Photo-essay: Dissent and struggle are persistent themes of images adorning walls across East Timor

Chris Parkinson

The post-independence period has seen East Timor oscillate between stability and conflict. Graffiti, an uncensored medium accessible to all, reflects this instability. Throughout the country, graffiti images draw upon themes of resistance and struggle that emerged during the Indonesian occupation. Today these images reflect the contemporary struggles facing the people of independent East Timor.

The following photos were taken between 2004 and 2008. They are a small representation of graffiti that can be found across the thirteen districts of East Timor. The supporting text is based on what I have been told about the images by various people. It is important to remember that every viewer of graffiti bring his or her own experiences and values to interpreting the images. This means that there could be diverse and alternative explanations for these images.

Blok I |

The Indonesian system of ‘blocking’, where neighbourhoods are named and zoned using an alphabetical lettering system, is still used in East Timor. This burnt and destroyed building on the busy Audian road has a ghostly feel to it. The continuing use of the terminology of blocking is a reminder of how local people still use a foreign and borrowed system to articulate ownership of area.

|

Lingkaran Setan |

This piece used to be on a corner block in Audian, a suburb of Dili. It was, however, recently removed to make way for a new housing development. The text, in Indonesian, means ‘Vicious Circle,’ and reflects how some East Timorese see themselves trapped by the cyclical nature of violence.

|

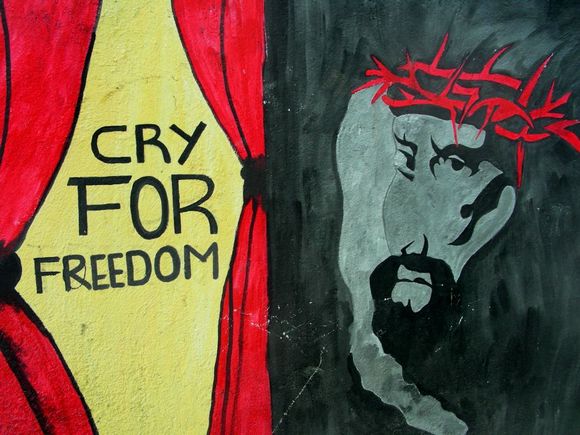

Cry for Freedom |

This image was painted by El Diablo (The Devil), a small group of approximately 20 men in the suburb Bairo Pite in Dili. The image illustrates how notions of freedom for many East Timorese were, and continue to be, closely connected to the church. This image is part of a montage of pictures on a wall that adjoins the clubhouse of the group. Despite their name, El Diablo’s activities and artwork are faithful to notions of education and use positive religious iconography.

|

Man in bottom |

This image is found in the Dili suburb of Vila Verde. It dates back to early 2000. More humorous than other images produced at that time, this picture serves as a metaphorical description of Indonesia’s occupation, with East Timor assuming the role of the squashed figure inside the bottom of the hulking yellow individual who could possibly be the Javanese wayang character Semar.

|

Lose one, get two |

The building on which this image is painted used to be a community health meeting room in the district of Liquica. The phrase ‘Esa hilang dua terbilang’ (for every one lost, two more will take their place) is the motto of Kodam Siliwangi, a division of the Indonesian army that was formed in West Java during the fight for Indonesian independence. The slogan originally has positive connotations. However, in the context of East Timor it is associated with fear. This graffiti was written by troops from the Indonesian Brimob (Brigade Mobil, or Mobile Brigade), and served as an unfriendly reminder of the violence of the Indonesian occupation. According to a group of young people and a community health practitioner who had worked in the building, the text refers to what the Indonesian soldiers would do if an East Timorese citizen escaped their capture: if one individual escaped, two would be captured, tortured or murdered to compensate for the loss.

|

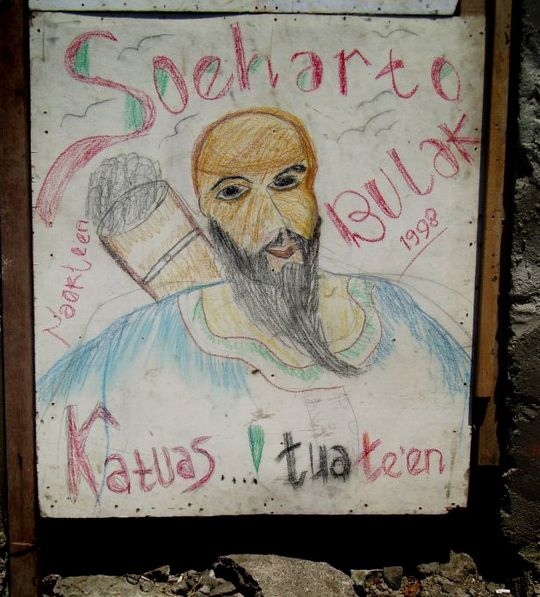

Soeharto (Suharto is crazy! Old man! Alcoholic. Thief) |

This image was drawn by children who played in an abandoned building close to an unused doorway down a side street in Kaikoli, a suburb of Dili. The drawing was made in 2004 but was removed a year later. The inclusion of the year 1998, as opposed to the year the drawing was made, refers to the year Suharto relinquished power.

|

Rekonsiliasi |

Different parties claim ownership of this piece which is at the back of the old community centre and basketball court in Los Palos, a town in the east of the country. A small gang of children argue they made it, as do the so-called ‘Galaxy Boys,’ a group of established artists and musicians originating from Los Palos. The image captures the multiplicity of sentiments about reconciliation. For some, dancing with the devil is a necessary part of moving their lives forward after independence. ii

Chris Parkinson (chrs.prknsn@gmail.com) is a photographer and communications consultant who lived and worked in East Timor for four years. He currently lives in Melbourne and is working on a book on the graffiti of East Timor.

All photos in this essay are by Chris Parkinson