Artists from the famed village of Jelekong are unsure about what the future holds

Ari Adriansyah

After passing through the arch welcoming visitors to the village, dozens of little painting studios and art galleries come into view, extending for about 700 metres along the village’s main street. Paintings in all shapes and sizes are hung outside the buildings and shopfronts, making an engaging sight for the visitor. Painters appear poised as they apply their various methods, manipulating their palette knives, making brush strokes, or smearing paint on their canvases with a sponge. Other people make noise as they bang frames together and stack paintings to be offered for sale at markets outside the village.

This is Jelekong, in the sub-district of Baleendah, Bandung. It lies about 17 kilometres to the east of the centre of Bandung, about 45-60 minutes by road. Positioned under the foot of Mount Geulis, this village has become well known because of a number of enterprises encountered within it. Apart from being known for the community of dalang, or puppetmasters, known as Giri Harja, for its anufacture of rod puppets (wayang golek), and for a number of artistic communities, Jelekong also has a reputation as the ‘painting village’ that supplies most of the paintings exported to other areas of Indonesia.

The pioneer

It was Odin Rohidin (71) who pioneered painting in Jelekong in 1965. Originally a dramatic actor, Odin became interested in painting the backgrounds for stage productions. In 1964 he began to learn painting from his brother-in-law, Wawan, and joined the artistic community known as Planet Senen in Jakarta. After one year studying painting, he returned to his home village.

Since then Odin has applied himself to his own art, while also teaching painting and martial arts to relatives and neighbours. In the beginning he had 12 students, who studied very simple painting techniques using canvas and oil paints. By now, the number of painters has increased, and their range of techniques has expanded also. Out of the nearly 5000 people making up Jelekong’s population, 35 per cent are painters. The village’s productive painters include artists aged as young as 10 and as old as 55, and count amongst them the well-known painter Hendra Gunawan.

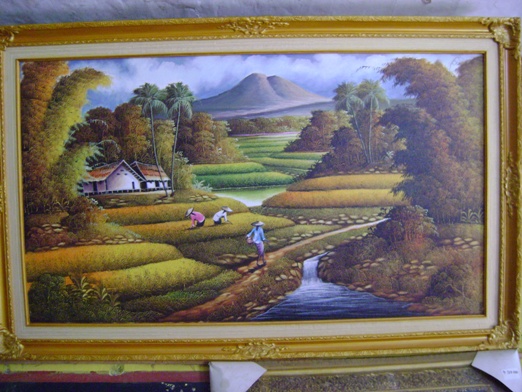

Jelekong’s painters can handle a range of subjects that find favour with buyers around Indonesia Ari Adriansyah

On average, one person can produce 10 to 20 pictures per day. Mostly, the artist already knows well the painting’s images in advance, having painted them many times in the past, though this is not the case with specific commissions or new creations. These need longer time. Nowadays, Odin himself rarely paints, because of frequent poor health. ‘Nowadays, painting is for the young ones. The old people just give inspiration. I will paint if I receive an order. But even then I don’t have the strength to do it for long, for my eyesight is not clear, and I no longer have much strength,’ he said.

Jelekong has become well-known for its paintings in the naturalistic style, especially landscapes. In the 1980s many variations of this theme were produced in the village, as well as scenes from daily life, animals, plants, calligraphy, abstracts and many others. But even today landscapes remain the compulsory subject matter for all of Jelekong’s painters. Painting techniques have also developed beyond the most basic ones to include brush effects, scrubbing, knife palate and sponge techniques.

Jelekong of today

Jelekong paintings are not expensive. The most costly are normally between one and six million rupiah (AU$100-600), and nothing will ever be over Rp.10,000,000 (approx. AU$1,000). The price of a painting depends on it size, materials, techniques and quality. Most of the expensive ones use the knife palate technique (relief painting). Size does not always make a difference, for some larger ones (ie 130 x 70 centimetres or more) might cost only Rp.35,000 because they use the sponge technique.

A painting as small as 40 x 60 centimetres made with the palate knife technique might cost as much as Rp.1,000,000. A painting on canvas made with brush effects could come in anywhere between Rp.100,000 ($AU10) and Rp.5,000,000 (AU$500).

The village’s paintings are marketed domestically in Java, Bali, Sumatra, Kalimantan and Sulawesi. But the majority go overseas, to Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore, China, India and Saudi Arabia. Those sold within West Java can be found on the market in Bandung’s Braga Street, Bogor and Cianjur. Some people sell the paintings door-to-door in Bandung. Quite a few Jelekong painters have participated in exhibitions in Berlin, Germany, the Netherlands, Dubai and other countries in the Middle East. Some Jelekong painters who have gone to Arab countries as contract workers have become ‘local painters’ in those countries.

Landscapes are a stock theme for Jelekong’s artists Ari Adriansyah

But in current times, the life of Jelekong painters is not as beautiful as their paintings. For a number of reasons - the poor economic situation, rising costs of equipment and materials, competition with other painting centres, a passive attitude to promotion and publicity, and a lack of assistance from the government – many Jelekong artists have changed their line of work. The village’s marketing has always relied on the efforts of individuals, and has failed to take advantage of the potential of art exhibitions. It has also failed to take advantage of the tourists who come specifically to the village, but whose times of arrival are not known in advance.

The national market for paintings is not working in the village’s favour. Not long ago, Jelekong painters did good business by undercutting the paintings produced and sold in the tourist markets of Ubud and Sukawati. But Jelekong is not the only village supplying such artworks to Indonesian and foreign buyers, and the resultant flooding of the market has pushed prices down.

The government has plans to make Jelekong into a ‘Tourism and Cultural Village’, and the village has received concrete benefits out of this plan. In a visit in December of 2012, the governor of West Java, Ahmad Heryawan, granted assistance for the completion of a studio and performance space for the Giri Harja puppetry group, something which will benefit the village widely. The painters, however, are still waiting for help.

If well-executed, the village’s outstanding potential could make it a profitable centre for artistic production in West Java. But today Jelekong’s painters are waiting before they decide whether they should stick with painting for the long term, or roll up their canvasses one by one before switching to a more reliable way of earning their livelihoods.

Ari Andriansyah (ariandriansyah40@yahoo.com) is a journalist, writer and teacher of Sundanese language at SMAN 1 Ciampel, Karawang, West Java. This article was originally published in Cupumanik magazine, and was translated from Sundanese by Julian Millie. Inside Indonesia thanks Cupumanik for permission to translate and publish the article.