Pramoedya depicts the lives of ordinary people during truly extraordinary times

Barbara Hatley

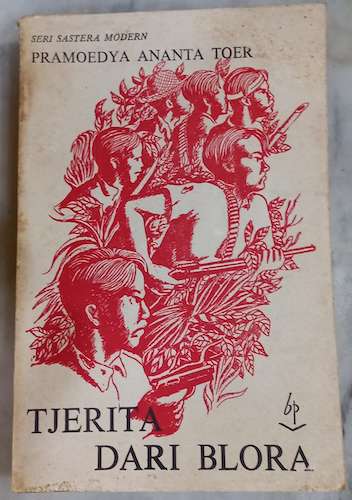

While other contributions to this edition discuss the remarkable achievement of Pramoedya’s novels picturing the creation of the Indonesian nation, my focus is on his Cerita Dari Blora, Stories of Blora, set in the town of Blora in East Java, and relating the experiences of people who have lived there. This choice is motivated by the fact that Pramoedya grew up in Blora, characters in the stories include members of his own family, and that in the late 1970s I had the opportunity to visit the town, where I meet his brother and two of his sisters.

The period when these stories take place, from the late 1930s to the early 1950s, was a time of momentous social and political change, from Dutch colonisation to wartime Japanese Occupation, struggle for control by different political groups, then eventually, Independence. Reading how the lives of ‘ordinary people’ were impacted by these changes is eye-opening and often disturbing.

In the opening story Yang Sudah Hilang (What has Disappeared) the image of the Kali Lusi, the river Lusi, on the banks of which Blora is built, serves as a metaphor for the passing of time, sweeping away the childhood experiences of the narrator leaving only their memory. It might also be seen to provide a framework for the collection as a whole. In the dry season the river water is calm and still, but in the rainy season raging and leaping, tearing away its own banks, like the immense, transformative social and political changes which took place in Blora and Indonesia more generally from the 1930s onwards.

The early stories, set in times of relative calm, depict positive experiences, but also some problematic ones. In Yang Sudah Hilang the child narrator, Aku (I), Pramoedya, describes pleasurable interactions with his mother and the servant who cares for him, also with his father.

On hearing the wind blowing through the bamboo, Aku weeps, afraid the bamboo is crying. His mother however says softly ‘No dear, it’s singing’ then herself sings traditional songs to him, her voice gently soothing his fears.

The maid, Nyi Kin, amuses him by hiding her face behind her selendang (shawl) then pulling the shawl aside and saying ‘Boo!’ And tells him a remarkable story about the bupati (regent) striking the flooded waters of the Kali Lusi with a whip, thus saving the people of Blora from drowning. Aku recalls listening to Nyi Kin telling the story 25 times, always with rapt attention.

Aku also experiences happy interactions with his father. He describes his father returning from the school where he teaches, laughing happily and kissing Aku, who is fed by his mother while father eats dinner. When the father says ‘You’re sleepy’ his mother takes him off to bed, lovingly stroking his thighs as he falls asleep.

But the relationship with his father is sometimes problematic.

When late at night his father has not home returned Aku cries pitifully, ‘Where is father?’ ‘Working.’ Mother replies. But when his father, a teacher, returns at 3am or not until the following day this is clearly not so.

There are problems also in interaction between his father and mother, relating to the father’s absences from home, and the fact that Aku’s mother is strictly religious, frequently praying and chanting Koranic verses, while the father is not.

Yet the story might be seen to end on a positive note, with this advice to Aku from his father ‘You can do what you wish with goods you obtain, also your own body and life, as long as you receive them rightfully.’ His father’s voice, like Aku’s other childhood experiences has been swept away by the passing of time, as the waters of the Kali Lusi in flood tear away its banks. But the memory of his wise words lives on Aku’s mind.

Other stories told by the child narrator depict hardship and suffering.

The family of Kakek Leman in Yang Menyewakan Diri (Workers for Hire) are described as ‘lazy’ by Aku’s parents, and he is warned he’ll be infected with laziness if he visits them. In fact, however they are just very poor, no land to cultivate, no skills, no training, forced to take any job offered. Kakek Leman is even paid by a wealthy man to commit murder. Fortunately, the victim is only badly injured, but Kakek Leman is put in prison. At the end of the story Kakek Leman returns home, but no longer leaves the house, he and his family never interact with the surrounding community.

Poverty is also a factor in the suffering experienced by the title character in the story Inem. Inem is an eight-year-old girl, Aku’s friend, who also cooks for his family, and takes care of the younger children. But when her parents receive a marriage proposal from the son of a wealthy family they accept eagerly. Aku’s mother warns them that Inem is far too young, but the marriage goes ahead. Some days later Aku hears late at night, Inem’s voice crying ‘No! I don’t want to!’ Inem asks Aku’s mother to take her back, but his mother insists she devote herself to caring for her husband. A year later Inem comes again, now divorced, but still Aku’s mother refuses to employ her. For there are several teenage boys, foster children of the family, living in the house, and it would be ‘unseemly’ for a young widow to live there too. So Inem returns home and as a ‘burden on the household’ she can be beaten by anyone - her mother, brother, aunt etc. Aku covers his ears when he hears her crying. But Mother ‘maintains the propriety of her household’.

Inem’s situation involves inequalities of wealth, gender and social class. For Aku’s family are priyayi, a term originally indicating nobility, later expanded to include educated people, with professional positions, such as Aku’s father whereas, Inem’s are wong cilik (little people), commoners.

Then come the stories set in the late 1930s and 1940s, times of dramatic, radical and often catastrophic change.

Chaos and change

There are positive developments at first. Rising nationalism inspired by the swadeshi movement in India, anti-illiteracy courses and publication of material about nationalism, Aku’s father becomes very involved. But he receives warnings from the colonial government about his activities, electricity to his school is cut off and he turns to gambling as a distraction.

Then comes the Japanese Occupation. Blora is invaded, shops are destroyed, the Japanese seize rice harvests for themselves, food is difficult to access. Many people die of malnutrition. Nationalists take control, then ‘Reds’, then the Dutch reoccupy Indonesia. Finally, independence is achieved in 1945.

The story which describes most fully these developments and their impact on the people of Blora is Dia Yang Menyerah (The one who surrenders/ gives in) focusing on Sri, the second oldest sister in a family reminiscent of Aku’s.

When the mother dies at the beginning of the Japanese Occupation, Sri’s two older brothers leave home and go overseas, while her older sister, Is, takes on management of household and caring for the younger children, But Is with her typing skills, obtains a job in a government office. Sri, who is about to graduate from primary school begs Is to wait just the remaining two months of her final school term. But Is refuses, and Sri as the younger sibling must menyerah, give in, leave school to care for the household.

Other ‘surrenders’ follow. The shortage of food during the Japanese Occupation impacts greatly on Sri and her brothers. While their father and Is can use their salaries to eat at food stalls, Sri and her brothers must eat cassava, even the leaves, whatever they can find. Again, Sri gives in, accepts, and this leads to a sense of calmness, as if she’s looking down from a great height. And when Sri and her siblings’ stomachs growl with hunger they simply laugh mockingly, telling them this is tirakat (ascetic fasting) in order to fulfil a wish or reach a goal.

Eventually the Japanese are defeated and a nationalist government established. Is joins the organisation Pesindo (Pemuda Sosialis Indonesia, Indonesian Socialist Youth) and ‘blooms’ as a pemudi revolusioner (revolutionary young woman). Father becomes active again, setting up anti-illiteracy courses. But after the Reds, whom Father regards as ‘rebels’, take control, a group of soldiers come to the house and take father to prison.

Is returns some days later with a group of soldiers; the commander states that Sri and Diah must join them. Is points out that the two girls look after the household; in that case one must join. Diah is willing, but Sri says Diah, who is much cleverer and more useful to the family, should stay with them, she will go. So, ‘For the umpteenth time in her life Sri surrendered to protect the welfare of her family.’

After Sri leaves, Diah and her brothers survive by selling banana leaves from their garden to tempe (soybean cake) sellers. Rather than rice, they eat the roots of cassava plants. ‘Fast stomach, fast!’ they say, following Sri’s example. And when one of them laughs at their suffering all join in. They understand that in surrendering they’re doing nothing wrong, instead ensuring that they will continue to live.

Change comes again. Soldiers from the Siliwangi division of the Indonesian army attack the Reds. And as the Reds retreat, they loot Blora residents’ houses and gardens. They also burn down the prison where father is imprisoned.

Then more change, as the Dutch re-occupy the Blora area. And at last Sri returns – a thin, emaciated figure creeping through clumps of bamboo. She had walked through forests, with only young tree leaves to eat and creek water to drink until at last arriving home.

The story ends with these words from Sri to her siblings and her own heart. ‘Let this all happen. We have to be able to forget about ourselves, regard ourselves as not there. And everything will proceed smoothly.’

And Diah’s reply, ‘Let the scoundrels remain scoundrels, and the good stay good. We five accept things as they are. There is no use rebelling.’

Visting Blora

My own impressions of Blora were formed in 1978, when I was living in Yogyakarta. I had met a student at Gajah Mada University who was from Blora and was about to return there for a few days and suggested I go with him.

A former servant of Pramoedya’s family provided the address of a Pak M, related in some way to Pramoedya. Arriving at the house, through a window I saw a photograph of President Suharto, and wondered if we were in the right place. I was shown through into a back room, its walls adorned with photos of President Sukarno, and to my delight Pramoedya. A woman of about forty-five entered the room. She had a long, lean face and serious expression, unmistakenly similar to that of Pramoedya. It was she, Nyonya M, who was related to Pramoedya – she was his sister, and the tall, thin man who followed her into the room was his brother, Pak W. Pak W revealed that he had recently returned from Buru Island where he too, like Pramoedya, had been imprisoned.

We began talking about Pramoedya’s writings and the pictures of his family and Blora. Nyonya M pointed to a photo of a gentleman with a waxed moustache and hair parted in the middle, her father. The school he founded, which was originally used as a dormitory for teachers, was situated just around the corner from this house. Under suspicion from Dutch authorities because of his nationalist activities, Pramoedya’s father was banned from teaching at the school from the early 1930s onwards and forced to return to a government-controlled school. Depressed and angry, he turned to gambling as a ‘distraction’, to the outrage of his strictly religious wife, as described in the Cerita dari Blora stories. I ask about other characters and incidents from the stories – the servant Nyi Kin, the little girl Inem forced to marry at the age of eight? Yes, all true Nyonya M affirmed.

What of the sufferings of the family during the Japanese Occupation and Revolution described in the story Dia Yang Menyerah – is that an accurate account of what happened? What had become of Sri, the girl left in charge of the family who learnt to cope with adversity by shrinking into herself and letting it roll over her? Nyonya M. smiles - she is the Sri of the story. Many of the events of the story are fictionalised, such as the involvement of her older sister with the Communist forces and the imprisonment of her father. But it was true that after her mother died during the early months of the Japanese Occupation, she had to leave school at the age of ten to look after the family, while her father and older siblings were away or working. Food shortages meant that the family often went for months without rice, eating only cassava. Any leaves or plants would be used for soup or sold; Nyonya M collected and sold banana leaves.

I ask if she recognises her own attitudes in Pramoedya’s description of her ‘surrender’ to hardship and misfortune – did she ever speak in this way to her brother? She says she can’t remember what she might have told Pramoedya. But she does recall a little refrain the children would sing in the evenings - Sole peng, sesok gepeng - ‘Tomorrow they’ll be flat, as flat as deflated tyres’ while patting their empty stomachs, dancing about laughing at their hunger. At the time she never thought of her future - where all this would lead - just of each days’ needs.

I ask about the old family home – is it still standing? Yes. Pak W offers to take me there. The high-ceilinged, sparsely furnished sitting room is presided over by a portrait of Pramoedya’s father. It is the original painting from which Nyonya’s M’s photo was taken. The woman who greets us has the same long, lean face as her sister but is extremely thin. Talking with Nyonya M about her experiences of thirty years ago had felt like revisiting sufferings long since left behind; with her sister I fear we may be discussing something all too painfully present.

She recounts how she left school at 14, got a job as a typist in the subdistrict office, and became involved in politics but only in a minor way. In 1946 she married a soldier in the Republican army and moved with him to postings in Kudus, Rembang and Kediri. When Kediri was taken by the Communists in 1948, she and her husband fled to Blora, walking because there was no transport at that time. Weakened by the physical suffering and fear she became ill with TB. For months she could barely eat and has never been able to regain the weight lost. She had a child, but it was born prematurely and died a few days later. Her husband died in 1953, probably also from TB. She herself spent time in a sanatorium and has recovered from TB but says her ‘soul will never be cured’.

Pak W and I then continued our walk, from the old house to the banks of the Kali Lusi. The river should have been shallow and calm at that time; its dry season condition as described by Pramoedya. Instead, swollen by unseasonable rains, it was in raging, devouring flood. A huge chunk of earth and bamboo ripped away from the opposite bank lay marooned in the middle of the stream, while smaller clumps swept rapidly by. This river could be seen as a powerful symbol of turbulent social and political change as suggested in Pramoedya’s writings. The suffering and misfortunes of Pramoedya himself, his brothers and the sister living on alone in the old house might be seen reflected here too.

By contrast, might Nyonya M's comfortable situation be seen as a form of ‘reward’ for her ability, as described by Pramoedya, to remain detached, inwardly calm, accepting the inevitable? Is this what has enabled her to survive and fulfill the role of a woman of her station, raising and caring for her children, maintaining the family heritage and cultural values?

Does Pramoedya himself acknowledge that acceptance/surrender is often the best/only way to survive in times of devastating conflict and suffering?

Barbara Hatley (barbara.hatley@utas.edu.au) is a former lecturer in Indonesian Studies at Monash University and Professor of Asian Studies at the University of Tasmania with an ongoing interest in Indonesian literature and performance.