red stitches, the May 1998 Doll (Boneka Mei 1998) is plain, almost naïve, a quiet reminder of the troubled context of this exhibition. The source of the doll was listed as Komnas Perempuan, the National Commission for the Eradication of Violence against Women. The Commission was formed by President Habibie as a response to the 1998 mass rapes of ethnic Chinese women in Indonesia.

The May 1998 doll is a reminder of the systematic violence against women in the twilight of the New Order regime. The little doll’s quiet presence also seems to pose a question of the extent to which it is possible to rewrite Indonesian history and erase human rights abuses such as the May Rapes. So much of the New Order version of history has already been dismantled, including through government initiatives to establish Komnas Perempuan and to reform the Indonesian education curriculum.

Sunting has attempted to represent a diverse range of women’s experiences in Indonesian public life but has also had to accommodate a range of agendas on how to do so under a new Prabowo government. At the top of the list of pengarah (translated as ‘directors’) of this exhibition is Fadli Zon, Minister of Education and Culture, recently in the news for denying that the 1998 mass rape of ethnic Chinese women despite much evidence to the contrary. While all exhibitions are the products of curation, if the word ‘sunting’ also means to edit, this exhibition has also excised parts of Indonesian women’s history that are uncomfortable or contentious for sections of Indonesian officialdom.

Sunting: Jejak Perempuan Indonesia Penggerak Perubahan (Tracing of Women Who Shaped Indonesia), Museum Nasional, Jakarta, Until 31 July 2025.

Vannessa Hearman (vannessa.hearman@curtin.edu.au) is a historian of modern Indonesia. She is a senior lecturer of History at Curtin University. Vannessa is a member of the board that publishes Inside Indonesia.