Joost Coté

In their introduction to Merdeka the authors, Henk Schulte Nordholt and Harry Poeze, challenge their potential readers with a rhetorical question: ‘Why should two white Dutch researchers write a book about a revolution that is not theirs?’ Their response is that they intend to provide a new interpretation of the last years of Indonesians’ struggle for independence, which sets aside both the popular narrative that has sustained Indonesia’s postcolonial national identity and the dominant international interpretation. In particular, they wish to distance their analysis from explanatory devices based on more extreme interpretations of it as being a revolusi, and from Benedict Anderson’s influential concept of the ‘imagined political community’, which they describe as ‘romantic’.

In the context of the flurry of publications emanating from the Dutch government-sponsored investigation into Dutch military operations during the 1945 – 1949 Indonesian War of Independence (summarised in Gert Oostindie, Beyond the Pale, 2022), the authors makes clear they are not concerned to further document Dutch military atrocities and directs readers to Remy Limpach’s 2016 book De Brandende kampongs van Generaal Spoor (General Spoor’s Burning Kampongs) - another book awaiting an English translation. Schulte Nordholt and Poeze’s argument, in short, is that the modern Indonesian state was the outcome of a long political struggle between different Indonesian stakeholders, advocating different conceptions of a future independent Indonesian nation.

Merdeka provides a carefully delineated chronology of the fast-moving history that took place in Indonesia between 1945 – 1949. Unlike the publications emanating from the Dutch government-sponsored investigation into Dutch military operations during the 1945 – 1949 Indonesian War of Independence, the authors make clear their intention is to appreciate the complexity of the Indonesian Revolution, rather than focus on the colonisers only.

Presented in thirteen chapters across 400 tightly packed pages the study is based on the authors’ systematic analysis of a broad range of many hitherto lesser known – or ignored - archives. It is written in a way that ensures that, as well as being an important historical study, the book provides a ‘gripping read’ that urgently awaits an English translation. It is concerned to highlight the diversity of political agendas and ideologies pursued by various nationalist groups and political parties. It identifies the political machinations they were engaged in, the constituencies they sought to influence, and how each contributed to shaping Indonesia’s pathway to independence. It is these diverse historical conceptions of a national identity that have continued to disturb the post-colonial nation.

Intertwined throughout this chronology of the political formation of the Indonesian state, is reference to the continuing self-interested intervention of the former colonial power and, in the context of the emerging Cold War more broadly, the significance of the intervention of the US in its pursuit of post-war global hegemony.

Just as in a brief review such as this it is not possible to enter into all the fascinating detail that the authors uncover, the whole story of the 1945 – 1949 period could not be accommodated in a single volume. The individual chapters, therefore, function to isolate and analyse the key moments and movements shaping the political development of the independence struggle across this period. The two introductory chapters set out the better known foundational years of the Indonesian nationalist movement; the first examining the impact of the conservative policies of late colonial rule, the second analysing the influence of the years under Japanese administration. Investigation of the 1945 – 1949 period begins with Chapter Three, which is concerned to identify the various conceptions of the role of the state entertained by the different political groupings. These, the authors conclude, all emphasised ‘hierarchy and leadership’: the focus was not on the individual but on the importance of the collective, where the nation was perceived as forming one large family whose interconnectedness (‘onderlinge verbondenheid’) was framed by a powerful state.

Subsequent chapters proceed to carefully analyse the chronology of the key events and disparate movements that took place between 1945 and 1950. These systematically unravel the complex detail of the internal struggles that took place as different groups attempted to take control of the process of establishing the new nation, thus underlining the ‘precarious’ nature of the Republican party’s rise to power. Chapter Four begins to lay the groundwork for this with an overview of the relatively well-known 'Bersiap', the period roughly from November 1945 to May 1946. This has been the focus of numerous Dutch accounts describing Indonesian attacks on Europeans, ‘Indonesian collaborators’, and Chinese communities in Java in the first months of the revolution. The authors, however, leave aside this Dutch narrative to instead highlight the social and political structural characteristics of the numerous ‘local revolutions’, daulat, that particularly targeted persisting elements of older colonial forms of government, thereby emphasising how the revolution was a grassroots struggle against the attempted return of Dutch colonial rule.

Chapter Six shows how leaders of the Republican faction were faced with having to deal simultaneously with two key issues: how to bring the revolutionary pemuda (youth) under control, while at the same time attempt to navigate a pathway between compromise and resistance in its negotiations with the Dutch and in its efforts to win over international support. Although the Republican Party was emerging as the leading contender to take over the former colonial state, the authors emphasise how it was being consistently challenged by more radical (and impatient) political groupings. In highlighting this political diversity, the authors demonstrate the revisionist nature of their narrative that questions any simplistic understanding of what actually constituted the ‘political community’ at this time.

Chapters Seven and Eight elaborate on this internal struggle, in part generated by the attempted return of the Dutch with British and American support. This placed increasing importance for all nationalist groups on the role of an effective military force to substantiate their goals, reinforcing the perception that the army represented a crucial instrument of state power. As well as supporting the rise to prominence of the Republican party during this early period, it set the foundations for the central role the Indonesian Army (Tentara Nasional Indonesia, TNI) played in consolidating the Republican-led state after 1949.

While attending to its diverse internal competitors, the Republican party also needed to play the ‘diplomatic card’. As Chapter Eight emphasises, the political leaders of the Republican party were confronted with what the authors describe as ‘a crisis’. In having to show the world that theirs was a viable project – that they were in control – it needed to quell the ‘urge for revolution amongst the young’, and accommodate or reject the demands of its multiple political competitors.

At the same time, the Dutch, in an attempt to curtail the territorial expansion of the Republican party’s influence – and as a strategy to retain a degree of Dutch control over Indonesia’s resources – engaged with these diverse regional and ideologically alternative groupings who nevertheless were no less passionate about Indonesian independence. Many of the groups competing with the Republicans signed up to a concept of ‘Federalism’ which is the focus of Chapter Nine. By demonstrating their concern to also constrain the ambitions of the Republican party, Federalists hoped to find a pathway to resolve the diplomatic impasse with the Netherlands. The ‘crisis’ that had now developed within the broader independence movement climaxed in a civil war (February – November 1948) described in Chapter Ten, and here the authors make explicit their view that any presumption of there being a single ‘imagined political community’ is inappropriate.

As the final substantive chapter details, in the end the Dutch government reluctantly gave way under US pressure to accommodate what was now presented as a united Republican and Federal agreement on the constitution of an independent Indonesian state. Even then, at the Roundtable Conference in The Hague in 1949, the former colonial power continued to demand outrageous terms including payment for the cost of the four years of Dutch military action that had attempted to suppress Indonesian aspirations. To make this somewhat palatable for the Indonesians the US promised to help finance the bill – a promise which it ultimately reneged on.

Schulte Nordholt and Poeze conclude that while the Revolution can be considered as having ‘brought people closer together’ in a more egalitarian and linguistically unified social order, the dominant emphasis amongst all political groupings on the importance of state formation acted to suppress the evolution of a democratic society. At the same time, they stress it is important to recognise that the revolution was not driven by ‘the development of impersonal and irresistible social processes’, but was an outcome of ‘the actions of persons and of circumstances which influenced the course of events.’. These persons apparently did not include ‘the millions of women who by and large remained invisible, both in the historical record’ and, the authors admit, ‘in our book’. Regarding this half of the Indonesian political community, the authors briefly note that ‘Apart from all the burdens they shared, they also experienced more freedom and autonomy because their menfolk were away from home’.

Fairly predictably, in their final listing of ‘winners and losers’ of the Revolution, Schulte Nordholt and Poeze nominate as ‘the winners’ the secular political and military leaders of the Republican party, and the main ’loser’, the possibility of a ‘social revolution’. Readers familiar with the scholarship of these two historians will recognise here Schulte Nordholt’s interest in the evolution of an Indonesian modernity and citizenship, and Poeze’s earlier work on Tan Malaka and the Indonesian ‘Left’. In terms of their reading of the Indonesian revolution, then, it might be argued that an ultimate conclusion to Merdeka had to await the democratic revolution that followed the collapse of the Suharto regime, which is briefly referred to the book’s epilogue.

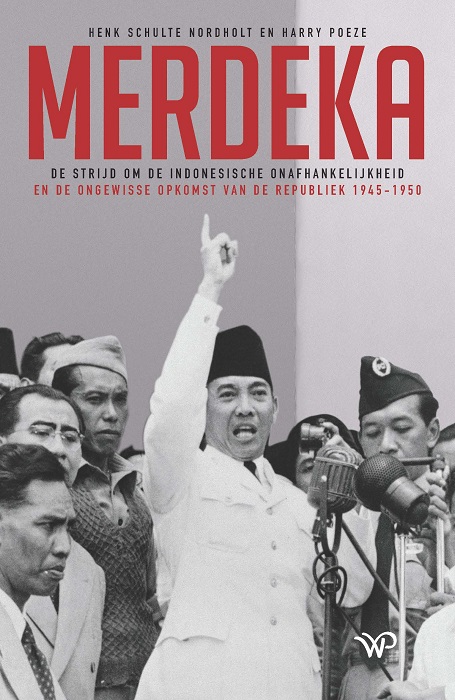

Henk Schulte Nordholt and Harry Poeze, Merdeka: De strijd om de Indonesische onafhangkelijkheid en de ongewisse opkomst van de Republiek (Merdeka: the battle for Indonesian independence and the unexpected rise of the Republic) (Walburgers Pers, 2022).

Joost Coté is Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, Monash University. This is the latest in a series of reviews he has written for Inside Indonesia of Dutch publications re-examining their colonial history. He is responsible for all translations from the original Dutch.