The resource frontier is… our own body!

Fathun Karib

‘I’ve never read Marx’s Capital, but I have the marks of Capital all over me’ (Big Bill Haywood, 1869-1928).

‘Capitalism not only has frontiers; it exists only through frontiers, expanding from one place to the next, transforming socioecological relations...’ (Raj Patel and Jason W. Moore).

William D. ‘Big Bill’ Haywood was a mining activist in the United States in the early twentieth century. He understood the realities of capitalism and mining not merely through books but by personal experience. Bill’s experiences as a miner and an activist member of the Industrial Workers of the World left him feeling the wounds and signs of capital in his own body. His story inspired the American historian John F. Kasson, for example in his article ‘Follow the bodies’ (2007). Kasson believed that one can grasp the working of capital on human experience by observing and ‘following’ the body. This could be a research strategy that is broadly applicable for understanding capitalism and socio-ecological transformation. It could complement and enrich strategies based on observing commodities, and observing personal biographies. I have explored these earlier in Inside Indonesia’s Bacaan Bumi series (in bahasa – here, and here). Mining commodities can only be produced and circulate by means of the body. Such bodily experiences in turn attach themselves to a person’s identity and shape their biography.

The body as frontier

Capitalism and Empire work and can only exist at the frontier. Mining binds one to the other. There is no empire without the frontier, and no capitalism without mining. Historically, this empire-frontier-mining relationship has existed in the global capitalist system since the sixteenth century. It started with the brutal gold and silver mines in the Americas. Their histories, though – histories of capitalism, empire, and mining – often leave us to imagine them happening ‘out there,’ as forces affecting our lives from the outside. We might read about the arrival of a foreign company backed by its government to operate a mine to extract mineral resources, and we think: ‘Interesting, but it doesn’t directly concern me.’ In fact, empire and mining are entrenched in ourselves and our bodies, in ways we overlook at our peril.

Critical thinkers have identified the human body as a site of accumulation. In the context of capital expansion, such as mining, socio-ecological changes do not occur solely in nature or the environment outside the human body. Extracting gold, nickel, coal, and other earth materials not only transforms the geography and geology of those areas. It creates what can be referred to as a ‘commodity frontier.’ This is the boundary between areas impacted by production and those that remain untouched and natural. As the frontier is established, local people living there experience socio-ecological change. The geographer David Harvey writes about ‘the body as an accumulation strategy,’ and Silvia Federici on ‘women, the body and primitive accumulation.’ Other feminists like Gloria Anzaldúa and Ann Stoler also view the body as an (‘interior’) frontier. Reading their work will expand our understanding that our bodies themselves represent frontiers that undergo socio-ecological changes, alongside the environments surrounding mining sites. In this sense, the mining frontier extends beyond just the natural landscape. It encompasses the human body as well.

This article imagines mining in extractive regions not only as a part of global capitalism but also as attached to, and penetrating, our own bodies, our selves! The experiences of Big Bill in the United States early in the 20th century, and of various people in Indonesia, allow us to trace how empire and mining are imprinted on our bodies in the 21st century. This edition of Inside Indonesia describes bodily experiences in frontier mining areas such as Banyuwangi, Trenggalek, Morowali, and Kolaka. But our study could just as easily be extended to those who live in cities such as Jakarta, Semarang, or Surabaya.

Machine

Extraction is the act of taking something, particularly through effort or force. Mining is a specific type of extraction that involves obtaining earth materials such as gold, silver, copper, tin, and nickel. It is essential to recognise that both general extraction work and mining require the involvement of two bodies: humans and the earth.

The potential for labour resides in the human body. It is realised in the labour process, where people extract resources from the earth. In the mining process, not only is the earth subjected to extraction as minerals are transformed into raw materials, but so is human labour. Companies utilise workers' bodies, which, in turn, extract materials from the earth's body. Realising this helps us understand that mining impacts nature, the surrounding environment, and the human body. It produces ‘socio-ecological change.’

Karl Marx and Silvia Federici remind us that the most sophisticated machine developed by capitalism is not the steam engine or other technologies. It is rather the transformation of the human body into a machine. This mechanisation of the body is rooted in Cartesian philosophy, which separates reason from the physical body, reducing the latter to a mere mechanical entity. Marx and Federici argue that this mechanical view of the body is akin to seeing it as a machine – that is, specifically the body of members of the working class. Intellectuals today discuss machines and AI. In fact the first form of artificial intelligence created by capitalism was labour performed by the human body. Labour served as the initial machine, the initial AI, developed by early capitalism.

Toxic bodies

But there’s more to extraction than producing raw materials to feed into the factories. The body in the mine is exposed to toxic materials. Mining not only produces commodities but also generates waste. This is defined as any substance or byproduct that is discarded when it is no longer useful after a production process is completed. While waste can sometimes be repurposed into materials for the production of different commodities, it can also pose significant risks due to the harmful elements it contains. These toxics can adversely affect both the human body and the environment. In mining areas they include geological waste, carbon emissions from hydrocarbon energy, and various forms of garbage. These can contaminate water, air, and soil. The miners who live in these regions are often the first to experience the negative effects of their toxicity. Surrounding communities also suffer, particularly those whose land was previously seized for mining activities but who continue to reside nearby.

The articles in this edition of Inside Indonesia provide many examples of materials that become toxic in frontier mining areas. In Kolaka, Southeast Sulawesi, the production of nickel has led to red mud floods because trees have been destroyed. In the ‘Sacrifice Zone,’ Mahesti and Gerry illustrate how the production process generates waste from refining in the smelter, which is then either stored behind a temporary dam or simply dumped into the sea. The ocean itself becomes a sacrifice zone, polluting the waters near every coastal lateritic mine. This in turn affects coastal communities even some distance from the mine. The concept of the sacrifice zone can apply not only to the sea and the mine’s immediate environment but also to the living body, where dangerous wastes can accumulate. Fish, shrimp, and other food sources have also become contaminated, and can affect the bodies of those who consume them.

In Central Sulawesi, people are metaphorically turned into dirt through their bodies. Limestone frontiers have been created to support President Jokowi's ambitious new capital city of IKN. Here, as Jiahui describes it, humans are ‘producing dirt, consuming dirt, and ultimately becoming dirt.’ Toxic dust pollution in the Palu-Donggala area affects both the local population and the earth. Local people encapsulate this dual effect in the slogan they paint on their protest sign: ‘IKN Damages the Lungs of the World and the Palu-Donggala Community.’

In Trenggalek, the fear that ‘heaven’ might burn made villagers and activists react against a gold mine opening in their area. People there consider the karst landscape, forests, and freshwater sources elements of heaven. Resisting gold mining means resisting a future in which heaven is lost and the environment is toxic. In a place like Sumberbening, the villagers work to sustain heaven. One successful approach has been participation in the government's Climate Village Program. In 2022 the village received an award for their efforts to preserve the forest, maintain springs, and manage waste. They believe that heaven doesn’t just fall from the sky; it is actualised through the conservation of nature and the struggle against harmful gold mining activities.

Industrial mutants

The issues of waste, toxicity, and the human body emerge from all the cases in this edition. However, one critical aspect is still missing: a discussion of how mining affects the bodies of the mine workers themselves. Connecting the impacts faced by mine workers with those experienced by farmers, fishers, and indigenous peoples—whose bodies are also contaminated by toxic waste—will unite us all. We can reach a collective understanding of this bodily crisis. Our own bodies become sacrifice zones because of the accumulation process that I express in the songs below. I wrote them for my band ‘Cryptical Death’ (with thanks to Walker DePuy for the translations).

The second song refers to bodies contaminated by hazardous waste in various frontiers as industrial mutants. ‘PLTU’ - Pembangkit Listrik Tenaga Uap – is the steam-powered generator that produces most of the country’s electricity. It is fired by fossil fuel: coal, diesel or gas. In our song, we twisted the acronym PLTU so it became ‘Polusi Laut, Tanah Udara’ (Sea, Land and Air Pollution).

|

Perampasan tanah air udara - porak poranda sumber hidup petani, nelayan - buruh merana Negara agraria hilang sawah dan padi Maritim Nusantara - tinggal cerita Pulau Banda, Sangihe sampai Papua Rata oleh serakah - nafsu manusia Cangkul, cangkul, cangkul yang dalam Keruk, keruk, keruk yang dalam Akumulasi...akumulasi...akumulasi… Akumulasi...akumulasi...akumulasi… |

Accumulation The plundering of land, air, and water – devastated An agrarian nation without fields and rice From Banda Island and Sangihe to Papua Dig, dig, dig deep Accumulation... accumulation... accumulation |

|

PLTU, PLTU, PLTU PLTU, PLTU, PLTU Elektrifikasi Fosil energi Limbah polusi Polusi...Laut...Tanah...Udara Tubuh tercemari Rasuk hati Terbakar diri Kami Mutan Industri... Kami Mutan Industri... Kami Mutan Industri... Kami Mutan Industri... Polusi...Laut...Tanah...Udara |

PLTU Electrification Pollution... Sea... Soil... Sky Our bodies—contaminated We are Industrial Mutants... Pollution... Sea... Soil... Sky |

The environmental NGO Walhi researched the impacts generated by three of the largest PLTUs in Java. They observed a slow but steady degradation of ecosystems in their vicinity, deteriorating economic conditions, as well as negative health impacts on people. In frontier coal-mining areas, the industrial mutants are miners and residents living near production sites. But when the coal is burned in the PLTU and converted into electricity for all Indonesian citizens, we are also creating a new category of industrial mutants around the power plants. Toxic-bodied industrial mutants are therefore not limited to rural or indigenous areas but are present also in urban environments.

Urban toxic

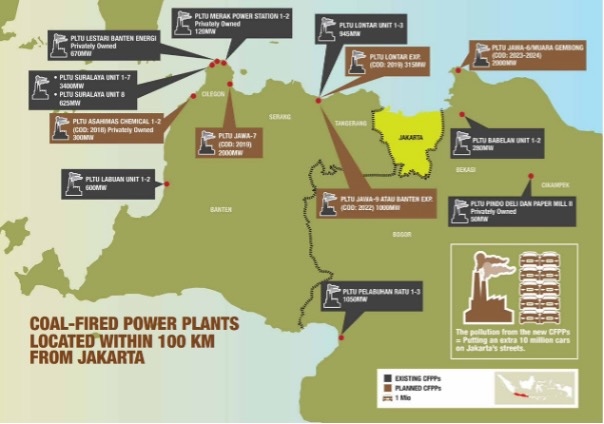

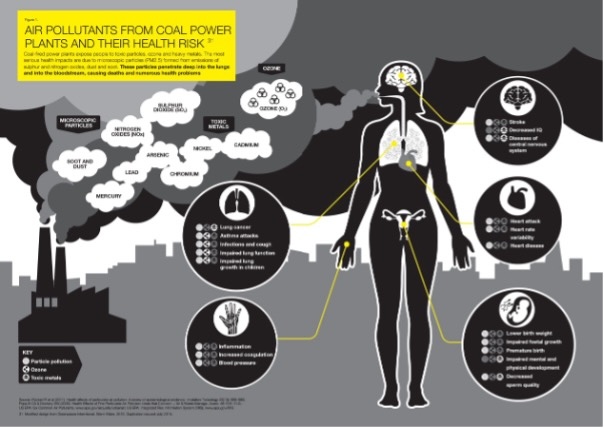

Electricity production from the many coal-fired power plants in Java generate carbon dioxide air pollution, as well as nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide, and fine dust containing heavy metals such mercury, lead, arsenic, and cadmium that go deep into people’s lungs. According to a Greenpeace report, Jakarta is surrounded by ‘silent killers‘ that help produce some of the worst air pollution in the world (Figure 1). Another Greenpeace report highlights the long-term health impact of disease and organ damage caused by coal pollution (Figure 2). Much of this coal comes from mines in Kalimantan. Transporting it in barges also pollutes the ocean and the coral reefs of beautiful places like Karimun Islands.

Industrial mutants also arise from the consumption process. An example is the use of nickel from Sulawesi or North Maluku to make batteries for electric vehicles and mobile phones bought by city dwellers. Many consumers think ‘clean energy’ is good for the environment because EV’s use no hydrocarbon fuel. They forget the environmental damage caused by digging up the nickel. (And they forget that the electricity their EV runs on is probably produced in a coal-fired power plant (Figure 3). Meanwhile, people continue to use plastic as if there is no tomorrow. This is simply a different form of fossil fuel, with all its associated damage.

There are three reasons why people deny the negative impact of mining. The ‘immediacy factor’ means we often do not perceive air pollution and environmental damage as threats that affect our immediate future. The second factor is ‘proximity’ – many city residents live too far away from the ruined landscapes around the mine-sites to recognise the impacts. The third factor is ‘naturalisation’ - we assume the environmental changes associated with mining are simply part of nature. These factors complicate environmental politics and hinder the formation of citizen awareness about the implications of mining.

Cycles

Our times are marked by the intertwining of an environmental crisis and intense competition between rivals the United States and China. The trade war championed by Donald Trump, and the fact that Elon Musk has tied his agenda to Trump, highlights a significant crisis in the historical tendency of capital accumulation. But there are precedents. The early 20th century also saw a struggle over energy sources - the transition from coal to oil, perhaps not unlike our own transition to renewables. Also, the 20th century saw competition between American and German car manufacturers, while in the 21st century Americans are competing with the Chinese over electric vehicles. The cycle of capital and imperial conflict between old and new hegemons from 1925 to 1945 culminated in war.

Will this cycle repeat now itself? This question underscores the importance of understanding how the interests of empires and capital shape our existence, turning us into what can be described as industrial mutants. The various industries that rely on mined materials impact our bodies and are deeply rooted in the interests of these empires and capital. By building awareness of the connection between the various industrial mutants — mine workers, those living near mines, and city dwellers who suffer from mining pollution and consume related products — we can create an alternative politics from the ground up, a politics from below. We must start by recognising that our bodies are affected by toxins; that we are all industrial mutants, and victims of the ideals propagated by the mining interests of Empire and Capital.

|

Penambang cinta I. Semoga aku bukan penambang cinta. Datang mengetuk, lalu melobangi hati. Berapa banyak orang tersakiti, Karena dibolongi tambang lalu ditinggal pergi. II. Isi bumi dan isi hati digali Lobang menganga, orang tercebur tanpa bisa kembali. Betapa banyak penambang cinta datang dan pergi. Mengucap janji bahagia tapi hilang tak terganti. III. Ibu bumi adalah cinta pertama Kenapa kau rusak dan buat merana Berapa banyak yang telah dan akan menderita Lubang tambang, nestapa anak semua bangsa Karena tambangmu, imperium berjaya! |

The love miner I. II. III. |

Fathun Karib is a postdoctoral fellow fellow under the ARI-DIJ Research Partnership on Asian Infrastructure at the Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, and a lecturer in sociology at UIN Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University, Jakarta. He is also vocalist in the grind punk band Cryptical Death.