Brad Simpson

Confidential documents reveal the secrets of 1965Brad Simpson |

Recalling the mass killings in Indonesia following the 30 September 1965 movement, Howard Federspiel, the US State Department's intelligence staffer for Indonesia, observed that 'No one cared as long as they were Communists, that they were being butchered.' Indeed, it is hard to find any western governments that expressed concern about what the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) called one of the great mass murders of modern history. Far from it. Western governments, led by the United States, actively sought to create conditions that would lead to a violent clash between the army and the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and, once the mass killings began, offered quiet but enthusiastic support to the Indonesian army. The killings of 1965 and 1966 were, in other words, international events of global significance, as the governments that supported the army in carrying out the killings recognised.

Encouraging a violent clash

For nearly a decade preceding the events of 30 September 1965 the US feared the growing radicalism and anti-westernism of President Sukarno and the increasing political power of the PKI. These twin fears led the Eisenhower Administration into a massive and disastrous covert operation in support of the regional rebellions of 1957-1958, events that led directly to Sukarno's abandonment of parliamentary democracy and the implementation of the authoritarian system known as Guided Democracy. Eisenhower's successors, John F Kennedy and Lyndon B Johnson, each used programs of economic, technical and military assistance to encourage a greater role for the Indonesian armed forces in Indonesia's economic and political life as a means of blunting or reversing the influence of the PKI.

In August 1964, as relations between the US and Indonesia deteriorated rapidly, in part due to Sukarno's confrontation with Britain over the formation of Malaysia, the US went further, adopting a covert strategy aimed at sparking a violent conflict between the military and the PKI. In doing so the US joined Britain, which had adopted a covert warfare approach in 1963, attempting to frustrate Indonesia's campaign to block the formation of Malaysia and, if possible, provoke 'a prolonged struggle for power leading to civil war or anarchy' in Indonesia itself. Officials in both countries agreed that the army was reluctant to crush the PKI unless first provoked, so the crucial question was: how do we make such a clash inevitable? Edward Peck, Assistant Secretary of State in the Foreign Office suggested 'there might be much to be said for encouraging a premature PKI coup during Sukarno's lifetime' - provided the coup failed.

Speaking out for the army

US and British concerns became moot once the 30 September Movement, known in Indonesia as G30S, acted. Though they reacted to the events of 1 October with surprise and confusion, western officials, including US Assistant Secretary of State, George Ball, immediately recognised that 'If the Army does move they have [the] strength to wipe up [the] earth with [the] PKI and if they don't they may not have another chance.' The CIA warned that the army might only 'settle for action against those directly involved in the murder of the generals and permit Sukarno to get much of his power back'. Since no Western intelligence agencies argued that PKI involvement in G30S extended to the rank and file, one can only conclude that their greatest fear was that the army might refrain from mass violence against the party's unarmed members and supporters.

The US and Britain, joined by Australia, offered their early support for the army by both creating and distributing propaganda, seeking to demonise the PKI and attempting to tie G30S to China. By mid-October, US Secretary of State Dean Rusk cabled Jakarta, noting that the time had come 'to give some indication to [the] military of our attitudes toward recent and current developments'. He writes further: 'If [the] army's willingness to follow through against the PKI is in any way contingent upon or subject to influence by [the] US, we do not wish [to] miss [the] opportunity for US action.' General Nasution provided an opportunity when his aide approached the US Ambassador to Indonesia, Marshall Green, to request portable communications equipment for use by the Army High Command.

As the first reports of mass killings began arriving at the embassy in Jakarta, US officials began considering further covert assistance to the army in the form of food, raw materials, access to credit and weapons for use against the PKI. At the end of October, White House officials began planning to provide covert aid to the Indonesian military, which, according to the US embassy, was 'moving relentlessly to exterminate the PKI'. This marked the beginning of a limited but politically significant stream of aid, which included the provision of small arms and cash to army officers.

In the following weeks western embassies in Jakarta fed on a steady diet of gruesome reports about the massacres. At the end of October, reports of mass attacks against PKI supporters in East, Central and West Java reached the US embassy. A military advisor just returned from Bandung reported that villagers were handing over PKI members and those belonging to PKI affiliated organisations to the army for arrest or execution. On 4 November the embassy cabled the US State Department to say that the Army Paracommando Regiment (RPKAD) forces in Central Java under Sarwo Edhie's command were training and arming Muslim youth to attack the PKI. While army leaders arrested higher level PKI leaders for interrogation, the cable noted that 'smaller fry' were 'being systematically arrested and jailed or executed'. A few days later the US consulate in Medan reported 'wholesale killings' of alleged PKI supporters in North Sumatra and Aceh and the 'specific message' from the army that it was seeking to 'finish off' the PKI.

From propaganda to active assistance

In order to facilitate its covert assistance to the Indonesian army, the US worked with General Sukendro, who had studied at the University of Pittsburgh and was one of the CIA's highest level military contacts. The US also had a designated liaison in Bangkok, with whom it discussed the army's requests for communications equipment, small arms and other supplies totalling more than a million US dollars. Sukendro told his US counterparts that the army's greatest need was for portable voice radios for the general staff in Jakarta; an army voice circuit linking Jakarta with military commands in Sumatra, Java and Sulawesi; and tactical communications equipment for army units operating in Central Java. US officials in Jakarta recommended approval of Sukendro's request as 'critical' in the army's struggle against Sukarno and the PKI.

On 13 November, police information chief, Colonel Budi Juwono, reported that 'from 50-100 PKI members are being killed every night in east and central Java by civilian anti-Communist groups with [the] blessing of [the] Army'. Three days later 'bloodthirsty' Pemuda Pantjasila members informed the consulate in Medan that the organisation 'intends to kill every PKI member they can get their hands on'. Other sources told the consulate that 'much indiscriminate killing is taking place'. Consular officials concluded that, even accounting for exaggerations, a 'real reign of terror' was underway. The CIA reported late in November that former PKI members in Central Java were being 'shot on sight' by the army, while western missionaries in East Java told the US Consulate in Surabaya that 15,000 communists had reportedly been killed in the East Javanese city of Tulungagung alone.

Consular officials concluded that, even accounting for exaggerations, a 'real reign of terror' was underway

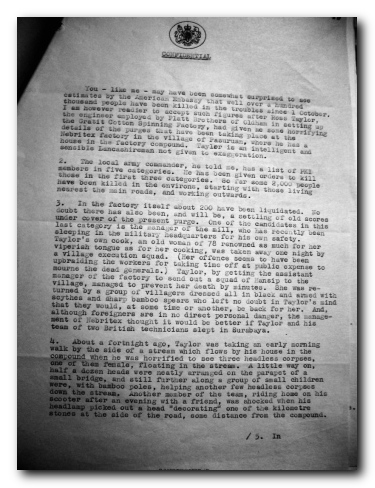

British reports largely paralleled those of their American counterparts. In the village of Pasuruan in East Java, a British engineer named Ross Taylor working at Gratit Cotton Spinning Factory described the massacres of workers at the Nebritex textile factory to consular officials. Using lists of known or suspected members of the PKI and the PKI-linked trade union SOBSI, the local army commander placed victims in one of five categories, killing those in the first three and arresting the rest. Ross estimated that 2000 people had been killed in the vicinity of the factory (and at least 200 from the factory itself) since late November, with army units working from the main roads and radiating outwards.

At the height of the massacres the Johnson Administration continued to extend covert assistance directly to the forces carrying out the killings, apparently including small arms delivered to the army through the CIA station in Bangkok. In early December, the State Department approved a covert payment of fifty million rupiah to finance the activities of the Action Front to Crush the 30 September Movement (KAP-Gestapu). Marshall Green noted approvingly that Kap-Gestapu's activities 'have been an important factor in the army's program', especially in Central Java where it was leading the attack on the PKI. US officials have confirmed that the embassy also turned over lists identifying thousands of PKI leaders and cadres to Indonesian army intermediaries, who used them to track down PKI members for arrest and execution.

US officials, like their counterparts in the army, viewed their campaign to eliminate the PKI leadership and destroy its infrastructure in strategic terms, as 'a power struggle, not an ideological struggle' with a rival power centre. The British Consul in Medan framed the contest between the army and the PKI in Sumatra, where both groups were concerned with the control of local ports, rubber estates and tin mines, as one for foreign exchange reserves and access to resources. Not surprisingly, the rubber estates in northern Sumatra were the scene of some of the bloodiest attacks against PKI supporters, with, according to the British consulate in Medan, the army 'arresting, converting or otherwise disposing of some 3,000 PKI members a week'.

An ominous silence

The western response to the mass killings in Indonesia was enthusiastic - and instructive. Washington continued its assistance long after it was clear that mass killings were taking place and in the expectation that US aid would contribute to this end. Not a single official ever spoke against the slaughter. 'Our policy was silence', Deputy US National Security Advisor Walt Rostow later wrote in his correspondence with President Johnson, a good thing, he said, 'in light of the wholesale killings that have accompanied the transition' from Sukarno to Suharto. The US was not alone. Thailand offered rice to the Indonesian army on the condition that it destroy both the PKI and Sukarno. Even the Soviets continued to ship weapons throughout the period in an effort to maintain relations with the military and further undermine Chinese influence. New Zealand embassy officials in Jakarta reported in December 1965 that their Soviet counterparts were 'letting it be known to the Generals that if it comes down to a choice between the PKI or no PKI, the USSR would prefer the latter'.

Indonesia's international supporters could have pressured it to limit the scope and scale of the violence - had they considered it in their interests to do so. But the US and its allies viewed the wholesale annihilation of the PKI and its civilian backers as an indispensable prerequisite to Indonesia's reintegration into the regional political economy, the ascendance of a modernising military regime and the crippling or overthrow of Sukarno. Indeed, Washington did everything in its power to encourage and facilitate the army-led massacre of alleged PKI members and US officials worried only that the killing of the party's unarmed supporters might not go far enough, permitting Sukarno to return to power and frustrate the Administration's emerging plans for a post-Sukarno Indonesia. This was, in short, efficacious terror, an essential building block of the quasi neo-liberal policies the West would attempt to impose on Indonesia in the years to come.

Brad Simpson (bsimpson@princeton.edu) is Assistant Professor of History and International Affairs at Princeton University and the author of Economists with Guns: Authoritarian Development and U.S. - Indonesian Relations, 1960-1968 (Stanford, 2008).

Brad is also director of the Indonesia and East Timor Documentation Project at the National Security Archive (http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/indonesia/index.html), which is working to declassify US documents on Indonesia from the Suharto era to the present.