Lontar Modern Indonesia Series

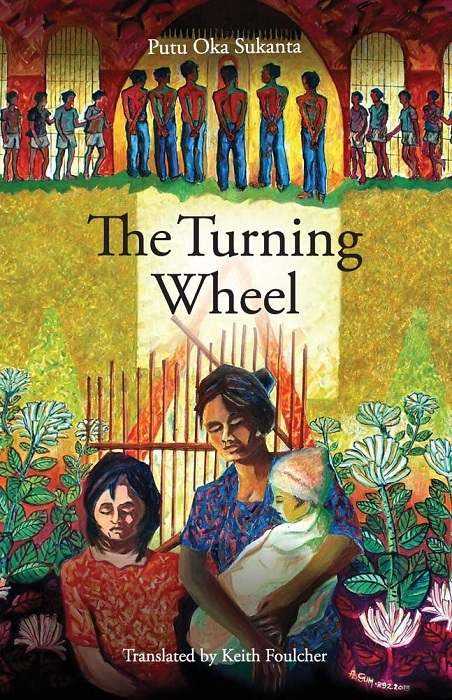

An extract from Putu Oka Sukanta's novel The Turning Wheel. Translated by Keith Foulcher.

Before the events of 30 September 1965, Kirtani leads a busy middle-class life as a kindergarten teacher and mother of two young children, Sayang and Idam. But she is also the wife of a left-wing artist and activist with Communist Party connections. When she receives news of his arrest and imprisonment, her life becomes a struggle for survival

It was now more than three months since Kirtani’s husband had been detained. “He said it would be two months at the most,” she thought. “Why is it taking so long?” She visited the detention center at least once a week to hand over a bag of food and other everyday items, even though she still hadn’t been able to see him. She told herself the important thing was that he was well provided for: soap, toothpaste, cigarettes, and a variety of noodles and other dried food that only needed hot water.

On each of her visits, she always met up with other women in the same situation. Sometimes they sat talking for hours, waiting for the guard to call out their names. Sometimes, too, she would share the cost of a trishaw home with another woman who lived nearby. More often, though, she would pay for the trishaw, to spare her new friend the expense. In comparison to some of the others, Kirtani was still managing to survive financially.

One of the women she saw regularly was Ibu Maruto. They talked more easily in the trishaw on the way home than while they waited their turn outside the detention center, where they were exposed to the heat of the sun or the drenching rain.

“Where did they arrest your husband?” Kirtani asked her one day.

“At home, Bu.”

“Did the children see what happened?”

“No, they were in bed. I’d made a point of asking our neighborhood head to make sure that if they did arrest Maruto they would do it after the children’s bedtime.”

“Amazing that you were able to arrange something like that. Usually soldiers just turn up without warning. They search the house and arrest anyone who happens to be there.”

“They’d tried that several times. But it never worked, because my husband had gone into hiding by then.”

“So how did they get him?”

“It was the children. There’s three of them, and they’re all under school age. Whenever the soldiers and the neighborhood head turned up, they started crying and screaming with fright. The third time they came, they threatened to take me if I didn’t hand him over. They accused me of hiding him. I remember the soldier’s exact words: ‘If I take you into custody, I’ll have to leave the children with your neighborhood head or put them in detention too. Which would you prefer?’ I spent two whole days thinking about it. I was afraid for myself, but even more so for my children. I’ve heard what they do to people in detention. What if they tortured me and the children were forced to watch? I was really frightened.”

Tears kept filling her eyes as she spoke. She wiped them away and went on with her story.

“They were setting fire to so many houses, and public buildings too. The demonstrations were terrifying. I was afraid they’d burn the house down, and we’d have nowhere to go. It’s my parents’ house and it’s all we’ve got. One night three young men turned up after we’d all gone to bed. They had a gun, and they were acting so angry. They said they wanted somewhere to sleep, that it was a PKI house and they had the right to take it. Fortunately the neighborhood head heard what was going on and came and calmed them down. Finally they went away.”

“What happened after that?”

“My husband was working as a bus conductor, so I spent two days looking for him at the bus station in Lapangan Banteng. On the first day I only managed to track down one of his friends, so I asked him to tell Maruto I needed to see him the next day, either at the bus station or at home. I was scared, and the children were suffering too. They had fevers, and they were waking up at night crying and screaming.”

“So what did you do?’

“What else could I do?” she said, her voice shaking.

“How did they catch him?”

“When I heard he was coming, I told the neighborhood head he was going to be at home. I said if they wanted to arrest him, could they please do it after the children’s bedtime.”

“So you handed him over to them?”

“I did. I felt I had no choice. That’s why I keep sending food for him, even though I’m finding it really hard to manage. His bus conductor friend is helping me out, so as long as that continues I’ll keep it up. I haven’t been able to find a job yet. Sometimes one of the neighbors gets me to do some washing or cleaning for her. But the children are giving me a hard time.”

The rhythm of the trishaw’s wheels against the surface of the road felt like the march of time from one day to the next. It lulled them into silence, before the driver sounded his bell and woke them from their reverie. They looked in front of them, gazing into the distance and focusing on a future that was beyond their ability to imagine. It was some time before Kirtani spoke again.

“Where did Maruto work?”

“He was a primary school teacher. And sometimes I helped out at the local kindergarten.”

“Didn’t the school give him any severance pay when he lost his job?”

“The gardener at the school used to bring him an envelope with some money in it every month, on the quiet. They told him to try to find another job, which was the reason he started working as a bus conductor under a false name. I regret it now, because the fact that he left home and worked under a false name gave them an excuse to accuse him of being involved in the disposal of the weapons used to kill the generals. They tortured him to try to make him confess to it.”

Kirtani got out near the market where the dealers in second-hand goods sold their wares. She wanted to know how much she could get for things she still had in the house, like her husband’s typewriter, or the jacket he’d worn when he was part of a delegation that went to see the president during the campaign against American film imports.

“What have you got this time?” asked Pak Danu, a dealer she’d sold goods to on a number of occasions.

“I was wondering if you’d be interested in buying things I might be able to get from other people. Maybe we could work together like that?”

“What sort of things? If the price is right, of course I’d be interested.”

“I was thinking things like radios, fridges, stoves.”

“With things like that, you should leave it to me to do the bargaining. I know what they’re worth. You track them down, and I’ll pay you a commission. What do you say?”

Kirtani said nothing, thinking about Pak Danu’s offer.

“Well? What do you think? I’ll give you a decent commission. Better for you than paying too much for something and finding you lose money on what I can pay you for it.”

From that day on, Kirtani was in business, making contact with old friends who were still prepared to be in touch with her, and seeing if they had things they no longer needed and wanted to sell.

Among her friends were a few well-established film actors who lived in the film industry complex in the old part of the city. She knew some of the younger people in the industry as well, through the classes she’d given them on makeup, costumes, and other aspects of stagecraft. When they heard her husband had been detained, some of them had even visited her with gifts of money, although it had to be done very quietly. She could count on one hand the number of old friends who’d dared to be seen coming in her front gate. Most asked her to meet somewhere else, though certainly not in their homes.

Sometimes she brought Sayang along on her meetings with friends. Schools were still on extended vacation, so mother and daughter were often in each other’s company. They didn’t speak about it, but these meetings gave Sayang an understanding of the work her mother was doing, and the places where she met people. One afternoon, Kirtani took her daughter along to a meeting in a railway station with Makmur, a film worker from her home village in North Sumatra. These days, her extended family lived in Medan, the provincial capital, where Makmur was a family friend.

“Have you told the family in Medan what’s been happening?” he asked her.

“Yes, we’ve talked about it. They’ve asked me to send Idam back to Medan, so my father can look after him and send him to school there. You know it’s only Father and Tiur in the old house now?”

“When are you thinking of sending him? I’m going back next month, so I could take him with me, if you like.”

“I can’t bring myself to do it. The thought of parting with my only son! I’m going to try to hold out here with both of them.”

“I don’t want Idam to go. I’ll have no one to play with,” Sayang whimpered.

“It’s all right, darling. He’s not going anywhere,” Kirtani quickly assured her.

“The situation’s getting worse by the day. Do be careful, won’t you? There are reports of killings everywhere. Buildings being burned down. Demonstrations. I’m thinking of getting out myself, you know.”

Before long, Kirtani and Sayang were heading home. Along the way, their trishaw ran into a noisy crowd of demonstrators yelling slogans like “Hang Chairman Aidit! Gerwani whores! Gerwani whores! Bandrio’s a Chinese puppet!” Sayang stared wide-eyed as the traffic came to a halt. Kirtani’s instincts told her it was time to pay the trishaw driver and move away. She pulled Sayang by the hand into the nearest laneway.

“Where are we going, Ma?”

“Home. This is the quickest way.”

“Who do they want to hang, Ma? Not Daddy, is it, Ma?”

“Shhh. Quick, this way!”

The demonstrators’ chants were still reverberating against the walls of the little girl’s heart. “Hang him! Hang him! Hang him! Gerwani whores! Whores! Hang him! Hang Chairman Aidit! Whores!” Her nerves were carving the words into a set of images that accompanied her every breath. She broke out in a cold sweat, and pressed her stomach in an effort to control the urge to urinate. She struggled to keep up as Kirtani pulled her towards home.

That night, as they lay in bed, Sayang asked her mother about the images that were troubling her.

“Ma, who’s Chairman Aidit?”

“Ask Daddy, when he gets home.”

“Why do they want to hang him?”

“Ask Daddy. He’ll explain it.”

“What does ‘whores’ mean, Ma?”

“I’m tired, darling. Let’s just go to sleep now.”