Dahlia Gratia Setiyawan

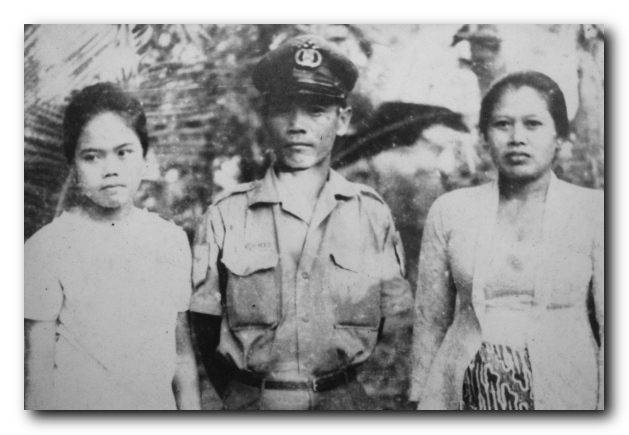

Sri and her parents, her father in his police officer's uniform |

In the days immediately after 1 October 1965, army units and civilians in Surabaya – a known PKI stronghold – began to move against the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). Arrests of suspected members of the party and affiliated organisations began as early as 2 October but the campaign gained momentum when hundreds of people attended an anti-communist rally on 16 October near the towering obelisk built to commemorate the heroism of the people of Surabaya in the revolution.

Two days later, a military decree was issued demanding that all state employees with ties to the PKI or PKI affiliates report to local authorities and on 22 October the PKI and its affiliate organisations were banned in the city. As the month drew to a close, Surabaya’s PKI-backed mayor, Moerachman, was imprisoned and eventually disappeared after likely having been murdered by his captors. Lieutenant Colonel Sukotjo from East Java’s Brawijaya Division quickly took his place.

Sukotjo immediately began a wide-reaching and violent campaign to cleanse the city of communists. One of the neighbourhoods targeted by anti-PKI raiding parties at this time was Simo Jawar in the sub-district of Tandes on the outskirts of Surabaya. The story that follows of the anti-communist militia raid in Tandes towards the end of 1965 is the account of Hadi and Sri, two teenagers who survived that night of terror, who later married and still live nearby.

Marked for death

On the night of the raid, anti-PKI militias from other districts gathered in Tandes to meet a local anti-communist coalition comprised of members of Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and the Indonesian National Party (PNI). According to Hadi, the attackers knew who to target when they headed out to cleanse the district of communists because their co-conspirators provided them with lists of names and addresses.

The raid unfolded over the neighbourhoods of Tandes. It began in Simo Jawar before moving to Donowati, Sukomanunggal, Tanjung Sari, and beyond. It was clear from the precision of the attacks as they fanned out through the sub-district that the raiders planned not to apprehend but to kill. Hadi, who was fifteen years old at the time, and the youngest of eleven siblings, recalls, 'There were trucks full of people, regular people, not army, but I don’t know if they were backed up by the military. They were carrying sickles and machetes. They stopped at the front of Simo Jawar cemetery. There were several trucks. Those people got out, ran through the cemetery and entered through the road that ran along the back of people’s homes.'

It was obvious to Hadi and the other villagers upon hearing the story from eyewitnesses the following day that outsiders who attacked the neighbourhood belonged to the Indonesian Nationalist Party (PNI) and NU’s youth organisation, Ansor. The intruders were all dressed in black with coloured strips of cloth tied around their necks or arms, the PNI’s red and Ansor’s green.

It was clear from the precision of the attacks as they fanned out through the sub-district that the raiders planned not to apprehend but to kill

As those planning the raid expected, on their approach the villagers ran to the north towards the paddy fields behind their houses, where they thought they would be safe. The attackers left their footprints in the mud behind the houses, along with some random items of clothing and even shoes, discarded in the fray. The next morning, the body of a youth suspected to be a PKI member was found hacked apart in the paddy fields of Sukomanunggal. In Donowati the mutilated body of a pedicab driver called Sapon was located in a plot of bananas where he had tried to hide.

Calling for help

Sri, the girl who was later to become Hadi’s wife, came from a family with no PKI connections who lived on the opposite side of Jalan Raya Simo Jawar, the single road that passed through the neighbourhood.

When the attack began, Sri’s father, a police officer, ordered his family to stay inside. At around 11 pm, another police officer began shooting at the house, and yelling at her father, accusing him of supporting the raid. Quickly changing into his uniform, he grabbed his gun and, with his weapon cocked and ready to fire, went to open the front door. Terrified that her father would be killed by his colleague and the rest of the family murdered in their home, Sri and her mother and brother hid under the bed, crying and clutching onto each other, and praying for their survival.

Having convinced his friend that he wasn’t involved in the violence, Sri’s father agreed to accompany him to the local police station. But as they passed through the chaotic Tandes streets, he decided instead to run through the marshes to the regional police headquarters in Kembang Kuning in order to get help from the mobile brigade special police (BRIMOB). Several hours later, from her hiding place under the bed, Sri heard a truck approach and then stop in front of her house. A group of BRIMOB officers descended looking for her father who had contacted them by telephone from the Kembang Kuning office. After being informed that he was not at home, they departed through the neighbourhoods in Tandes, firing warning shots as they went.

The aftermath

The fear that their night of terror would be repeated caused residents to flee the area. Upon their return around a week later, a shroud of silence fell over Tandes. No-one said anything even when one of the local NU leaders who had helped compile the hit-lists provided to the attackers transferred the property of his former landlord – who had disappeared – into his own name.

Eventually, though, a tentative rebuilding began in the village. Sri’s father continued in his position with the Tandes police. After some years even survivors who had been held without charge or trial, like the tax collector Legiman and his brother Sali, made their way home, albeit to live forever branded as former political prisoners.

Hadi and his family waited anxiously for the return of his brother Banawi, a mechanic who had worked for the state-owned shipbuilding company in the Surabaya port of Tanjung Perak. Banawi had been an active member of the PKI youth wing, Pemuda Rakyat. Due to his affiliation with this organisation, he had been detained well before the raid, along with others including Legiman and Sali, in an abandoned building in the Mlaten region of Kedurus, around eight kilometres from Simo Jawar.

Despite anxious efforts to find him – even risking paying a distant relative who was a sergeant in the Tandes Military District Command to make enquiries – Banawi was never found. According to the brothers Legiman and Sali, he had been reportedly shot in the leg by guards while attempting to escape from prison. While Hadi suspects that his brother might have been one of the prisoners taken away by local militias and shot, he will never know for sure.

Today, the terror of that night is a topic that is rarely, if ever, openly discussed. As a result, the younger generation and newcomers to the region have no knowledge of the area’s tragic history. Many of those who survived the raid or lost family members to the PKI purge remain fearful to speak of what they experienced or simply see no purpose in dredging up the past. Hadi and Sri are also fearful of repercussions. But they felt they must speak out so that memories of the victims and of the violence in Tandes will endure in their family and among their community, and so that the events of that night and of the months before and after it may be acknowledged by the wider world.

Dahlia Gratia Setiyawan (dsetiyawan@ucla.edu) is a PhD Candidate at the University of California, Los Angeles.