The story of a senior officer in the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (KNIL), and of his oldest daughter, give voice to Moluccan experiences in colonial history

Huib Akihary

Petrus Akihary was born in 1908 in the village of Aboru, on the island of Haruku in the Moluccas. He was a sergeant major instructor in the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (KNIL). His eldest daughter Martha Anthony-Akihary was born in 1936 in Sigli, Sumatra, and now lives in Maarssen in the Netherlands. Their stories were among those included in the exhibition ‘Revolusi! Indonesia Independent’ at the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam (11 February–6 June 2022).

The exhibition features eyewitnesses accounts of Indonesia’s struggle for independence in the years 1945–1949. Their stories are illustrated by more than 200 objects selected from the eyewitnesses’ private property and from art collections in the Netherlands and Indonesia. The composition of the exhibition, and the selection of the eyewitnesses and objects were in the hands of a team of curators from the Netherlands (Rijksmuseum) and Indonesia.

In the summer of 2021, the curators of the Rijksmuseum approached me in my role as curator of the Moluccan Historical Museum, asking for a suggestion for a Moluccan story or perspective that could serve as part of the exhibition. From a number of options, I chose the easiest, and also one that was closest to me: the story of my own grandfather, a KNIL soldier, Petrus Akihary. His was illustrative of the story of the Moluccan professional soldier who signed up for the KNIL, not so much for political reasons as to ensure a secure income for him and his family.

A soldier’s journey

In 1928 at the age of 20 years, my grandfather voluntarily registered with the KNIL in Ambon. He was assigned as a fusilier in Ambarawa, Central Java, and my grandmother, aged 18-years-old, joined him. In the following years, my grandfather was transferred several times: to Malang, Surabaya, Sigli, Magelang, again Surabaya and finally Medan. Grandmother and their growing number of children followed. In 1941, Akihary was stationed in Medan and promoted to sergeant. During the Japanese occupation from 1942–1945, he was a prisoner of war in Medan, then Singapore, Bangkok and again Sumatra. After the war, he reported to Fort de Kock, now Bukittinggi, and was stationed in Sabang, Aceh province, on the northernmost tip of Sumatra. In the rank of sergeant major instructor, as an experienced weapons specialist, he trained young Dutch conscripts who had been sent to Indonesia. In 1949, Akihary was responsible for guarding captured Acehnese who fought on the side of the Republic.

On 27 December 1949 the Netherlands recognised the sovereignty of the Republic of Indonesia. The KNIL had to be disbanded no later than 26 July 1950, resulting in the demobilisation of all indigenous troops at their place of choice, or transfer to the Indonesian army. A large number of the Moluccan military wanted to return to the Moluccas, including Akihary, however, after the Free Republic of the South Moluccas was proclaimed in Ambon on 25 April 1950, the Moluccas was no longer negotiable as a place for demobilisation. At the beginning of 1951, temporarily sending the Moluccan ex-KNIL soldiers to the Netherlands seemed to be the only solution for the Dutch administration. On 12 May 1951, Petrus Akihary and his family arrived in Amsterdam by boat.

A promise

My choice to propose my grandfather as a representative for the Moluccan section of the ‘Revolusi!’ exhibition also had a personal reason. In 1981–1982, I did an internship at the Rijksmuseum’s Dutch History department and contributed to the composition of the exhibition ‘Vesting’, on four centuries of fortification in the Netherlands. Two days after the exhibition opened, grandma Akihary died. In Culemborg, where my grandparents lived, the family sat together in mourning. Grandpa had locked himself in the bedroom. He opened the door for me. ‘Tutup pintu’, he said. ‘Close the door again.’ On the bed were photos of Ambon, of grandma, of the children and of him as a sergeant major instructor in Sabang. That evening he told me about grandma, the war, his imprisonment, his time in Sabang as a soldier, the offer to become a senior officer in the Indonesian army and his refusal, coming to the Netherlands and his faith in God.

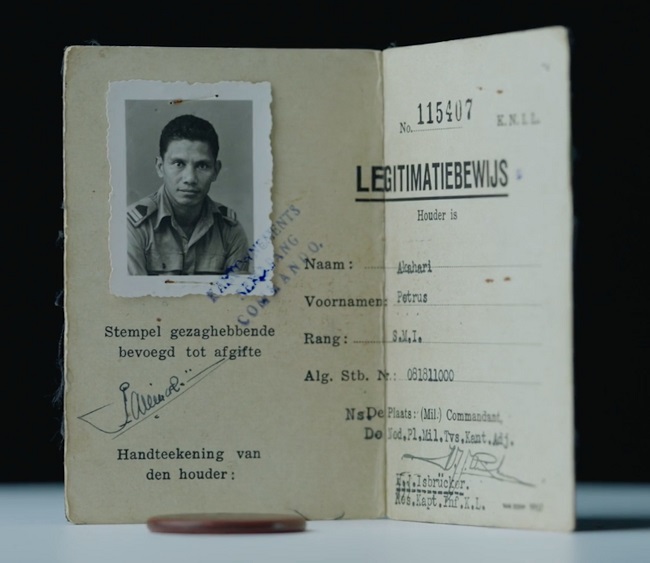

A few weeks after grandma’s death, grandpa came to see my exhibition in the Rijksmuseum and he met curator Bas Kist, who was himself born in Batavia in 1933. The two talked a lot about the Indies, weapons and the KNIL. ‘The KNIL and the role of the Moluccan soldiers, demobilisation and decolonisation will one day have to be the subject of an exhibition in the Rijksmuseum,’ said Bas Kist. It sounded like a promise and with the Revolusi! exhibition, the Rijksmuseum seemed to be fulfilling that promise forty years later. The curators of the Rijksmuseum agreed with my suggestion to include the story of Petrus Akihary, especially when I told them that the family owns two special personal objects: a KNIL identity card and a metal body tag with name and studbook number.

From attic to museum

When I was asked to contribute to ‘Revolusi!’, I brought the news to my aunt Martha. I explained to her that the Rijksmuseum also wanted to show a Moluccan perspective, ‘a personal story supported by one or two privately owned objects’. I tell her: ‘I would like to propose grandpa Petrus as the Moluccan representation. Grandpa stands for the Moluccan soldiers who were employed by the KNIL in 1945–1949, some of whom were even interned during the war years 1942–1945, and more than 3500 were finally taken to the Netherlands in 1951.’

After his death in 2000, grandpa Akihary’s personal belongings came under the care of his daughter, my oldest aunt, Martha Anthony-Akihary. Grandpa instructed her to take good care of his personal belongings, which included some very interesting objects: photos of him in KNIL uniform, military awards, decorations, a KNIL identity card and a metal body tag with a studbook number stamped into it. I wanted to include the last two objects in the exhibition to accompany my grandfather’s story.

I ask Aunt Martha if she wanted to loan these two objects for the exhibition. Her answer is firm. ‘No, those things will not leave the house. The museum can take pictures of the objects, but I will not lend them.’ She adds, ‘Besides, I don’t even know exactly where those things are. Somewhere in the attic.’ I was utterly surprised by her resolute answer. But I would not give up.

I explained to my aunt how a loan works and that the Rijksmuseum, as a borrower, will devote all due care and attention to the loan, including providing door-to-door insurance, specialised transport and an official loan agreement in which all particular wishes of the lender are neatly recorded. I also tell her that the story of grandpa and our family is illustrative of the 3500 Moluccan KNIL soldiers and their families who, following the Netherlands’ recognition of the sovereignty of the new Republic of Indonesia in 1949, had to demobilise and finally in the spring of 1951 were sent to the Netherlands in anticipation of a permanent solution. Aunt stuck to her decision: ‘No, I will not lend the stuff.’

I ask my youngest aunt for help to convince her older sister that nothing will happen to the objects. That the loan is in safe hands with the Rijksmuseum. A few days later I visit aunt Martha again to explain everything and convince her that by lending the objects she can give her father a beautiful tribute at the museum, and that the story and the objects will also be included in the exhibition catalogue. Aunt finally agrees, under one condition. The loans must be returned to her before 11 June, grandpa’s birthday. The Rijksmuseum found this requirement very special and agreed to include it in the loan agreement.

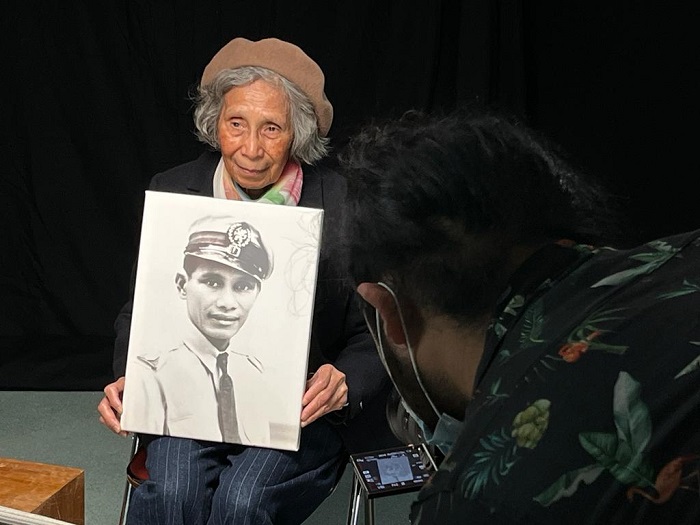

Video portrait of daughter Martha

When Martha Anthony-Akihary finally agreed to lend her father’s objects, she did not realise that she herself would take pride of place in the exhibition. Beyond Walls, a collective of historians and curators led by Suzanne Rastovac, had been commissioned by the Rijksmuseum to create a series of promotion films for the Revolusi! exhibition. The project evolved to become ten video portraits of eyewitnesses, including aunt Martha, who tell their stories about how the revolution impacted their lives. After seeing the portraits, the director of the Rijksmuseum Taco Dibbets said they were so moving and powerful that they would make a magnificent closing piece of the exhibition. It was a masterful move, for which I salute Beyond Walls and the Rijksmuseum. Now the story of both Petrus Akihary, and that of his oldest daughter Martha Anthony-Akihary, were present to give face and voice to Moluccan experiences in colonial and postcolonial history.

In her video portrait, Martha Anthony-Akihary recounts how after so many years of separation, in 1946 aged 9-years-old she is reunited with her father She ends her story with her lasting impression of her father: ‘He was a strict father, but a loving man. He meant well with all his children. And he wanted all of us to become more in life than he had achieved’. Martha recalls that he dissuaded his children to follow his footsteps: ‘Don’t join the army. Go ahead and study well so that you can get a good job later. That was Father’s message. Look ahead, make something of your life. At least that’s what I learned from my dad. Don’t mourn but act!’

Huib Akihary, grandson of Petrus Akihary, is curator at the Moluks Historisch Museum in The Hague, the Netherlands. He wishes to thank aunt Martha for letting him tell the story of Petrus Akihary.