Documentary film and social media bring the fires closer to home

Edwin Jurriëns, Aryo Danusiri and Rugun Sirait

The fires in Central Kalimantan are real. In 2023, the fire engulfed around 1 million hectares. Since the late 1990s, the magnitude of forest fires and haze disasters have increased. The 2015 crisis, with 2.6 million hectares burned, was a significant event that urged the government to acknowledge and respond to these disasters. The fires destroy flora and fauna and impact people’s health, everyday life, and sense of self and community. Beyond those who are directly affected by the disaster, wider community engagement with these problems is limited. This is due not only to lack of media attention, but also to the nature of conventional news reporting in the ‘(c)old’ print and broadcast media, which tend to situate the fires in geographically and emotionally faraway places.

This article focuses on efforts by local young media producers to metaphorically ‘burn’ the physical and virtual distance between those who live in the midst of the fires, and those who live far away, to give urban Indonesians and media consumers outside the country an intimate, sensory experience of the fires. They use what are referred to as ‘hot’ personalised audio-visual strategies in documentary and social media, to go beyond the limitations of the cold media to build awareness and empathy. We will focus on two case studies in the context of the 2024 fires in Central Kalimantan. The first is the use of documentary by the Palangka Raya-based Ranu Welum youth and media foundation, and the second examines the use of sound by the creators of TikTok videos about the fires.

The Ranu Welum Youth and Media Foundation

The Ranu Welum foundation is an activist response to the destruction of forests, water and air pollution, and confiscation of lands by logging, coal and gold mining, and palm oil companies in Central Kalimantan. One of the taglines underlining its activism is: ‘The world will not be destroyed by those who do evil, but by those who watch them without doing anything’. The foundation carries out research and undertakes practical action against the negative impact of environmental destruction on people’s health, economic conditions, social structures, cultural identities, freedoms and rights. This approach is reflected in its name ranu welum, which means ‘the water of life’ in the language of Dayak Maanyan, a predominantly Christian ethnic group from the provinces of Central and South Kalimantan. The foundation’s name underlines its approach which does not see environmental conservation in isolation, but intersects with the preservation of culture and the struggle for indigenous rights.

Ranu Welum utilises textual and visual discourses, action programs and networking to sustain its struggle and make the Dayak plight known to the world. It uses digital film, video, and social media as tools of information and communication, storytelling, intergenerational knowledge exchange, and activism. Its media productions highlight female agency and communal values in tackling environmental, social, and/or personal issues. They give a voice to minorities that are underrepresented in the Indonesian mainstream media and broader socio-political realm, in which majority perspectives – adult, male, Javanese, and/or Islamic – prevail. Since 2018, the foundation has also organised an annual International Indigenous Film Festival (IIFF) in four different locations, Palangka Raya (Central Kalimantan), Ubud (Bali, in collaboration with New Zealand photographer David Metcalf), Kuching (Malaysia) and Bhubaneswar (India).

Many of Ranu Welum’s films are written, directed, or produced by its founder, Emmanuel Shinta, who is a Dayak Maanyan filmmaker, author, and environmental activist. With her creative and communication talents, she has been instrumental in translating between local and foreign languages and concepts; mediating between national and international stakeholders; and giving publicity to the foundation’s social and environmental causes. Her success in communicating the Dayak cause on a global level is demonstrated by her invited talks at numerous international forums, including the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival (2016, 2018), the Global Landscapes Forum (2019, 2023), TEDx (9 December 2020), and the Earthna summit (2023). She was appointed member of the environmental meeting of the Advisory Board of the United Nations, Stockholm 50+, which was held in Stockholm, 2-3 June 2022.

Gendered documentary

Shinta’s two-film documentary series When Women Fight (Part 1 and Part 2) covers the start of Ranu Welum’s activism by focusing on the actions and perspectives of the female leaders of the foundation’s environmental and health campaigns, which includes the filmmaker herself, Roro Ardya Garini and Lina Karolin. Their presence, activities and statements in the films make the complex issues relatable to young and international audiences by intersecting the personal and the political, the private and the public, the individual and the communal, the online and the offline.

Part 1 (2016) of the documentary, published on YouTube on 2 May 2016, opens with footage of Shinta leading a street demonstration in front of the office of the Governor of Central Kalimantan in Palangka Raya during the 2015 haze.

Speaking into a megaphone she expresses people’s fear and frustration and calls for politicians to take responsibility and act. In different sections of the documentary, Shinta has a strong bodily presence and appears wearing headphones and speaking directly to the camera against a background of rice fields, as if intersecting the online and offline worlds. She contextualises and politicises the haze with personal experiences and broader social and historical background.

Like the other female protagonists in the documentary, Shinta conveys information with a voice and facial expression that combine a spirit of activism with feelings of anger, sadness and exhaustion. Her words and appearance show that her political activism is rooted in lived experiences and is both individual and communal in nature. This is also reflected in Lina Karolin’s emotional account of her personal experiences as a volunteer. These experiences range from receiving the gratitude of parents for the donation of masks, to the challenges of reaching remote locations, supporting ill children, and fighting physical and mental fatigue.

When Women Fight, Part 2 (2018), published on YouTube on 17 August 2019, also genders and politicises the struggles for environmental and social justice by presenting women’s bodies and experiences. Some of the most impressive images in the documentary show Shinta in the thick of things, at the border between the Taruna and Tumbang Nusa villages in the Pulang Pisau regency in Central Kalimantan. She is seen sweating and having difficulty breathing from under an oxygen mask. In the background, the yellow and red flames of wild peatland fires contrast with the pitch-black night. Shinta explains the fires are deep and spreading fast, while she and her fellow volunteer firefighters have only limited access to the lands and are forced to continue working through the night.

Shinta and her fellow female activists have a strong visual presence and personal storytelling style in Ranu Welum’s documentaries. They connect the lived experiences of individuals that young audiences can relate to, with the broader historical and political contexts of the social and environmental issues. Through real-life or virtual meetings with other prominent female and male activists, they also interlink the Dayak activism with the struggle for indigenous rights and social and environmental justice worldwide. Despite enduring a heavy physical and mental toll, these Dayak activists are committed to learning from and with others and continuing their fight.

The burning sounds of TikTok memes

In addition to documentary, another medium for Ranu Welum and other activists and ordinary citizens to express their concerns about the fires is social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok in particular. On TikTok, a For You Page (FYP) provides algorithm-based content that is tailored to the interests of its users. This means users with urban lifestyles and media consumption practices in places like Jakarta may never be fed information about the fires in Kalimantan, which, in this trending digital environment, are kept in the distance. While confronted in their daily lives with high temperatures and drought during a prolonged El Niño season in 2023, city dwellers may be able to relate to the heat elsewhere in Indonesia. For Indonesians who have never or rarely seen a forest in their lives, how can TikTok work as a tool to trigger empathy for their fellow citizens facing fires, especially in Kalimantan?

TikTok memes consist not only of visuals but also sounds. In fact, following these sounds rather than FYP recommendations brings up many viral trends related to the fires in Kalimantan. Sound also has an intimate quality, which, in combination with still or moving images, can bridge the distance between the fires and the media consumers. Moreover, user-friendly TikTok and mobile phone camera applications enable the fast and easy re-editing, re-mixing and re-distribution of audio and visuals. TikTok users can respond to a meme with resonating sounds, images, and videos. The use of jargon, jokes, and music, with the right formula, can produce a ‘hot’ sound trend that will go viral long before being extinguished.

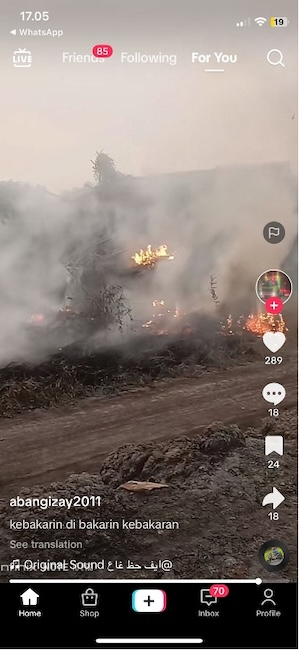

For instance, a video posted on 2 October 2023 by a Tiktok user from South Kalimantan combined images of fire seemingly raging in his backyard, with humorous spoken variations on the word kebakarin (‘to be burnt’) and the sounds of burning leaves and gusts of wind. For over a month, other TikTok users posted a total of 1342 videos responding to the fire theme and sound of the kebakarin meme, with content ranging from mattresses accidentally burnt by the clumsy use of mosquito coils to forest fires in various parts of Indonesia.

In another case, a total of 944 videos responded to the melodious voice of Alint, an MC and singer from Banjarmasin. From the top of her motorbike, she recorded a video of the streets becoming increasingly covered in haze, while cynically narrating, ‘Welcome to South Kalimantan, where haze is one of the annual events that we always celebrate. We celebrate with great joy, by going to the doctor with complaints of respiratory infections, sore throats, coughing, sneezing, shortness of breath, and other respiratory problems …’

Other TikTok users remixed Alint’s voice with still and moving images of people passing through haze-filled streets. Some of them referred to the streets as leading to Saranjana, a mystical city that exists in a myth originating from the people of Pulau Laut in South Kalimantan. In the same way users engaged with the kebakarin sound, repurposing Alint’s voice in their posts, brings the fires to within their virtual vicinity, as well as their real lifeworld. Some fire departments in Central Kalimantan and other areas affected by fires now use the popular sound segments in their public announcements.

We argue that urban social media users who engage with sound trends and listening methods, similar to Ranu Welum’s use of experiential documentary, can make otherwise distant and unimaginable phenomena close and intimate for themselves and the world. Through ‘burning’ barriers and distances of geography, knowledge and empathy, the everyday experiences of (fellow) Indonesians in faraway places become real. This has the potential of bringing people together in ways that go beyond the rather abstract notion of Indonesia as an ‘imagined’ community. Through mobile phones which are equipped with cameras and easy-to-use applications or other technological gadgets, the people who are directly affected by the fires are able to document and share their burnt surroundings with others. Moreover, with the same gadgets and tactical use of TikTok, YouTube, and other algorithm-based platforms, they can further disseminate the social, cultural and health impact of the fires on themselves and their communities in highly personalised ways.

Edwin Jurriens (edwin.jurriens@unimelb.edu.au) is an associate professor in Indonesian Studies and Deputy Associate Dean International-Indonesia at the Asia Institute, the Faculty of Arts, The University of Melbourne. Aryo Danusiri (aryo.danusiri@ui.ac.id) is an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Indonesia, focusing on politics, technology, and care. Rugun Sirait (rugun.sirait@gmail.com) is a freelance researcher, who recently finished a Digital Anthropology master’s program at University College London (UCL). She works in the fields of digital ethnography and film programming. We acknowledge the support of Sarasi Sylvester Sinurat, Head of Youth and Community Department at Ranu Welum.