Social media promotes political engagement among youth, but at the expense of accurate information and real-world political effects

Diatyka Widya Permata Yasih and Andi Rahman Alamsyah

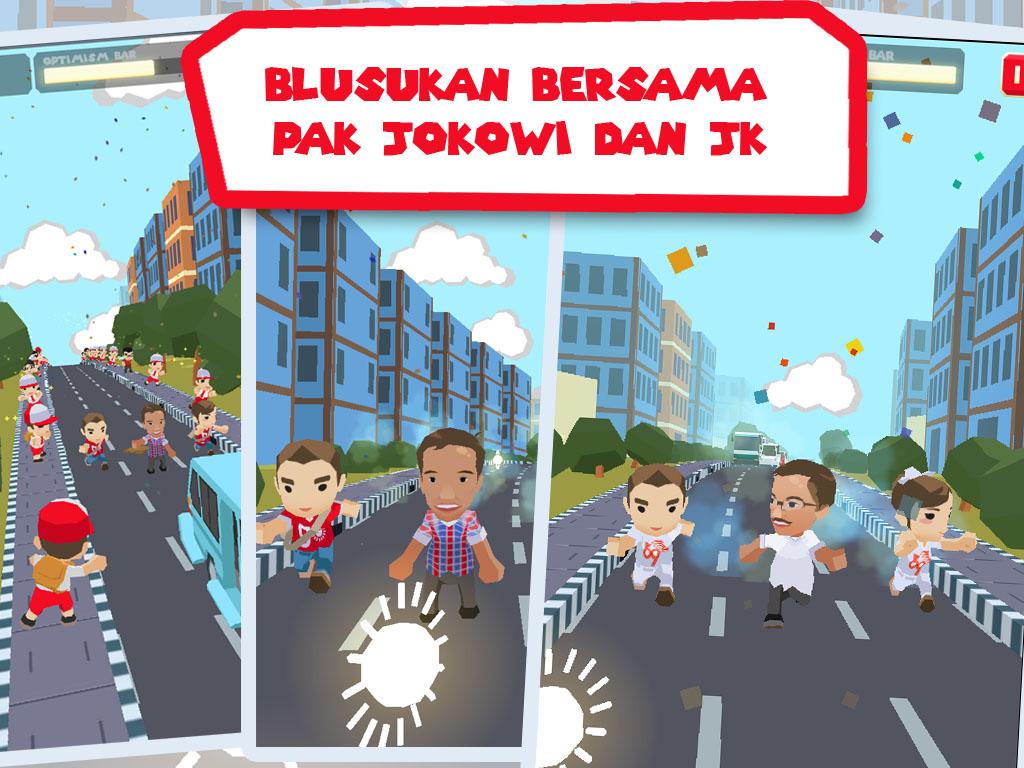

A user-generated computer game developed by Jokowi’s team asks supporters to join Jokowi-Jusuf Kalla on impromptu visits - Generasi OptimisYoung people appear to be heavily reliant on social media to engage in Indonesia’s democratic life. Social media’s momentous sway among young voters was front and centre during the 2012 Jakarta gubernatorial elections, and again during the 2014 presidential elections. Technology-savvy youth took to social media to inform themselves and others on the elections and express their political views, by sharing, co-creating, discussing and modifying user-generated content.

The 2014 elections showed the great potential of web-based and mobile technologies in promoting political education and engagement. However, there seems to be a paradox in the technology-driven politics of youth, as many rely on the abundance of free information circulating online in making their political choices without examining the credibility of the content. Their political activism in the virtual world also appears to have little effect in shaping real-world politics.

Youth, social media, politics

A survey conducted in 2012 by the Indonesian Association of Internet Service Providers (APJII) showed that 58.4 per cent of internet users in Indonesia are between 12 to 34 years old, with those between the ages of 25 and 29 comprising 14.4 per cent. The majority of these young users are highly-educated professionals, followed by high-school and university students. They live in big cities like Jakarta and Surabaya, where adequate infrastructure and internet networks exist. The survey also found that young users mainly access the internet for socialising through social networking sites, with Facebook receiving the greatest number of visitors. YouTube, Twitter and blogs have also become hugely popular among young users, indicating that they are increasingly connected through social media.

Indonesian youth use social media as a flexible instrument to address various social and political issues which allows them to communicate anything, to anyone, from any place, at any time. They use social media to criticise public policies, shame corrupt bureaucrats, highlight social problems, sign online petitions to bring about change, and also organise protest on the streets. This should not come as a surprise: they are at ease in the virtual world, being the first generation to have grown up with the Internet. They also have limited access to traditional political institutions and most feel they have little opportunity to shape the political process. Many are not interested in working through political parties, which remain distant from young voters’ concerns.

In contrast, social media offers opportunities for equal and free participation. Every young person can create, share and exchange political information and ideas, as long as they have internet access. Social media also provides the chance to be part of a national discussion, as youth can interact in virtual communities that reach a wide range of audiences. Thus, in social media, they have found a suitable platform in which they feel they can shape matters that affect their lives. This has not gone by unnoticed by politicians competing for votes; they understand that a carefully managed online presence is one of the keys to electoral success.

Social media as political instrument

The power of social media as a political instrument became apparent during the 2012 gubernatorial elections in Jakarta, when sitting governor Fauzi Bowo was defeated, against the odds, by Joko Widodo or ‘Jokowi’. Jokowi’s supporters created a music video spoof of the boy band One Direction’s song ‘What Makes You Beautiful’, which parodied the many problems in Jakarta and expressed hopes that Jokowi would fix them. The video was uploaded on YouTube and went viral, garnering more than two million views. Although this video can hardly be credited for Jokowi’s victory, it attested to the impact of political messages spread among youth through social media. This became all the more apparent in the 2014 presidential election.

With the population aged between 16 and 30 years old comprising 25.69 per cent of eligible voters, and first-time voters between the ages of 17 and 21 comprising 21.8 million people or 11.7 per cent of the total 186.5 million registered voters, youth formed a significant group in the 2014 legislative and presidential elections. The two presidential candidates—Prabowo and, again, Jokowi—expected to garner the majority of their support from young people, as most of them are swinging voters. Both teams seemed to understand very well that the young are increasingly online. They utilised social media extensively in their campaigns, including Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, mobile games, online radio and other social media applications, seeking to turn digital followers into real-world voters.

Social media as an extension of regular media campaigns served as an instrument to promote positive images of the candidates. Prabowo’s campaign marketed him as a strong and decisive leader, who promised the nation stability, while Jokowi supporters plugged his achievements as Solo mayor and Jakarta governor. The flip side was that social media was also hit with negative and black campaigns. Rumours circulated online that Jokowi, who is a Javanese Muslim, was secretly a Chinese Christian, or even a communist. Meanwhile, Prabowo was mostly attacked for his past, as the perpetrator of human rights abuses related to the abduction of activists and repression of the student movement in 1998 — allegations his supporters say cannot really be proven.

To create the desired online image, Prabowo’s party Gerindra hired a team of young professionals to run his social media campaign. This digital team worked behind the scenes at Gerindra’s headquarter in Ragunan, South Jakarta, taking turns to monitor Gerindra and Prabowo’s online activities 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to respond to questions in real time. Jokowi’s social media campaign was less structured because it was run by volunteers. Still, he proved to be a strong online rival for Prabowo.

These volunteers were mostly technology-savvy university students and office workers who devoted their time and energy to the campaign, building on previous experience in online campaigning for Jokowi. During the 2012 gubernatorial elections, one of the volunteer groups was Jasmev (Jokowi Ahok Social Media Volunteers), which worked to counter negative messages about Jokowi and his running mate. This group also approached public figures who supported Jokowi and lobbied them to demonstrate their support online. For the 2014 presidential elections, the group was revived and renamed Jasmev 2014 (Jokowi Advanced Social Media Volunteers). The loose structure remained, enabling the volunteers in this and other groups to come up with their own unique campaign ideas, mostly targeting youth.

Social media as channel of participation

Social media was used in several ways to engage the youth in the elections. It provided them, in particular first-time voters, with easy access to information and news online through Facebook, Twitter, Path and similar platforms. Since most Indonesian TV networks are owned by political party leaders, whose campaign coverage was partisan, social media was seen as an alternative source of more independent information.

To assist voters in making an informed choice, civil society actors utilised web-based and mobile technologies to provide critical election data. For example, Ayo Vote (Let’s Vote), an non-government organisation (NGO) seeking to improve civic participation among young voters, used its website and social media accounts to provide easy-to-digest electoral information. Other civil society organisations created websites to provide databases of legislative and presidential candidates and recommend candidates with clean records. Among the most prominent was bersih2014.net (clean 2014), initiated by a consortium of NGOs, including ICW (Indonesian Corruption Watch), PSHK (Indonesian Centre for Law and Policy Studies), KONTRAS (Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence), KPA (Consortium for Agrarian Reform) and WALHI (Indonesian Forum for the Environment).

Besides using social media as a source of information, young people also used web-based and mobile technologies to create and share memes, photos, videos and chatter to support their candidate, or attack his rival. A number of hash tags made the rounds. Supporters of Jokowi used the hashtag #salam2jari (two-finger salute), while #indonesiasatu (one Indonesia) became the sign of support for Prabowo. On election day, voters shared ‘selfies’ showing themselves voting, or their ink-tipped fingers. Social media thus facilitates youth to engage in national discussion on matters related to the elections and political issues in general, not only by providing information but also as a means for them to influence public opinion.

Others went further, using social media to collaborate with other citizens to act politically. This was exemplified by those who participated in monitoring the election results through watchdog sites. For example, c1yanganeh.tumblr.com (the weird C1s c1) facilitated volunteers to collect C1 forms (used for voting tabulation) with irregular data, such as a wrong tally. The tumblr site came up with 900 flagged documents and 100 verified ‘weird’ aberrant’ documents. Similarly, kawalpemilu.org (guard the election) managed to mobilise 700 volunteers to manually count the C1 forms from 47,828 polling stations, releasing the results on its website and Facebook page with an update every 10 minutes. Other sites like kabinetrakyat.org (the people’s cabinet) and kawalkabinet.com (guard the cabinet) facilitated netizens to gather public input on president-elect Jokowi’s cabinet. Overall, social media provides young people with unprecedented means to participate in the political process. But there is a downside.

The paradox of information overload

Prabowo is depicted as the strong general in a computer game developed by Prabowo’s team - Sumarson Social media provides a simple and fast way to access and share independent information, which helps more informed young voters engage in the debate around the elections and other critical issues. However, the abundant free information circulating online also creates a paradox. While social media serves as a potential instrument of political education, it also creates a space where youth can consume information that may not be 100 per cent true.

Prabowo is depicted as the strong general in a computer game developed by Prabowo’s team - Sumarson Social media provides a simple and fast way to access and share independent information, which helps more informed young voters engage in the debate around the elections and other critical issues. However, the abundant free information circulating online also creates a paradox. While social media serves as a potential instrument of political education, it also creates a space where youth can consume information that may not be 100 per cent true.

Online consumers tend to take information for granted without checking its validity and reliability. Digital media users produce, circulate and consume rumours without verifying the original source. In addition, attention spans tend to be short, and deep discussions are rare on social media, where character posts are limited. In this context, social media helped to market a candidate by selling his positive image online, and also to facilitate attacks on a rival by inflaming and sustaining unsubstantiated rumours or outright lies.

One of the consequences of this is reflected in the 2014 presidential elections results, where Jokowi won 53.15 per cent of the vote to Prabowo’s 46.85 per cent. The tight margin shows that almost half of all Indonesians, including the youth, cast their vote for Prabowo. These young people’s political choices seemed to be influenced mostly by his positive online image, rather than his track record of human rights abuses.

The internet indeed provided abundant information on the 2014 presidential elections, paving the way for youth to educate themselves and make an informed political choice. Nevertheless, such free access to unverified information can result in people being misled, as indicated by the many votes still garnered by Prabowo. Another paradox of social media in facilitating youth political engagement is that, despite the increased power of their political activism in the virtual world, these young people are at risk of doing little in shaping real-world politics.

Virtual activism vs. real world politics

Although the political arena has undoubtedly become relatively open in post-authoritarian Indonesia, politics continues to be dominated by elite figures that are entrenched in the networks established during the authoritarian regime. Dominating the political parties, these elite figures look after themselves rather than public interests. That is why youth feel they cannot rely on political parties to pick up their demands, and rather turn to social media as the a new powerful medium to engage in and influence politics. However, youth politics in the virtual world appears to be disconnected from the real. Virtual activism alone seems to be insufficient to challenge the dominance of political elites or oligarchs in the national political landscape.

In the aftermath of the 2014 presidential elections, the young social media activists who helped Jokowi to power appeared to have no say in the political process. There was very little opportunity for them to be part of Jokowi’s high-powered Transition Team which devised his policy programs. They also have little chance of taking part in his administration, where they would be most able to shape crucial policies. Moreover, they lack the necessary political clout to be a powerful pressure group that can influence government policy from the outside.

The limits of virtual activism are demonstrated by the recent controversy surrounding the House of Representatives’ passing of the Regional Election Law that abolishes direct election of regional heads. Many view this as a step backward for democracy, and condemn outgoing president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s (SBY) Democrat Party for walking out during the vote, thus allowing the Red and White Coalition, led by Prabowo’s party, to pass the bill. As a result, #ShameOnYouSBY became a trending topic on Twitter, not only in Indonesia but worldwide, attracting massive public attention to the issue. This public shaming of SBY, damaging his reputation just as he was about to leave office, led him to issue a regulation in lieu of law to repeal the controversial bill. But it is unlikely that SBY’s move will succeed in bringing back direct regional elections. His proposal still needs to be approved by the legislature, where the Red and White Coalition controls the majority of the seats. Social media activists can do little to influence the Red and White Coalition, since they have no power over real-world political processes.

It takes more than virtual activism to promote social change. The strategic resources available online need to be re-entrenched in real-world social infrastructures. In that regard, Indonesian virtual activists may learn from the recent pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. Angry at the Chinese government’s decision to pre-screen candidates for Hong Kong’s first direct elections in 2017, youth leaders Joshua Wang (aged 17) and Alex Chao (aged 24), along with their older counterparts, mobilised a class boycott which was followed by thousands of protesters from other demographics. Seen as the biggest challenge to Beijing since the 1989 Tiananmen movement, these movement’s young leaders managed to mobilise thousands of Hong Kong residents to join their cause, pressuring the government to negotiate. Indeed, They relied on social media to organise invisibly and circulate messages fast. But it was real-world political instruments like mass mobilisation and strong leadership on the streets which made it a successful pro-democracy protest movement.

Diatyka Widya Permata Yasih (diatykawidya@gmail.com) works at LabSosio and Andi Rahman Alamsyah (rahmanega@yahoo.com) works at the Department of Sociology, both at the University of Indonesia.

Other related articles from the II archive:

'Creative Campaigners'. Tom Power, Edition 116: Apr-June 2014

'Cafe Culture'. An Ismanto, Edition 114: Oct-Dec 2013

Inside Indonesia 118: Oct-Dec 2014{jcomments on}