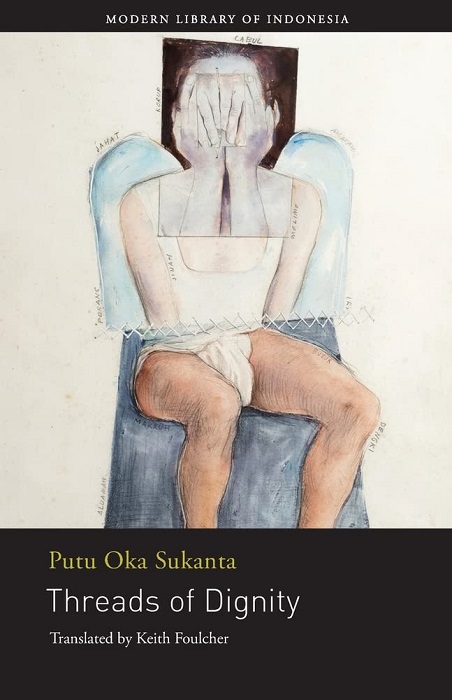

An extract from Putu Oka Sukanta's novel Threads of Dignity. Translated by Keith Foulcher.

After his detention and interrogation under torture in the wake of the “65 Affair”, Mawa finds himself a long-term political prisoner. His life in jail revolves around the loyalties and tensions among his fellow prisoners as well as the harsh reality of military power

A whistle blast just before midday was the signal for all the prisoners to return to their cells while Karjan’s body was removed from the jail. When the yard had emptied, the corporal from the front office appeared, looking as putrid as ever and walking like a tiger in pursuit of its prey. Many of the prisoners were crowded around the doors to their cells, keeping their eyes peeled in an attempt to pay their comrade their last respects. But when the commandant himself entered the block they shrunk back like snails retreating into their shells. He and his two sentries made straight for the hospital, emerging a short time later looking like they were in a hurry to get away.

In the recreation hall some of the prisoners were taking their midday nap. Some were playing card games. Mawa and a couple of others were looking out through a gap near the window.

“What are you doing that for?” said one of the card players. “If the commandant finds out, we’ll all be in for it.”

“Quiet, you!” replied one of the men squatting beside Mawa.

“Looking for trouble,” said the card player, without taking his eyes off the cards in his hand.

“Wanker.”

“Here he is,” said one of those watching. They craned their necks towards the opening and saw four men carrying a coffin, accompanied by a band of guards. The coffin bearers walked slowly, as though they wanted to give all the prisoners a chance to pay their last respects. In the end, the guards moved ahead of them, filling the silent yard with the sound of boots tapping out a regular rhythm under the midday sun. It was the sound of savagery in the midst of gentleness, power in the midst of defeat, joy in the midst of sadness, arrogance in the midst of humility. The footsteps of soldiers in total control.

But then, without warning, and totally unexpectedly—to Mawa, at least—came the sound of whistling, just as the silent procession reached a point about a third of the way across the burning concrete yard. The strong, clear notes stirred the hearts of every prisoner in the block, bringing tears to their eyes and filling them with thoughts of revenge. It was The Internationale, the Communist anthem, and everyone who heard it bowed their heads in respect. The pace of the whistling fell in with the steps of the coffin bearers, rising above the noise of the soldiers’ boots. It rose and fell, bringing with it unbearable pain but at the same time a sense of comfort and solidarity, quickening heartbeats and awakening dormant spirits.

Mawa could feel his eyes burning. He was no longer squatting by a gap in the wall, but standing straight in front of the window like someone paying homage to a fallen comrade. He didn’t care anymore what anyone might say; he was doing what he had to do. When the procession left the yard and the gates were banged shut, the noise startled him and he sank to the floor. He was still reeling with emotion.

“Why do you have to play the hero? What if the commandant finds out? You know he’ll take it out on all of us if he does. I’ve had my fill of kicks and slaps.” It was the card player again, letting fly at Mawa.

“Are you telling me I can’t pay my respects to a fallen comrade? It wasn’t just a dead dog they were carting away, you know. He was one of us.” Mawa was angry. He got to his feet and didn’t move away.

“Please yourself,” the card player sneered. “But just remember, whatever the commandant wants to know, you’re the one with the answers, okay?” he added.

“I’ll take the risk, you bugger.” Mawa was still furious.

“Come on now. Give it a rest!” Hanja and some of the others stepped in to calm the situation and divert the card player’s attention.

Mawa was still wondering who it was who’d whistled The Internationale while Karjan’s body was being carried across the cell block yard. Was it the whistler’s own initiative, or had Karjan requested it before his death? Did Karjan even know the song? That afternoon he went looking for Adar, to see what he could find out.

“It was Karjan’s spirit doing the whistling,” Borhim said quite seriously. Mawa was annoyed, but he didn’t press the matter any further. He knew there was no one in the hospital itself who could whistle like that, so it had to be someone from the cells, either the small cells or the regular-sized ones.

“Who cares?” Mawa ended up thinking. It wasn’t worth pursuing. The next day when he dropped into the hospital Untung told him that one of the guards had expressed his admiration for the whistler.

“What did he say?”

“He said ‘Hey, that rendition of Fallen Flowers was really moving,’” Untung told him. “It seems he doesn’t know the difference between The Internationale and the military’s hymn to their fallen comrades.”

On the third day after Karjan’s burial, the recreation hall was struck by disaster. Early that morning a couple of guards made an unannounced visit to the block. At the time, all the cells were locked, because it was past the time when the small-cell prisoners were allowed out to wash. One of them, an elderly man with shrunken features—not, Mawa thought, through lack of food but from the mean spirit that made him steal parcels meant for the prisoners—ordered all the men in the recreation hall to assemble outside in the yard. To a man, their hearts contracted. No one knew what was going on, but Mawa thought it must have something to do with the whistling of The Internationale three days ago. The card player came straight up to Mawa and slapped his shoulder.

“This is your doing, you know. What have you got to say for yourself now?”

Mawa didn’t reply. As he joined the crowd making its way outside, he noticed lots of eyes boring into him.

“One steps out of line and all of us pay the price,” someone said. Mawa felt it like a slap in the face, but he couldn’t do anything about it. They lined up as they were ordered, and the official launched into a speech that floated about all over the place, like a lump of shit in a river. No one had any idea where he was heading.

“The point is that in here there must be no rebellious acts in any form whatsoever. Now, I’m asking you to own up so we can get this settled quickly. Who here is planning some kind of rebellion?”

He wiped the spit that was dribbling from the corner of his lips. No one raised his hand.

“In that case, I will call the commandant. Call the commandant!” The order was directed at our chief, who ran off towards the office block. Not long after, the commandant appeared in the company of two sentries. This time he wasn’t carrying a piece of firewood but a long-handled axe.

“Is my life going to end on the blade of that axe?” Mawa wondered.

The prison yard was as silent as a grave. The commandant’s footsteps rang out like the howls of hungry jackals about to pounce on a pile of warm carcasses. Mawa shivered. His knees felt weak. The others were the same. Their faces were drained of color.

“You weren’t sent here from Sengon prison to start planning a rebellion. In Sengon you got away with all sorts of things. But it’s a different matter here. See this!” He raised the axe.

“If that axe is destined for me, I must make a stand.” The whispered words of Mawa’s heart kept his body upright.

“Who are the team leaders here?” the commandant went on.

Ten men including Mawa raised their hands.

“The rest of you step back,” shouted the commandant. Those other than the team leaders moved further away. The commandant ordered them to go back inside the cells, and they turned and crowded around the doors like patrons trying to enter a cheap cinema. When only the team leaders remained, they were ordered to form a new line.

“You want a rebellion here?”

“No, Pak,” they chorused in reply. None of them had any idea what the commandant was getting at.

“Outside, all of you!” the commandant yelled. They were all herded through the cell block gate and told to stop in front of the sentry boxes. They stood in an orderly row while the commandant started swinging his axe. Mawa looked around. Bagio, one of the team leaders who was asthmatic looked like he was having trouble breathing. He was taking shallow breaths, as though the blade of the axe flashing in the morning sunlight had narrowed his breathing tubes. Mawa looked the other way. If the axe really was meant for him, he had to have a plan. His eyes focused on the pistol at the guard’s waist.

“I’ll have to make out I’m falling over, and grab the pistol as I go down,” he resolved. Diro, who was in charge of religious matters among the prisoners in the hall, was mumbling a prayer.

“Which one of you is Hermanto?” the commandant screamed at them. Hermanto stepped forward and was immediately met by a blow from the handle end of the axe. He spun around like a chicken in its death throes before falling to his knees. But the commandant wasn’t yet finished with him. He brought the back of the axe down again on Hermanto’s kneeling frame, yelling “Just so you know, you’re not in Mahogany Jail anymore!”

He stood there with his hands on his hips, still gripping the axe in his right hand.

“Get up!”

Hermanto staggered to his feet with the last reserves of his strength, only to be hit again across his shoulders. He lost consciousness and fell face down at the commandant’s feet.

“Who else?” The commandant approached the remaining nine team leaders still lined up before him. They were deathly pale, all of them standing still with their eyes lowered. He walked up and down in front of them, studying their faces one by one. Then, without warning, he smashed his fist into the side of the sentry box, breaking it open and throwing his axe inside. Then he walked off without a glance at the men left behind. He’d achieved his purpose. He cleared his throat noisily and spat on the ground. A thick greenish phlegm. He felt in his pocket and took out a pack of clove cigarettes. As he walked towards the main office he lit a cigarette and drew the smoke deep into his lungs.