Because experience cannot be delegated

Versi Bh Indonesia

Eka Handriana

I am the victim of a housing development. Floods continually sweep over the streets of the block where I live. They come from upstream, which is increasingly built over. Landslides caused by water coming down from the ever more denuded hills have wrecked the foundations of several of my neighbours’ houses. This block is part of a housing complex built with permission from the Semarang City Administration, based on a land-use plan agreed by legislators as representatives of urban citizens. But every time citizens from this block report environmental housing problems to the city government – since the developers will not respond to complaints – they return empty-handed. The government says it cannot do anything. The reason being that the developers have not yet handed them management of the public facilities. My neighbours and I don’t know whom else we should talk to. We face a future with escalating costs, since we have to fix the flooding devastation ourselves.

My story is just one of similar countless others. Once I drove about 40 kilometres from my home to meet someone in the village of Gemulak, Subdistrict Sayung, District of Demak. He told me he and 200 other families were forced to move from their previous place of residence in Kampung Mondoliko, Bedono Village, in the same subdistrict. Their houses, land, rice fields, prawn ponds, and the kampung access roads had sunk beneath the waters of the Java Sea to the north. In the space of two decades, the Mondoliko houses had collapsed.

A group of activists called the Semarang Demak Coastal Coalition (Koalisi Pesisir Semarang Demak - KPSD) has published an ethnography based on interviews with citizens in Sayung. Titled 'Maleh Dadi Segoro', which means 'Becoming a Sea' in Javanese, it shows that this coastal region began to sink after Semarang City began major reclamation projects in the 1990s. They were at Marina Beach, the Tanjung Mas Harbour, and the Terboyo Industrial Estate. The first to sink were two villages close to Semarang City, namely Tambaksari and Rejosari (also known as Senik). The Demak District Government relocated the residents to new land within the irrigated belt near the Demak-Semarang main road. The new kampungs are known as Gemulak, Sidogemah and Purwosari. Naturally this new land was not theirs to own, which meant that they were not compensated for the land, rice fields and prawn ponds they had lost. Meanwhile the next kampung forced to relocate, because it had sunk, received no government support whatsoever.

The same situation happened, with the land collapsing there too. A Gemulak resident showed me his porch, which was being lapped by the salt water. He told me that even if he raised the house by building up the earthen floor, it would still collapse over time, as he had tried that at Mondoliko, with his house collapsing each time he tried this. Yet the road into his new residence was much higher than the floor of his house. Apparently government funding was easily available for raising the road, but not for providing solutions to people in his situation. Like me, he did not know to whom he should turn. He faced a relentlessly high cost of living, from purchasing a new house to continually having to repair it due to the saltwater floods.

Situated knowledge

The problems we face constitute a socio-ecological crisis – a situation of cascading suffering caused by the close connection between human and non-human elements. Both this Gemulak resident and I understand the environment in which we live. I experience floods, I can see where the water comes from and where it goes, and can hear the sound of a massive riverine flash flood. Someone from Gemulak could see the seawater coming into his old home in Mondoliko, and know what it felt like to drag his feet through the water on the submerged kampung road – unable to walk without stepping in water. He knows what it is like to suffer the financial loss of continually raising the floor and the walls, knows how it feels to be afraid each day because the new house he bought in Gemulak has the same problem.

The feminist Donna Haraway uses the phrase situated knowledge to describe an object of knowledge that is no longer a screen or a resource – no longer an object that stands outside the subject who is learning or researching. Instead, the object of knowledge is itself an actor that can experience things; is itself an agent. My experience and that of this person in Gemulak are examples of such situated knowledge. Not knowledge, moreover, that is isolated within an individual, but shaped within a community in a certain situation.

Such forms of knowledge are rarely recognised, for example, in governmental decisions. When it sees floods in my kampung, or tidal flooding in Sayung, the government makes no use of the knowledge situated in those places. The eco-social knowledge, about the water coming down from upstream increasingly built over, and about the house that continually collapses, no matter how often the floor is raised, cannot be converted into solutions that allow people to live safely. Stopping further building further upstream in the river would help, as would stopping the reclamation of coastal land that actually exacerbates the subsidence, the abrasion and the tidal flooding. But these are not the choices of the government. The situated knowledge of the local community is not absorbed by the local parliamentarians sitting in the legislative assembly, and therefore it does not part of the formula for guiding the executive. The voices of most people like us are silenced, unable to find expression.

Instead, the government relies wholly on knowledge that comes from outside our community, which views flash flooding and the tidal flooding, known locally as ‘rob’, as purely an effect of extreme weather caused by climate change. Unlike the voices of most of the residents, voices from outside immediately find a receptive audience and produce policy. Ironically, these policies inspired by outside voices become 'solutions' for the places where we live. The government solution for our place is to build a reservoir, and to 'normalise' the river course so it can cope with increased rainfall during extreme weather events. In addition, they are building a wall (part of a toll road) to keep out rising seawater resulting from climate change.

This situation reflects the dysfunctionality of the representative system in our Indonesian democracy. There is no participation by most residents in environmental politics. Ordinary citizens are not emancipated enough to determine the kind of environment in which they need to live. In a representative democracy, the politics of citizens are colonised by politicians through political parties, the legislative assembly and the executive branch. There is no eco-social justice. Most residents suffer one thing after another as a result of this socio-ecological crisis.

The socio-ecological crisis suffered by most residents is a result of a masculine pattern of development. Non-humans are separated and placed on a lower rung of the hierarchy so they can be subjugated, under the capitalist mode of production. Indeed, the socio-ecological crisis becomes an opportunity to expand capitalism. In the example above, the flooding crisis caused by deforestation due to excessive building, was solved by more building – specifically of a reservoir – the aim of which was to promote more capitalist accumulation. Yet my place is still flooded! The collapse of residential areas caused by coastal reclamation for an industrial estate is again solved by another development project – a toll road and seawall designed to accelerate the circulation of industrial goods. A Mondoliko resident forced to relocate because his house had sunk is still faced with sinking in Gemulak, which used to be dry.

Representative democracy in Indonesia is just an elite democracy, from the elite, by the elite, and for the elite. It run by a political elite that only listens to voices from the elite bourgeoisie, owners of the means of production, to determine what kind of environment will be most profitable for them, even if it disadvantages most ordinary residents. Representative democracy cannot resolve the crisis most people experience, but continually creates new crises.

Eco-social democracy

In a representative democracy, the majority of ordinary citizens run into a dead-end every time they try to voice their objections to decisions that cause them to endure crisis upon crisis. The meaning of democracy itself is narrowed merely to a general election once in five years, with politics becoming restricted to electoral politics. Participating in politics is just joining a political party or becoming a government official. There is never any discussion about citizen politics.

The ecologist Murray Bookchin wrote that, before the rise of the nation-state, politics was the activities of citizens in political institutions that they ran themselves on a participatory basis. He is quoted in a book by Janet Beihl, also an ecological writer, entitled The Politics of Social Ecology – Libertarian Municipalism. In the middle of the fifth century BC, citizens of the polis of Athens practised direct democracy through popular council meetings that they held nearly every week to solve their problems by themselves. This gave 'politics' a much wider meaning, with democracy happening continually, every day, not once every five years. Only men took part in these councils – Athenian direct democracy was not ideal. Yet by such means problems were understood directly, being continually refashioned in dialectical ways to approach the ideal.

Bookchin’s ideas of direct democracy were discussed at meetings of the Semarang City Farmers Union (Serikat Tani Kota Semarang - STKS). This group of citizens engaged in agriculture was active during the COVID-19 pandemic from May 2020 until the end of 2021. They saw direct democracy as an opportunity to create space for the majority of ordinary citizens to let their voices be heard politically and democratically, not in a centralised and bureaucratic way.

STKS formulated a number of principles.

- First, to form people’s councils as direct social democratic ecological units.

- Second, to create a confederation of people’s councils.

- Third, to reduce the authority of representatives within the people’s council; citizens had the right to withdraw the mandate of any representative of the council who failed to convey their aspirations.

- Fourth, decisions were in the hands of the people, where the people’s council and the confederation of councils merely had an administrative character and not a decision-making role.

The idea of socio-ecological unit is important here. The most fundamental principle of social ecology Bookchin formulated in his book The Philosophy of Social ecology: Essays on Dialectical Naturalism is that ecological problems, in the end, are social problems. The two stand in relation to each other as humans and non-humans – always interconnected. In social ecology, relations among humans, and relations between humans and non-humans, are on the same level. Humans are a part of nature, just as nature constitutes humanity. STKS described direct democracy within a social-ecological unit, where these relations are on the same level and interconnected, as social ecological democracy. Every citizen is emancipated, and can participate in citizen politics on a basis of equality. There are no elites within the unit.

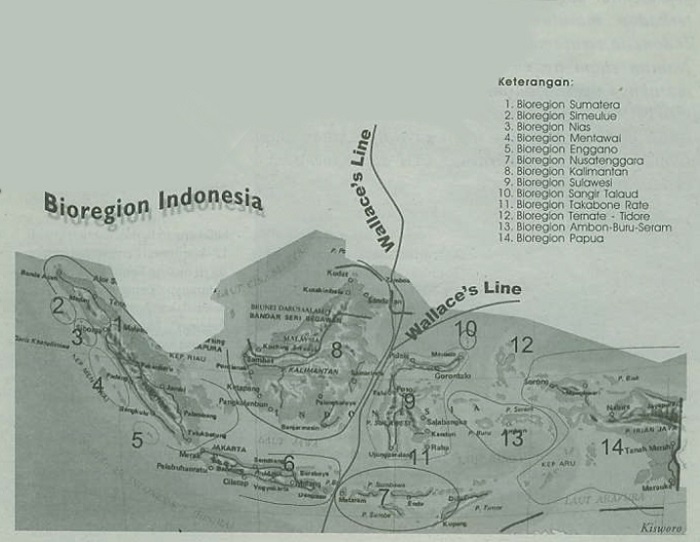

A bioregion is an area where boundaries are determined by its topograhical and biological features, whether it be mountainous or riverine. Political boundaries in a bioregion are not administrative boundaries set by the government, but adjusted to the boundaries of ecology and culture. For example the North Kendeng Mountains are a bioregion. This a hilly region of karst with caves and springs that are used for agriculture by the residents. The region overlaps with a number of administrative districts, running from the districts of Kudus in Central Java to Tuban in East Java. Another example is the Garang River Basin, where my housing complex is located. The region is traversed by the Garang River (Kali Garang) and its tributaries, and runs from the headwaters on Ungaran Mountain in Semarang District, to the mouth of the river in Semarang City.

'Bioregionalists' are people who use the bioregion to look for solutions to the problems they face. Janet Beihl in her social-ecological writings often talks about the calls of the bioregionalists for an alternative society. The alternative community they have in mind differs from society today with all its economic competitiveness, its commodification, and its artificial 'needs'. Bioregionalists, according to Beihl, are calling for decentralisation, where habitats are built more simply at the local level and become as autonomous as possible. They will build local factories with simple tools, establish local cooperatives to meet their needs of food, growing as much as possible themselves, and replacing money with barter. She says that bioregionalists promote a simple lifestyle, letting go of consumerist patterns that can never be satisfied, reducing their possessions, and reshaping themselves as members of a local ecology where humans are part of nature, directly and physically touching the air and the soil. They reject technology that risks destroying nature, promote a drastic reduction in consumption for people in extremely wealthy countries, and spurn the technological basis of economic productivity.

Some of these calls appear to be difficult to achieve, not to say utopian, at the present moment. Yet the environmental group WALHI already in 2001 was calling for 'Bioregion, return to the grassroots', in its journal Tanah Air. If a bioregion with direct democracy became a reality in my home, my voice as a citizen and a resident of Gemulak would be heard in all the decisions we took ourselves to determine our environment, the place where we live.

Eka Handriana (handrianae@gmail.com) is a writer who lives in Semarang. She is grateful to STKS for permission to quote from its publication about social-ecological democracy.