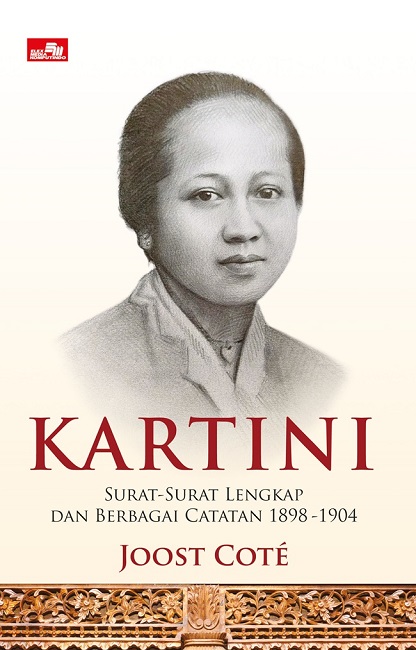

Now published in both English and Indonesian translation, the annotated collection will provide a better understanding of this Indonesian heroine

Ilsa Nelwan

This is an important book that positions Kartini (1879-1904) in a socio-political context in the Netherlands East Indies, the Netherlands and globally. Joost Coté has done impressive work, collecting and translating 141 of Kartini’s letters from various sources, including the original letters published in the Door Duisternis Tot Licht (Out of Darkness to Light). Despite her celebrity status this is the first book containing the complete collection of Kartini’s letters. Now published in both English and Indonesian translation, the annotated collection will provide a better understanding of this Indonesian heroine.

Kartini: The Complete Writings 1898-1904 edited by Joost Coté was first published in 2014. The digital edition followed in 2021, and in 2022 Kompas Gramedia published an Indonesian translation. Joost Coté has researched and published widely on early 20th century colonial modernity in the Netherlands East Indies and has written about Kartini over several decades. He has previously published three translated and annotated collections of correspondence by Kartini and her sisters.

Kartini was born in 1879, the fifth of 11 children, and the second daughter of the Jepara regent Raden Mas Adipati Ario Samingun Sosroningrat. She was the daughter of a secondary wife, Ngasirah, whom he had married before he married an aristocratic first wife as required by his rank. He came from the Condronegoro family, one of the six dynasties in the Pesisir of Java (north coast) who rose to power through association with the VOC, the Dutch East Indies Trading Company, and the later colonial government. The Condronegoro family were educated and progressive people who spoke and wrote in Dutch language.

Kartini left the local elementary school when she was 12 and continued her informal studies with the wife of the local European colonial official, Marie Ovink-Soer. She had access to a well-stocked Dutch language library, supplemented by her father’s subscriptions to leading Dutch language newspapers and literary and cultural journals referred to in her correspondence.

New contributions

In her letters Kartini explained the conditions and traditions in Java and was critical of colonial policy for the Javanese people. Gleaned from her wide reading, Kartini demonstrated her knowledge about what was happening in Europe, what her feelings were towards the Javanese aristocratic tradition in marriage, and how women are neglected.

In the introduction to the 1902 letter collection, Coté explains the connections between Kartini’s efforts to further her studies and her support for the Jepara woodcraft. By this time, she had already established a native girls’ school with an experimental format employing the modern concept of a warm relationship between pupils and teachers and used Javanese language for instruction. This concept was used later by Ki Hadjar Dewantara in the famous ‘Taman Siswa’ schools.

Kartini’s letters represent an important moment in the history of Indonesian nationalism. Written in Dutch language her letters were published in the Netherlands East Indies and in the Netherlands at a time when women authors, even in the West, were still limited in number. She was a figure from a colony who wrote about colonialism in a period in Indonesian history when documentation of nationalism was very scarce.

In his introduction to the second part of the book, Coté provides further context for Kartini’s letters: a description of her childhood, the memory of meeting Rosa, and Kardinah’s marriage. These three letters demonstrate how Kartini used letter writing as a training ground, a preparation for a specific publication in the future. Her letter writing could develop into a literary work or ethnographic report. Kartini’s account of her childhood reveals how she had come to see herself through the lens of interaction with Europe through her reading, writing and publishing. Kartini first received public attention as a 19-year-old when she participated in the National Exhibition of Women’s Work in The Hague and published an article in the leading Dutch scientific journal Bijdragen. She also submitted short stories to the colonial women's journal, Dr Echo, titled ‘A Governor General’s Day’ and ‘A Warship at Anchor’. These articles showed Kartini’s ability as a writer. Not only could she write in Dutch but she could also write with flair.

In the introduction to the fourth part of the book, Coté observes that most of Kartini’s letters were ethnographic in nature. She used her letters to ‘convey to her readers a real description as well as appreciation of Javanese life, society and culture’. Ethnography in the second half of the nineteenth century was on the rise not only because of the European curiosity about ‘primitive society’ but it was also used as a mirror to examine their own culture. While she was clearly influenced by the European ethnographic approach, Kartini could move beyond the role of a mere informant, to present a statement about ‘my people’ and ‘my country’. The collection includes her substantial writings beginning with ‘Het Blauverfen’, an article presented in the National Exhibition of Women’s Work in 1898. The article documented the process of producing the dark blue colouring of the traditional batik cloth, and was an exploration of the traditional world of Central Java. Some years later, in 1914, the Dutch experts on batik, Rouffaer and Juynboll, commended her work not only for being written in excellent Dutch, but important due to her hands-on experience, hence it could create ‘small insight about the finer details of the work’.

The second piece translated in the collection is ‘Marriage among Koja people’. The article was published in Bijdragen in 1899, but written when she was still a girl. It shows Kartini’s keen eye for detail and interest in the rich and diverse heritage of the Pesisir region. In the table of contents for this edition of the journal the piece is noted as being ‘submitted by Raden Mas Adipati Ario Sosro Ningrat, Regent of Jepara’ (Kartini’s father). The protocols for the journal limited women publishing under their own name. Kartini’s successful foray into Dutch scientific discourse is therefore even more remarkable. Not only was this Kartini’s first published writing but it was also the first article published by a Javanese woman in a Dutch scientific journal. The article attracted attention because it was written by an ‘inlander’ (a native) and dealt with a community beginning to attract some attention as a result of the work of Islam scholar Snouck Hurgronje, who may have approved it for publication.

Coté provides further background to the collection by explaining who received Kartini’s letters and her relationships with them. This includes descriptions of Kartini’s relationship with several Europeans who had once been colonial officers in the Dutch East Indies and also with people from the Liberal, Socialist, Feminist, Christian, Philanthropist and humanitarian groups in the Netherlands, with whom she maintained a correspondence. Rosa Manuela Abendanon was the main recipient of the correspondence and may have been responsible for encouraging Kartini to pursue her aspirations and publish her letters. Rosa’s husband, Jacques Henri Abendanon, former director of native education, religion and industry, was the publisher of Kartini’s letters in 1911.

‘The educational memoranda’

Kartini believed that education is everyone’s right and her letter’s make it clear that her efforts were not only intended for the aristocrats. She wrote that education is important for moral improvement, even if not all educated people possess good morality. Her letters and petition mention the right of her people to be a free nation long before her fellow countrymen openly expressed this cause. Such sentiments were the focus of her letters with correspondents in The Netherlands who would later go on to build Budi Utomo.

The important moment for Kartini’s further study was when a member of The Netherlands Parliament, Henri van Kol, visited the colony in April 1902. Van Kol petitioned for a Dutch government fellowship for Kartini and was successful. In the face of opposition from both the colonial bureaucracy and her parents and friends, Kartini accepted Abendanon’s offer of a teacher training position in Batavia instead. After arrangements for her further education were finally confirmed, she was suddenly presented with another obstacle. Her father, her extended family and the colonial officer had negotiated a marriage plan for her. In November 1903, Kartini married Rembang regent Raden Mas Ario Djojo Adiningrat, a Dutch-educated widower with six children and several concubines. All parties agreed that Kartini could continue pursuing her studies, building her school and promoting women’s education.

Kartini’s polygamous marriage was against her own anti-polygamy position, but was common practice in Javanese aristocratic circles. She explicitly mentions this in her letters to Stella Zeehandelar and Rosa Abendanon. Her marriage to a polygamous husband destroyed her dignity, but she agreed to do it out of her love for her father. In the introduction to the 1903 letters Cotè observed that, ‘The shame she admits lay in the fact that her acceptance of a Javanese marriage made her “just like the rest”. What arguably is central here was the sense that the feminist persona she had for so long projected in her correspondence with Rosa and others had now been destroyed.’ Kartini passed away the following year, four days after giving birth to her son.

In 1964 President Sukarno established Kartini as a national hero. Kartini became one of the most well-known figures in the women’s movement in Asia. Every year on 21 April Indonesians mark ‘Hari Kartini’, Kartini Day. For most Indonesians Kartini is known only as a Javanese aristocrat dressed in kebaya, hence this image becomes the Hari Kartini ritual, women dressed in kain and kebaya.

With the publication of the complete collection of Kartini’s letters there is hope for a more meaningful Kartini celebration, including discussion of her writings and thoughts, particularly about women’s education and about equity not only in gender, but also Indonesia’s equity in the world order.

A version of this article was first published in Indonesian language in Kompas.

Ilsa Nelwan (ilsa.nelwan@gmail.com) is a public health doctor and advisor to Yayasan Jaringan Relawan Independent, with a focus on domestic violence prevention and care of for women and children. She is co-author with Noer Fauzi Rahman of Memahami krisis dan kemelut Pandemi COVID-19, published by the Ministry of Education, Research and Technology, 2021.