Salut Muhidin

In 2006 international campaigner for safe motherhood Professor Mahmoud Fathalla drew the world’s attention to the high rates of maternal deaths among women in developing countries, highlighting that 'Women are not dying because of untreatable diseases. They are dying because societies have yet to make the decision that their lives are worth saving: We have not yet valued women’s lives and health highly enough.'

Sixteen years later his comments are still relevant in many countries around the world, including Indonesia. The deaths of women while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy remain at unacceptably high levels. Professor Fathalla’s key message is that no one should be left behind in health matters, including women and mothers. To do this requires support from everyone in the community.

Too many deaths

Based on international standards Indonesia continues to record high maternal mortality rates. In 2015, it signed up to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets, which included a commitment to reach a Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) of 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030. Since then, however, little progress has been made. In the past decade, estimated MMR levels in Indonesia consistently point to between 200 and 350 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. This is in comparison with neighbouring ASEAN countries Thailand (20), Malaysia (40), Vietnam (54), and the Philippines (114).

There are further stark variations in these rates across Indonesia's many regions. Provinces in Java, Bali and western Indonesia have relatively lower MMR (less than 200 per 100,000 live births) while those in the eastern part of Indonesia have higher rates. The provinces of Gorontalo and Nusa Tenggara Timur (NTT), record 317 and 320 deaths per 100,000 live births respectively. Such a gap is both directly and indirectly related to unequal socio-political transformation, as well as changes in the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the regional populations.

The levels of maternal mortality are influenced by several factors at the personal- familial level and also at the regional level. At the personal level, factors such as household income, women’s access to education, urbanisation, household wealth and women’s health status, all play a role. Regionally, access to and the characteristics of local health services, the number of doctors working at the community health centre, the number of doctors in the village and the distance to the nearest hospital are all crucial determinants. Maternal mortality also depends on a health system’s effectiveness in addressing health risks to women during their pregnancy.

Understanding the gaps

Using a case study of maternal health in NTT province, our research attempts to provide detailed conditions about how to deal with maternal health issues in Indonesia and in this province in particular. NTT has experienced high rates of maternal mortality for several decades. In 2002 and 2012, the Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey reported MMRs as high as 554 deaths and 307 deaths per 100,000 live births, respectively. Many women, particularly in remote and rural areas, are still dying every year because of complications during pregnancy and childbirth. Most of these deaths are preventable and occur in resource-poor settings. Some women still prefer to give birth at home or to be assisted by traditional birth attendants. Giving birth at home or at non-health facilities where adequate medical emergency support is often unavailable, can lead to a higher risk of maternal death, especially in cases involving blood loss (haemorrhage).

Many of those conditions can be explained by a ‘three delays model’. It includes (i) delay in decision-making to seek care, (ii) delay in reaching a health facility and (iii) delay in receiving adequate care. The model has been widely used across less-developed countries to find potential solutions in preventing any delays that could lead to maternal and child mortality.

In the case of NTT, the first delay is relevant because receiving and accessing maternal health care or services is part of a decision-making process undertaken by a wider familial network. This decision involves not only the expectant woman and her partner, but also their extended family. Our study found that especially in cases involving those from low socioeconomic backgrounds, a lack of knowledge of the danger signs and risks in pregnancy, and awareness of the symptoms of illness, can lead to delays in making decisions if health emergencies arise.

The second delay relates to issues of accessibility, including physical distance to the closest health facility, transportation availability and affordability, and road conditions. Given the vastness of NTT province, access to health services remains a significant challenge. NTT consists of 22 districts, 3,270 villages and more than 566 islands with three main islands (Sumba, Flores and Timor). A large majority of the population (80 per cent) lives in rural areas.

The third delay is focused on the performance of the health system including factors such as health staff availability, supply, health staff competence, referral processing time and quality of care. Not all districts in Nusa Tenggara Timur have adequate health facilities, especially in rural areas.

Investing in women’s and rural health

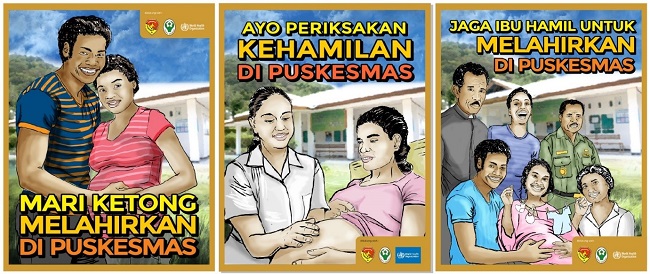

Pregnancy and related motherhood experience is not just women’s business. It needs support and assistance from the whole community, directly and indirectly. We acknowledge the strong influence of the community for good maternal health outcomes. We concluded our study by proposing a concept we have termed the ‘IBU’ program.

I is for ‘Improving the quality of maternal health care services’ by taking into account community voices and their involvement as part of strengthening existing health care services. Providing respectful care services and accessible and affordable health facilities in rural areas would be a priority to tackle preventable maternal deaths. Continuous health education should be promoted to increase the awareness of community and health care providers about health issues.

B is for ‘Building trust between communities and health care providers’ by providing opportunities for communities to be part of planning, monitoring and evaluation, and supporting initiatives such as local ownership of maternity waiting homes.

U is for ‘Understanding women’s rights and needs by ensuring access to all women and their autonomy’ by involving women to promote positive pregnancy and postnatal health outcomes. Communities and fathers should provide women with greater autonomy in making decisions about their health that would enhance better survival outcomes for themselves and their children.

Salut Muhidin is a senior lecturer at the Department of Management, Macquarie University, Sydney. His most recent research is focused on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal health, and the role of community engagement in reducing maternal and child mortality in NTT province, Indonesia.