Peter Walters, Imam Ardhianto, Sonia Roitman & Rusli Cahyadi

Work has started on Indonesia’s new capital city, Nusantara (Ibu Kota Nusantara – IKN), in East Kalimantan on the island of Borneo. This mega infrastructure project is the most extensive and most expensive ever undertaken in Indonesia. The city is a legacy project for President Joko Widodo (Jokowi). The move is due to the increasing precarity of Jakarta, one of the world's most congested and rapidly growing conurbations. Jokowi has claimed that traffic in Jakarta costs A$4.6 billion in economic losses per year. The effects of climate change, inadequate drainage and population pressure mean the low-lying city is slowly sinking into the sea. However, Jokowi has been at pains to remind Indonesians that the idea was not his. Sukarno already suggested relocating the capital away from Java for symbolic cultural and political reasons. The name Nusantara reflects this national vision (Wawasan Nusantara) to incorporate the whole archipelago and to distance governance away from Java and the nation’s Java-centric past.

In an ambitious program of work, the official opening of Stage One of the Project is planned for national Independence Day on 17 August 2024. It will include the central institutions of national government such as the presidential palace, houses of parliament, and armed forces headquarters. According to the plan, all government offices and public servants will have moved to the new city by 2034. Jokowi, in a visit to the site in February 2023, supervised the beginning of construction of 34 ministerial residences to be completed by June 2024.

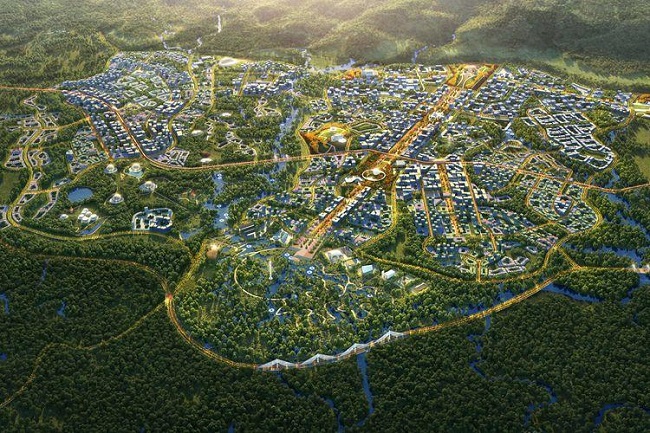

253,000 hectares are set aside for the capital special area straddling two regencies in East Kalimantan, Kutai Kartanegara and Penajam Paser Utara, an hour and a half drive north of Balikpapan. The site includes industrial forestry concessions, indigenous customary lands and transmigrant agricultural communities. The design of the new city is ambitious - a showcase for contemporary urban planning in the Southeast Asian region. The city promises to be high-tech, smart, and ecologically sustainable, comprising 70 percent green space and 30 percent built form. Energy will be 100 percent renewable; public transport will be by autonomous electric vehicles; and 10 percent of the city's land area will be devoted to growing food with 100 percent recycled wastewater. The project budget will comprise less than 20 percent public investment, with most of the development costs covered by the private investment. To that end Jokowi has visited Singapore on several occasions to attract investors. However, the private sector remains reluctant to invest without more certainty that the project will proceed. Adding to the uncertainty are claims that the project is being designed to benefit wealthy individuals with land interests in the area.

Equity

The ambition and truncated timetable for the project pose some critical questions for equity and feasibility. We visited the site of Ibu Kota Nusantara in late 2022 and early 2023 as part of a research collaboration between researchers from the University of Indonesia, the Indonesian National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) and the University of Queensland. We met local landowners, community leaders, government officials and small property developers where they lived and worked. We asked them at length how they saw the development impacting the site. Our research is on the social and economic impacts on the local population, who will be profoundly affected by the construction of the city and by the influx of new residents. Challenges include increased pressure on existing services and infrastructure, especially water supply, already a key challenge for the adjoining city of Balikpapan. We will focus on growing inequities in land ownership and acquisition.

By far the most pressing issue is land rights and tenure. The site zoned for the new city is currently home to around 20,000 people occupying about 40 percent of the land area, incorporating a complex web of tenure and ownership. In addition to indigenous groups, migrants have been moving to this area since the commencement of logging of native forests in this area 50 years ago. There is a long history of marginalisation and land-grabbing in this area. Industrial forestry operations and pulp concessions by companies such as ITCI Hutani Manunggal commenced in the 1970s.

To fast-track planning and development, IKN has been granted the status of a National Strategic Project. This means little will now stand in its way. Local and provincial laws and regulations that governed the area now have very limited power. Acknowledgement of customary laws on land (Masyarakat Hukum Adat) is now less certain as the district level government needs to consider new political and regulatory constraints. While there is provision in the National Regulations for IKN to recognise traditional land ownership, there is uncertainty about how this will be implemented in the event of a traditional claim on land within the IKN zone. Resistance and representation for traditional owners will be more difficult in national regulatory environments where networks and social capital may not be as strong as they are locally. However, there are some grounds for optimism, with the appointment of mid-level officials to the IKN authority with a strong NGO background. These might be expected to prioritise local environmental and community concerns.

For NGOs supporting local communities, the pace with which this National Strategic Project was implemented has given rise to fears that central planning authorities have not adequately identified the existing local institutions that manage and recognise land-tenure for traditional owners and other marginalised groups. For example, The Indonesia Alliance of Indigenous Peoples (Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara and the Customary Areas Registration Body (Badan Registrasi Wilayah Adat) invited eight customary community representatives for a workshop on participatory community mapping of customary areas in November 2022. Indigenous groups included Paser Balek, Tonyooi, Semoi, Mentawir, Pemaluan, Maridan, Basap and Kenyah Lepo Jalan. These groups are likely to be evicted from their cultural lands or indirectly impacted by the infrastructural development related to the IKN. The NGOs could do little to give these groups confidence that their interests would be protected. Claims to this land are based on origin narratives with a long and complicated history. The national-level Ministry of Environment and Forestry potentially allows for formal recognition of customary forest areas. But claims require legislative support from district level government, and this process will face strong political and regulatory obstacles. Recognition requires legal acknowledgement by decree from the district head (camat), but the National Strategic Project mandate can now bypass this. This makes rights difficult to establish. Competing claims to the same land by different indigenous groups add further complications. Anyone outside those groups will find it challenging to determine which claims are valid, and the groups themselves are yet to be consulted.

The second claim to land is by transmigrants, mainly from Java and Sulawesi. They moved here under the massive transmigration program during the New Order years from 1979 onwards, as part of five-year development plans to ease population pressure. Transmigrants were awarded land, often at the expense of traditional owners. They have now been in place for 40-50 years. Their communities and small-holder agricultural enterprises are well established. These groups have a more straightforward formal legal claim to the land they occupy than the hereditary claims of indigenous groups. Finally, there are transmigrant and indigenous communities who occupy land in concessions owned by industrial plantation operators and wealthy Jakarta-based corporations. These concession holders allow parts of their land to be occupied by these groups and communities as they provide necessary labour to the forestry and palm oil concessions.

Volatile

Where they exist, negotiations for land compensation have been made more complex and potentially volatile by spectacular increases in land values created by speculation following the announcement of the new capital site in 2019. Land valued at Rp20-50 million per hectare (A$2,000-5,000) before the announcement is now valued at Rp1 billion (A$100,000) per hectare. In response to these speculative increases in land values, the Indonesian Government at regency, provincial and national levels announced a ‘land freeze’ progressively from 2019. This has put an end to legal local speculation, as small developers can no longer apply for bank finance for this land or make legal land transactions. However, it has not prevented 'under the table' deals by what the popular press has dubbed the ‘land mafia’, referring to large Jakarta-based corporations. They buy land outside the formal regulatory and banking systems and simply wait for the land freeze to end before exchanging legal title. Locals fear that the land freeze will only benefit these large Jakarta-based developers, and punish small, locally-based ones. It will also prevent adequate compensation and relocation efforts for existing residents. Permits to develop land granted to local developers are already being overturned in the interests of national level developers. A local developer told us that small local developers felt like they were ‘house cats amongst a group of lions’.

Even for those who can afford to wait out the land freeze - among them farmers and other small landholders - are ambivalent about expected windfall profits. They fear compensation payments will not cover new land purchases and business re-establishment costs for sites anywhere close to where they are operating now. The head of one village in the current IKN development zone told us that any compensation they had been promised would not reflect the speculative increase in land values that had taken place since then. Several village heads spoke of the unhealthy ‘rumour mill’ about IKN that had developed in the absence of genuine consultation from the national government.

Meanwhile, those on the fringes of the development zone, who were confident they would remain in their villages, were optimistic about the economic development and employment opportunities the IKN would bring. IKN would put them ‘on the map’, bringing paved roads, new retail opportunities, services and infrastructure such as healthcare. However, they were already seeing the negative effects of large numbers of imported construction labourers on the ‘moral fabric’ of the local communities, as they witnessed the arrival of alcohol, drugs and sex workers.

Beyond all these issues, locals tended to think construction would go ahead despite any objections they might have. Despite (or perhaps because of) the enormous scale of the project, there has been minimal consultation or information from planning authorities with local stakeholders. Local informants agreed that the establishment of the new capital was hostage to politics. At the same time, they recognised that the politics themselves are uncertain. While many welcomed the improved infrastructure and economic activity that new migrants to the city would bring, there was caution about whether the project would survive Jokowi's tenure. Since the fall of Suharto in 1998, Indonesian presidents have been limited to two terms. Jokowi will step down at the end of 2024 following the February election. His ambition is to officiate at the inauguration of the initial zone on 17 August 2024. Few of those we spoke to disagreed that Nusantara can relieve pressure on a climate-threatened, overcrowded, gridlocked Jakarta. But everyone acknowledged the project was political – a 'Presidential legacy'. If one of the presidential candidates in February 2024 campaigned hard to oppose it, it could be derailed.

Peter Walters (p.walters@uq.edu.au) teaches sociology at the University of Queensland. Imam Ardhianto is an anthropologist at the University of Indonesia. Sonia Roitman is an urban planner at the University of Queensland. Rusli Cahyadi is a researcher at BRIN.