Regional autonomy and spatial planning in Bandung benefits the elite

Gustaaf Reerink

Indonesia’s post-Suharto reforms and particularly the 1999 regional autonomy laws were supposed to contribute to political decentralisation and democratisation at the regional level. However, spatial planning processes illustrate that there is a continued lack of transparency and public participation in decision making at the regional level.

Indeed, the logic of administrative decentralisation and the new fiscal relationship between Jakarta and the regions invites regional governments to consider spatial planning merely as an instrument to stimulate economic development, without taking the interests of ordinary citizens into account. Practices of corruption, collusion, and nepotism, and the increasing role of hoodlums (preman) in local politics, mean that spatial planning remains as closed to the public as it was during the Suharto era. Even when the resulting spatial plan violates higher legislation, which is legal grounds for the higher levels of administration to annul the plan, the local governments can get away with it because of weak supervision by the provincial government and the lenient attitude of the central government. Nowhere is this clearer than in Bandung, the sprawling city of 2.5 million people that is the capital of West Java province.

Raising revenues

The regional autonomy laws of 1999 led to a reorientation of Bandung’s development policy aimed at gaining new revenues. Decentralisation provided the city with plenty of new powers, but it needed funds to be able to finance the exercise of these powers. In response, in 2000 the municipal government introduced the ‘Bandung: City of Services’ concept. As the city is not well-endowed with natural resources and has relatively limited industrial activity, government officials saw the service industry as the only sector that could generate economic growth and so provide the additional revenues needed.

Spatial planning remains as closed to the public as it was during the Suharto era

One method of raising revenues was provided in 1999 when authority to grant ‘site permits’ (izin lokasi) – permits that allow businesses to acquire land for development – was devolved from the provincial level down to the district/municipal level. Granting permits generates local revenues in at least three ways. First, businesses pay fees directly to the municipal government for the site permits. Second, commercial land development increases the value of land, which in turn yields higher land taxes for the government. Finally, the new businesses operating where site permits have been granted produce extra local revenues through advertising, parking, hotel and restaurant taxes (especially because the Bandung municipal government has also revised existing by-laws regarding such taxes and introduced new ones).

The new development policy proved successful. According to Bandung’s regional budget, between 1997 and 2006 various revenues increased spectacularly, some by as much as 900 per cent.

Post-New Order political reforms also meant that politicians required additional revenues to buy political support, for instance to ensure a mayor’s re-election or to get draft legislation passed. This support could be obtained through generous budgeting. Between 1997 and 2006, the funding for Bandung’s municipal council increased by almost 700 per cent. But political support is also financed by extra-budgetary revenues, which again partly derive from the newly acquired authority to grant site permits. In September 2003, this logic was demonstrated when the city council (DPRD) elected Dada Rosada from the Golkar party as the new mayor, rather than re-electing the incumbent who had presided over the increases in funds to the council. Several well-informed sources allege that the new mayor paid over Rp.100 million (A$14,000) to each member of the council who voted for him. Funding was provided by businesspeople, who expected to be compensated later in the form of site permits.

Developing the conservation zone

Laws stipulate that site permits should be granted in accordance with municipal spatial plans. In the early 2000s, Bandung was due for a new ‘General Spatial Plan’, so the new municipal government presented the council with a draft. This draft cleared the way for commercial land development, including the replacement of slums with tenement buildings, so that the rest of the land could be used for commercial purposes. Traditional markets could also be relocated for the same reason.

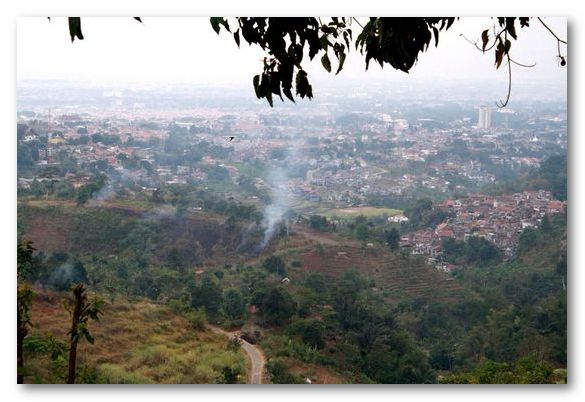

The plan even allowed for real estate development in the scenic hills of the rural area Punclut. Punclut is a part of the environmentally sensitive Northern Bandung Conservation Area which serves as a water catchment zone and plays a vital role in protecting the southern part of the city against flooding.

Post-New Order legal reforms resulted in clear provisions for participation and transparency in spatial planning, and NGOs attempted to play an active role in the process. However, while there was some participation, the final draft of the Bandung spatial plan showed that input had been largely ignored. The drafting process was also non-transparent, and the municipal council accepted the draft presented by the government without any substantive discussion. Notably, accusations emerged that several members of the council had accepted bribes from a company that wanted to develop real estate in Punclut, but police never seriously investigated these accusations.

The plan even allowed for development in the water catchment zone

The development of real estate in Punclut was in violation of higher legislation, including the spatial plan of West Java province. However, the 1999 regional autonomy laws stipulated that the implementation of the municipal spatial plan no longer required a recommendation from the governor, so the governor could do little but send non-binding letters to the mayor and voice his objections through the media. The National Development Planning Agency also criticised the development of Punclut, but the Department of Home Affairs did not use its authority to annul the plan, and it was enacted in 2004.

Revisions and protests

|

|

Punclut threatened by encroaching development / Blair Palmer |

Ignoring the objections from provincial and central governments, the mayor issued permits for real estate development in Punclut. Construction of an upper class housing development and an international school had actually already commenced, and they continued. Some of these permits even contradicted the newly enacted municipal spatial plan. This resulted not in the cancellation of the permits, but in proposed revisions to the spatial plan, in 2005. The new draft plan allowed for the construction of a road in Punclut, as well as further opportunities to evict slum dwellers and to relocate traditional markets.

This time there was even less room for participation and transparency in the drafting process. Although the composition of the municipal council had changed significantly due to the 2004 legislative elections, and several members had initially been critical about the plan to develop Punclut, the council again accepted the plan without much discussion. The governor was critical of the plan, but it was enacted anyway in March 2006. The Department of Home Affairs again failed to annul the plan.

Hoodlums responded by organising counter-protests and intimidation campaigns

Environmental NGOs sent letters to high officials, organised street protests, and issued a ‘Red Report’ in which they criticised Mayor Dada Rosada for his environmental policy. These activities required courage. Hoodlums responded by organising counter-protests and intimidation campaigns. It is said that they were mobilised by certain members of the municipal council affiliated with Bandung’s most powerful hoodlum group, the Siliwangi Youth Force (Angkatan Muda Siliwangi). Such groups receive funds from Bandung’s regional budget, as well as other means of support, particularly since the election of Mayor Dada Rosada in 2003.

The price of power

There is little chance that there will be more room for public participation and transparency in spatial planning in Bandung in the near future. On 10 August 2008 the first direct mayoral elections in the city were held, which resulted in the re-election of the incumbent, Dada Rosada. Informal reports indicate that the incumbent’s candidacy cost him much more during these direct elections than in 2003, perhaps several million dollars, including payments to the six political parties that supported his candidacy as well as the costs of his election campaign. To cover these costs, it is likely that the mayor will issue new permits. This may even result in a new proposal to revise Bandung´s spatial plan.

Sobering experiences like this illustrate that Indonesia’s legal reforms have not yet created a balance of power between the three branches of government, between Jakarta and the regions, and between state and society. These imbalances require further reforms to restrict corrupt practices and preman-style politics, and to prevent a one-sided focus on economic development at the expense of environmental protection and social justice. ii

Gustaaf Reerink (goreerink@yahoo.com) is a PhD candidate at the Van Vollenhoven Institute for Law, Governance, and Development, Faculty of Law, Leiden University. He will defend his dissertation, entitled ‘Land Tenure Security for Indonesia's Urban Poor, a Socio-Legal Study in the Kampongs of Post-New Order Bandung’, at the end of 2009.