Jakarta’s urban poor see Habib Rizieq Shihab as a homegrown symbol of resistance and rebelliousness in the midst of their own marginisation

Zaki Arrobi

Habib Rizieq Shihab has often been described as a radical Islamist preacher whose messages are rife with divisive narratives, such as a call for the enactment of Sharia law and inciting hatred and violence against those considered 'deviant' and 'immoral.' Others consider Rizieq and his FPI (Front Pembela Islam/Islamic Defenders Front) as an emerging broker entangled in the game of political elites who attempt to mobilise conservative Islamic constituencies in the context of Indonesia's contentious electoral battles.

But what does a figure like Habib Rizieq Shihab mean for the urban poor residents of the district of Tanah Abang where he lives, especially the Betawi residents? How do they perceive this controversial figure, particularly after the government disbanded the organisation on 30 December 2020 and persecuted its leaders?

Tanah Abang

Over the last couple of years, I have conducted ethnographic fieldwork in Tanah Abang in central Jakarta to understand how different religious actors, discourses, rituals, and materialities play roles in the production of order and (in)security in urban Jakarta.

Situated at the heart of Jakarta’s central area, the district is perceived both as an economic centre and a space of insecurity and disorder. Part of the reason for such a reputation could be attributed to the fact that FPI had its headquarters in the district, just next to Habib Rizieq’s house in Petamburan. Not many know, however, that the FPI was only one among many social organisations that have proliferated in the area. A multitude of ormas (organisasi masyarakat, societal organisation) that mobilise different kinds of belonging —religion, ethnicity, or territoriality— have competed and collaborated to attract the residents and capture a lucrative informal economy in the area. The district has also been known as a ‘melting pot’ where different ethnic communities live together with a considerable number of Betawi people.

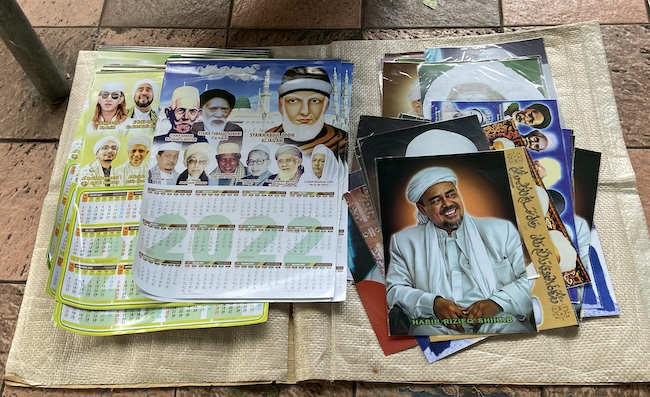

When I started my fieldwork at the end of 2022, the FPI had already been banned and Rizieq, along with other top-rank FPI leaders, were still imprisoned for violating the COVID-related health protocols during the mawlid celebration in Petamburan. Nevertheless, Rizieq’s imagery was very much visible throughout the district. Even though he was still in prison, he still could easily be 'found' in the area. Rizieq’s picture could be seen on stickers stuck to the wall of some mosques and residents’ houses, on posters sold by hawkers after the Friday prayer, or on the local youth and street vendors who wear t-shirts sporting the slogans of the revolusi akhlak (moral revolution).

When I strolled through one of the neighborhood’s labyrinthian alleys, I saw stickers featuring Habib Rizieq pasted on the doors of residents’ houses. These stickers had been partially torn off, presumably to avoid the government's scrutiny after the disbandment and persecution of the FPI, but the words could still be clearly read. They contained a long prayer in Indonesian that asked Allah to bring happiness, health, wealth and to avoid disaster and affliction to the owners of the houses and conclude with the call to print and distribute them to every Muslim resident’s house. The sticker reminded me of a common practice of some Muslims who put stickers of certain Qur'anic verses in their houses, most notably ayat kursi (surah al Baqarah verse 255), to seek protection, prevent calamity and deter theft or burglary at home. This should be situated in the feelings of insecurity that many urban poor residents encounter in everyday life, especially fear of being the victim of theft and petty crime.

I often also found the stickers and posters of Habib Rizieq put together with other Islamic figures like Habib Umar, Habib Syech, the late Habib Munzir, or also Islamic saints (wali) such as Abdul Qadir Jailani or the Wali Songo (the nine revered Islamic saints). Although these habaib and Islamic saints might have very different approaches and messages in spreading the teaching of Islam to Muslim communities, they are all regarded as respected Islamic saints who could bring some sort of 'spiritual protection' to their followers through their 'presence'. Indeed, in many pious Betawi communities, habib, who are believed to be the descendants of the Prophet, are not only held in high social and cultural esteem, but it is believed they can perform miracles. In July 2020, viral footage of 'the invulnerability' of Rizieq's banner when burned by some anti-FPI protesters in front of parliamentary building, is presented by his followers as evidence that he is an Islamic saint who can perform miracles.

A revolutionary saint?

While it is true that the importance of Habib Rizieq should be located in the broader phenomenon of the growing influence of religious figures from the Sayyid community in the urban religious landscape of Jakarta, his popularity seems to move beyond religious persona.

On a typical humid night in Jakarta, I was hanging out with Bang Rohim, the head of the neighbourhood association in the area. We walked past the motorcycle’s parking area that illegally occupied the sidewalk on the main street. The parking area was guarded by a local youth in his mid-20s, who had a tattoo on his arm, and his red eyes indicated that he looked drunk. The man wore a black t-shirt an image of IB-HRS (which stands for Imam Besar Habib Rizieq Shihab) and the writing ‘let's join the revolusi akhlak (moral revolution) with the grand imam of HRS’. Intrigued by what I just saw, I asked Bang Rohim why a figure like Habib Rizieq was so popular among locals. Bang Rohim replied:

'I am not sure why, but maybe because habib (Rizieq Shihab) is the only figure who can speaking up against injustice experienced by people in their everyday life. For habib, all residents welcomed his return to Tanah Abang. In this neighborhood, even though the youth here still drink alcohol and violate other Islamic prohibitions, but if the habib is being harassed, they will defend him at all costs. You know Usman and Yahya (both local youths), right? They joined different ormas (society organisations), but they rented a car and went to the airport to welcome habib from Mecca. They basically have the same flag: the flag of the habib.’

Like other communities in Jakarta's lower-class neighbourhoods, many youths in Tanah Abang participate in and range of associations, from ethnic and nationalist ormas (organisasi masyarakat, social organisation) to dhikr majlis or prayer groups led by prominent habaib and preachers. In this neighbourhood, I saw the t-shirt of ‘grand imam of IB-HRS’ worn by both a local ormas youth who guards illegal parking areas, and also by a pious and unemployed youth who is involved in majlis and organises mosque activities. Neither man is a member of the FPI. From spending hours with them, I have come to realise that you do not need to be 'radicalised' and 'militant' to have sympathy with Habib Rizieq. But why do they adopt Habib Rizieq as a hero?

Rebel with a cause

Bang Rohim's remarks might explain why many urban Betawi youths in the area are sympathetic to Habib Rizieq. His allure and that of FPI among many urban Betawi (poor) youths, could be traced back to the sense of marginalisation and frustration over socio-economic problems such as unemployment, displacement, and lack of social recognition. Once considered the landowners in Jakarta, the Betawi residents are increasingly pushed to the margins of society as the result of uneven urban development and its concomitant displacement. The current generation of Betawi youth have largely resorted to working in the informal economy to make ends meet; they work as ojek (motor taxi driver), store attendants, parking rangers, office boys, and security guards.

These urban precariat youth identify Habib Rizieq as an anti-establishment, revolutionary and rebel figure, who stands with the marginalised and oppressed people. Perhaps like the global youth who embrace the iconic image of Che Guevara —a leading figure of the Cuban revolution— as a cool way to symbolise the spirit of resistance and rebelliousness, Jakarta's poor youth use the t-shirt of Habib Rizieq to articulate grievance and struggle against injustice and marginalisation encountered in everyday life. The state's campaign to repress FPI and the absence of a viable opposition to the government, serves to reinforce Habib Rizieq’s reputation as a resistance figure.

While many have tried to explain the prominence of Habib Rizieq and FPI in terms of growing conservatism and intolerance among the (urban) Muslim community, the appeal of such a figure lies in the feelings of insecurity and marginalisation that many urban poor in Jakarta experience everyday.

Zaki Arrobi is a PhD researcher at the Department of Cultural Anthropology, Utrecht University, the Netherlands, and a lecturer at the Department of Sociology, Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia.