Indonesia–Australia educational exchange from an Indonesian perspective

Ratih Indraswari & Sylvia Yazid

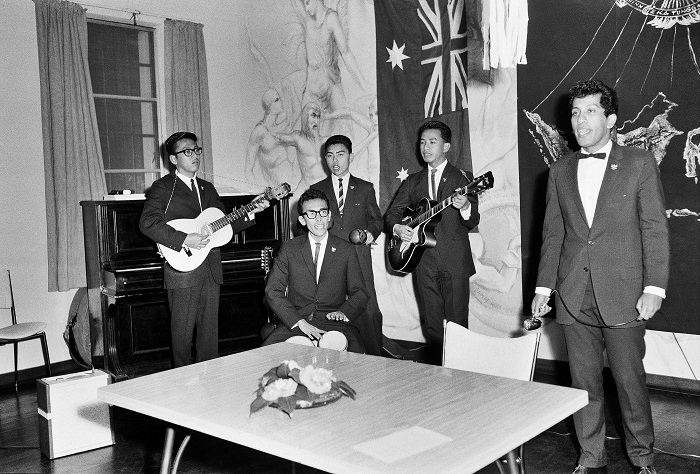

Indonesia and Australia have enjoyed nearly 70 years of educational exchange since 1953 when the first cohort of Indonesian Colombo Plan recipients arrived in Australia. What began as a politically endorsed aid program during the Cold War has sustained over time and transformed into a range of Indonesia–Australia educational exchanges varying in duration, location and academic discipline.

In recent decades, Australian students have been studying abroad in increasing numbers, including in Indonesia. In 1998, around 3,375 Australian students took part in a learning abroad program and, by 2019, this number had increased more than 200 per cent to 58,058 students. A significant driver in this growth was the launch of the Australian Government’s grants and scholarship scheme – the New Colombo Plan (NCP). Launched in 2014, the NCP further cemented the importance of student mobility and offered Australian students the opportunity to experience in-country study in the Indo–Pacific region, including in Indonesia. By 2019, the Indo–Pacific region accounted for up to 45 per cent of all Australian learning abroad experiences, with one in two taking a learning abroad program here in Indonesia.

A report from the AUIDF in 2019 shows that Australian students’ preferences for study experiences range from faculty-led study tours (22%) to internship / practical placements (20%), summer or winter programs at a host university (16%) and full exchange programs (15%). The first three types of study experiences require a shorter period of time in comparison to semester-based exchange programs. This indicates a strong preference among students for short-term programs. Similarly, 90 per cent of students undertaking NCP programs in Indonesia have preferred to enrol in programs for less than 10 weeks’ duration, with only 10 per cent taking on a full semester or longer.

The NCP has proved an effective and popular framework through which students can enrol in Indonesian Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), as study is undertaken for credit towards students’ home degrees in Australia. While the Indonesian government has attempted to draw foreign students to Indonesia through similar schemes, such as the Darmasiswa Scholarship (a long-term cultural exchange program), or through short-term Indonesian Arts and Cultural programs from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA), neither program attracts significant numbers of students as they are non-credit bearing. In the past five years, for example, only 27 Australian students have enrolled in the Darmasiswa program. University-to-university bilateral programs have also illustrated some patterns of mobility between Indonesia and Australia; however, these are often scattered, sporadic and ad-hoc, and often depend on individual HEI networks and connections to attract students and drive mobility. Overall, there has been a lack of consistency and structure in Indonesian HEIs’ approach to internationalisation.

From soft power to 'skilling-up'

The Indonesian government recognises the importance of international education as a tool of public diplomacy and soft power. As stated in the MoFA 2015–2019 strategic plan, public diplomacy is highlighted as a priority area to increase Indonesia’s role and influence internationally. The focus on international education is further elaborated through the strategies of the 3rd Policy Direction which emphasise the ‘utilisation of public diplomacy … through cultural cooperation, scholarship, people-to-people contact …’ (MoFA, 2019).

At the end of 2020, the Public Diplomacy Directorate of the MoFA made a targeted effort to better understand Indonesia’s soft power capacity through a series of Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) involving more than 600 experts, practitioners and academics. These FGDs took a ‘bottom up’ approach in identifying and mapping grassroots opinions on who or what actually constitutes ‘soft power assets’. The results confirm the efficacy of international education as a stable and durable instrument of public diplomacy. In fact, activities such as student mobility (both inbound and outbound) as well government scholarships for international education activities have received attention widely. As a result, the Indonesian government has continued to prioritise these approaches as a means of boosting Indonesia’s international cooperation, particularly at the bilateral level.

The Indonesian Ministry of Education (MoE) acknowledges the value of international education in producing global graduates, developing staff competency and increasing the overall academic quality of Indonesian HEIs. These indicators can also be seen in global ranking systems and are mirrored nationally through Indonesia’s national university ranking system. As a result, many Indonesian HEIs have also begun to include similar internationalisation targets in their own respective institutional performance metrics, with a goal of moving towards more ‘international’ learning and teaching environments. HEIs notably have launched myriad internationalisation activities in response to this trend. To increase the number of foreign students, the Indonesian MoE has introduced policies to strengthen the institutional capacity of university international offices through PKKUI (Penguatan Kelembagaan Kantor Urusan Internasional) grants.

These grants support universities to deliver short-term programs aimed at increasing the number of in-country study programs for international students in Indonesia, complementing long-term government scholarships such as the Darmasiswa program and the Kemitraan Negara Berkembang (or KNB, ‘Developing Country Partnership Scholarships’) which support students from developing countries). Similarly, the Indonesian MoE has recently launched the ‘Merdeka Belajar – Kampus Merdeka’ (‘Independent Campus, Freedom to Learn’) or ‘MBKM’ program, which includes the Indonesian International Student Mobility Awards, offering a semester of funding for Indonesian students to study at top ranked universities in various countries, including Australia. Although the 2021 student intake might still be deferred by closed international borders, the participation of a number of Australian universities in this program, and MoE’s support for it, demonstrates a clear willingness among Australian and Indonesian universities to to ensure continued collaboration.

These programs demonstrate that the Indonesian government takes seriously its commitment to internationalising higher education, incorporating both inbound and outbound aspects for international and Indonesian students. Yet, as in other parts of the world, COVID-19 has had a profound effect on international education in Indonesia, presenting a range of new challenges for the government and HEIs to overcome.

Adjusting the strategy

Most notably, with the cessation of physical travel and learning abroad, COVID-19 has altered a ‘business as usual’ mentality in Indonesian’s higher education internationalisation strategy. Many HEIs have begun adopting virtual delivery modes for their learning abroad programs, and pivoting to online delivery for learning and teaching. But how are students responding to this shift?

When we spoke with Indonesian students at the Parahyangan Catholic University in Bandung, we noticed two opposing trends in their responses. In one camp were students who noted that if mobility programs switched to an online delivery mode they would no longer be interested in participating, as their sole motivation had been to travel abroad. In contrast, other students did not seem fazed by the online pivot and noted that they still wanted to participate as they felt the online interaction would build useful intercultural capabilities and global citizenship skillsets.

These differing viewpoints highlight the need for Indonesian HEIs to reflect on their current internationalisation strategies in the wake of the pandemic. For semester-based programs, many have switched to online programs supported by funding made available from the MoE. The MoE responded swiftly to the pandemic by funding a shift in international programs from physical delivery to virtual delivery, and they have also been encouraging online learning through initiatives such as the Indonesian Online Learning System (SPADA). At the end of March 2021, the Indonesian and Australian governments conducted a virtual online higher education policy dialogue, with the theme of ‘Delivering online learning and using appropriate technologies’. Additionally, as cultural and ‘travelling’ experiences have been major elements of Indonesian universities’ international programs, there have been efforts to transfer these experiences to virtual delivery using virtual reality (VR) technologies.

After COVID-19

At present, higher education providers are still struggling with the uncertainty caused by the pandemic. As for higher education internationalisation, the strategy seems to be divided into two orientations: short-term and long-term.

A short-term strategy is heavily characterised by a race toward shifting almost all interactions and activities to virtual delivery: online classes, collaborative online international learning, virtual short courses, cultural tours and the like. These short-term aims will most likely give a boost to the understanding and implementation of ‘internationalisation at home’. As explained by Weimer, when it emerged in the 1990s, this concept was understood as internationalising the home education and environment, mostly through curriculum development, so that those who are not involved in international mobility can still develop their international competencies. Before the pandemic, with actual mobility being more interesting and technological development still limited and not prioritised, this internationalisation at home was translated as creating an environment for local students to interact with inbound students. When mobility is halted, the use of technologies as bridges and mediums through virtual activities becomes critical.

In the longer term, although there have been statements that ‘online learning’ may become the new normal or the new ‘face’ of education, it will not completely replace a physically interactive method. Current online learning methods have not been able to completely transfer the ‘sensation’ of being an exchange student abroad. It is more likely that those involved in international education will keep both physical and virtual mobility options open, and this should be viewed as an enriching and complementary approach. While virtual engagements may serve a purpose for the time being, at some point physical mobility will have to be brought back into the picture as students look to travel outside their home universities, to study overseas, intern and volunteer in different sectors, and challenge themselves in different cultural settings. Virtual and physical mobilities can co-exist moving forward if universities adjust their internationalisation strategies accordingly.

While this period of immobility has posed significant challenges for internationalisation within Indonesian HEIs and for Australia–Indonesia educational exchange it also offers many new opportunities for working together. Sharing seminars and online cultural programs with students from Indonesian and Australian universities allows students to maximise their virtual learning despite logistical challenges of poor connections, time differences and language barriers. We have seen over the past year that there is a student appetite for this type of learning, and that they have the technological aptitude for it. While the pandemic has posed significant challenges for teaching and learning in international education, it is also demonstrating that creativity and innovation abound and the desire to forge meaningful bilateral connections remains ever present, whether in physical or virtual delivery.

Ratih Indraswari (indraswari.ratih@gmail.com) is a faculty member in Parahyangan Catholic University, Bandung, and a PhD researcher in Political Science and International Relations at Ehwa Woman’s University, South Korea. Sylvia Yazid (s_yazid@unpar.ac.id) is an Associate Professor at Parahyangan Catholic University and the Head of the Office of International Affairs and Cooperation.