Succession within the Sultanate of Yogyakarta decides who will own vast tracts of land

Cally Colbron

The current Sultan of Yogyakarta, Sri Sultan Hamengku Buwono (HB) X is the father of five daughters and no sons. The Sultanate has customarily been inherited through the male line. Following that tradition, it was widely assumed that at the end of the current Sultan’s reign the Sultanate would pass to his half-brother. Since the position of Sultan is automatically granted the office of Governor of Yogyakarta Province, this would also mean the Sultan’s half-brother would assume this position.

The privilege of government office without elections is unique to Yogyakarta. It is also a relatively new phenomenon. The current Sultan’s father, Sri Sultan Hamengku Buwono (HB) IX, held the position of Governor of Yogyakarta from the period of Indonesian independence until the time of his death in 1988. However, he had not been entitled to the position by law. The linking of the Yogyakarta governorship to the position of Sultan as an inherited position became national law in 2012.

Gender equality?

On 30 April 2015, Sultan HB X issued a royal proclamation indicating that the position of Sultan could be held by a female. The proclamation also altered the official titles of the Sultan. It removed the Islamic designation ‘Khalifatullah’ (Caliph), a title that can only be held by a male, and replaced the Javanese male designation ‘Buwono’ (loosely translated as ‘universe’) to the gender neutral ‘Bawono’. On 5 May the Sultan issued another decree to change the name of his eldest daughter Gusti Kanjeng Ratu Pembayun (GKR), giving her a new title designating her as the crown princess.

Media coverage and commentary from outside Yogyakarta has widely described both the decree and the proclamation as wins for gender equality. Some have suggested that the dispensing of 'Khalifatullah' from the official title is a step that not only paves the way for a female Sultan, but also strengthens values of religious diversity within Yogyakarta, since it weakens the identification of the Sultanate with Islam. Media commentary within Yogyakarta has centred on expert opinions that the changes are illegal under the terms of the 2012 Yogyakarta Special Region Law (Law No. 13/2012). The 2012 law, by linking the governorship to the Sultan, made the position of governor no longer subject to elections. The 2012 law mentions the position of wife of the Sultan, leading some to argue that this indicates unequivocally that the position of Sultan must be held by a male. After 2012, Sultan HB X lobbied the provincial parliament unsuccessfully to remove the paragraph containing mention of the wife of the Sultan but the stipulation remains. The 2012 law also granted the vice governorship to the Pakualam, head of a small duchy called Kadipaten Pakualaman within Yogyakarta Province. Kadipaten Pakualaman was originally created by British colonial powers with land taken from the Sultanate of Yogyakarta as part of colonial Britain’s divide and conquer approach to maintaining control over the local populace.

Media commentary within Yogyakarta has centred on expert opinions that the changes are illegal under the terms of the 2012 Yogyakarta Special Region Law (Law No. 13/2012). The 2012 law, by linking the governorship to the Sultan, made the position of governor no longer subject to elections. The 2012 law mentions the position of wife of the Sultan, leading some to argue that this indicates unequivocally that the position of Sultan must be held by a male. After 2012, Sultan HB X lobbied the provincial parliament unsuccessfully to remove the paragraph containing mention of the wife of the Sultan but the stipulation remains. The 2012 law also granted the vice governorship to the Pakualam, head of a small duchy called Kadipaten Pakualaman within Yogyakarta Province. Kadipaten Pakualaman was originally created by British colonial powers with land taken from the Sultanate of Yogyakarta as part of colonial Britain’s divide and conquer approach to maintaining control over the local populace.

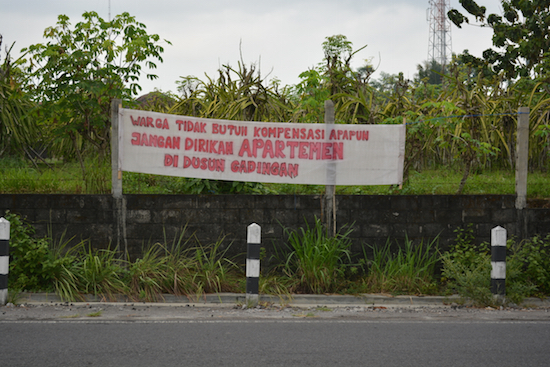

Among the Yogyakarta public, the proposed changes were met with suspicion. Banners popped up throughout Yogyakarta urging a return to the ‘rules’ of the Kraton. Suspicions were aired on social media and other casual commentary as to the motivations behind the changes. Anti-development sentiment has also grown, due to the Sultan’s role in politics and control of land in the region.

Reclaiming land

Yogyakarta has enjoyed a degree of autonomy and ‘special’ status since the colonial era. After independence, that ‘special status’ was entrenched in national law in recognition of the extraordinary role that both the then Sultan (HB IX) and then Pakualam (VII) played in supporting the independence movement. The Sultan and Pakualam retained ownership of land belonging to the Sultanate and Pakualaman, rather than it being taken over by the new state. Traditional ‘royal’ land remained in use by local communities and a great deal was used for public works projects in the manner of public land. These projects were perceived as benefiting the community at large, and ranged from using land for the establishment of a public university to engineering projects.

In 1984, Sri Sultan HB IX adopted the 1960 Basic Agrarian Law (BAL) in Yogyakarta, a move that saw the ownership of all remaining crown land or royal land (owned by the Sultan or Pakualam) being transferred to the Republic of Indonesia. Prior to this, Sri Sultan HB IX had embarked on a range of public works on crown land and the BAL had little effect on this practice. The adoption of the 1960 BAL came after Sri Sultan HB IX’s withdrawal from national politics in 1978, a move precipitated by then President Suharto’s withdrawal of support. From that time until his death in 1988, Sri Sultan HB IX remained Governor of Yogyakarta. Tensions between HB IX and Suharto then transferred to the current Sultan, who was denied appointment as the governor of Yogyakarta until Suharto fell and the position was won by election in 1998.  The 2012 Yogyakarta Special Region Law, which linked the governorship to the Sultanate, was perceived as recognising Yogyakarta’s unique status as the cultural epicenter of Java. It received broad support from a vast majority of Yogyakartans. This law came in the wake of mass protest against a proposition from then President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono that would see regular democratic elections for the position of governor and vice governor of Yogyakarta. Rhetoric surrounding the debate took on a Jakarta versus Yogyakarta aspect.

The 2012 Yogyakarta Special Region Law, which linked the governorship to the Sultanate, was perceived as recognising Yogyakarta’s unique status as the cultural epicenter of Java. It received broad support from a vast majority of Yogyakartans. This law came in the wake of mass protest against a proposition from then President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono that would see regular democratic elections for the position of governor and vice governor of Yogyakarta. Rhetoric surrounding the debate took on a Jakarta versus Yogyakarta aspect.

A component of the law that received limited attention until now is the clause that cancelled the BAL and returned to the colonial era Sultan Grond (SG) and Pakualaman Grond (PAG)..This meant that large tracts of land within Yogyakarta were reclassified as crown land, owned by the Sultan or Pakualam. In the wake of the 2012 law an unprecedented mapping project was initiated, aimed at recording all land ‘belonging’ to the Sultan and Pakualam under SG and PAG. Locals who have had their land ownership paperwork amended as part of the mapping exercise began posting photographs of amendments on social media in the wake of the royal proclamation, linking the mapping initiative and the changes to succession.

In a pattern that began before 2012, various sites throughout Yogyakarta have been claimed by the Sultan and Pakualam under the legitimacy of SG and PAG and earmarked for large-scale commercial projects. Local communities who use these sites have been resisting eviction from land and controversy has plagued each project. The legal legitimacy of SG and PAG rests in the 2012 law, since prior to this the 1960 BAL (recognised in Yogyakarta in 1984) had voided the SG and PAG and meant the Sultan and Pakualam had no ownership rights.

The anti-development movement

Resistance to land claims based on SG and PAG and the struggles against dispossession have been going on for several years in various parts of Yogyakarta. One such dispute in Kulon Progo district has seen farmers clash with authorities over an attempted dispossession to make way for an iron sand mining project in collaboration with an Australian mining company. The resistance has been fierce and spanned a number of years, becoming known as the ‘bertani atau mati’ (farm or die) movement – a play on the independence era slogan of ‘merdeka atau mati’ (independence or die). While these farmers have gained positive attention outside Indonesia, within Yogyakarta media portrayals have depicted them as an opportunistic fringe group, until recently. In fact, many within Yogyakarta accepted the official narrative that such organised resistance was the work of preman (organised criminals) or thugs aiming to milk compensation money from the government. That opinion has changed over time, particularly after the recent royal decree and proclamation.

Yogyakarta has also seen a growing anti-development movement, focused on resistance to urban development. The Jogja Ora Didol movement (Javanese for ‘Jogja is not for sale’) has protested with street art resisting what is seen as unfettered and inequitable development. At the same time, spontaneous expressions of protest and resistance to the rampant building of hotels, apartment blocks and shopping malls has been on the increase in local neighbourhoods.

Throughout Yogyakarta, banners expressing opposition to commercial development projects can be seen in virtually every area. Nonetheless, until now only a minority of activists have drawn attention to the nexus between rampant development and the Sultan and Pakualam’s roles as political office holders, landowners and developers. The royal decree appears to have been a trigger which has brought this previously taboo topic out into the open for discussion by the broader Yogyakarta public.

Suing the Sultan

In an unprecedented move, residents of Kulon Progo facing eviction to make way for another development project, the grand scale international airport, launched legal action against the Sultan for his approval of this project. In this case, there is also uncertainty about land rights. The BAL meant that use of the land by local people was protected, whereas reversion to PAG and SG means land rights within these areas are now uncertain. If the Kulon Progo project proceeds, the implication is that PAG and SG takes precedence.

The residents resisting the Kulon Progo airport project are being represented by a local legal aid organisation famed for advocating social justice. Public opinion on the airport project has shifted, and protesters who were viewed with suspicion just months ago are fast becoming a symbol for all Yogyakartans fed up with rampant development, an attitude sharpened since the royal decree and proclamation. The Kulon Progo court case against the Sultan was successful, and a temporary stay on work has been granted. The court decision in favour of residents coincided with the removal of many banners advocating a return to the ‘rules’ of the Kraton. The Sultan has declared his intention to appeal the case and locals still live in uncertainty.

Although the Sultan’s half-brothers have protested the changes to succession, protest from within the royal family has mostly been muted, and it is difficult to imagine protest from those quarters uniting with communities resisting land possessions, given that many members of the Sultan’s extended family have benefited from property development in Yogyakarta. In the view of many locals, succession staying within the immediate family, rather than going to one of the Sultan’s half-brothers as has traditionally been the case, has undermined one of the checks and balances on the power of the Sultanate. The Sultan has defended the changes to succession by saying that the impetus came in messages from God.

Cally Colbron (callycolbron@msn.com) has a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) from Monash University and has been living in Yogyakarta with her family.