Ron Witton

Religious Pluralism in Indonesia: Threats and Opportunities for Democracy (Cornell University Press, 2021) examines the historic and contemporary dynamics of religion in Indonesia. In eleven well-researched chapters from its contributors, the book covers not only case studies across the archipelago – from Tamils in Medan to religious conflict in Sulawesi and Maluku – but also explores national trends in politics and the role of religion in Indonesia’s diplomatic statecraft.

I found the book profoundly depressing. As discussed below, chapter after chapter sets out the ways that religion is playing an increasingly constrictive and repressive role in Indonesian society.

In her introductory chapter ('The Limits of Pancasila as a Framework for Pluralism') Formichi focuses on the role played by ketuhanan (often translated as 'Belief in one god'), which is one of the Pancasila, Indonesia’s five-fold national ideology. Far from promoting tolerance and diversity, this principle has served to limit the religious expression that falls outside of the six nationally sanctioned religions: Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism.

Since the early 2000s, this restriction has been exacerbated by the increasing Sunni normativism of Indonesian Islam, leading to the persecution of such minority Islamic sects as the Ahmadis and Shi’ites. The increasingly vulnerable and persecuted situation of these groups is examined in considerable detail in Kikue Hamayotsu's chapter ('Making the Majority in the Name of Islam: Democratisation, Moderate-Radical Coalition, and Religious Intolerance in Indonesia'). The chapter leads one to consider other break-away minority religions and sects – from Seventh Day Adventists to Baptists – whose freedom relies on tolerance and protection from (often hostile) sanctioned official religious groupings.

Just as vulnerable are those who practice indigenous and animist belief systems, examined in considerable detail by Lorraine V Aragon in her chapter ('Regulating Religion and Recognising "Animist Beliefs" in Indonesian Law and Life'). Aragon makes the somewhat ironic case that while the ‘official’ religions of Indonesia are imported from abroad, there is no protection for the indigenous belief systems of Indonesia.

For those who choose not to have a religion, there is no way for them to play a meaningful part in Indonesian society. Instead, there remains the legal requirement to identify with one of the official religions in order to obtain a national identity card – an essential document for access to medical treatment, education and for participation in national life.

Moreover, to criticise religion, or to be perceived as criticising religion, leaves one vulnerable to Indonesia’s draconian blasphemy laws, to say nothing of mob violence meted out by intolerant believers whose actions rarely result in legal action by the authorities. Several chapters discuss the role played by the misuse of blasphemy laws in the 2017 jailing of Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok), who was hounded out of office as Jakarta’s governor. There was also the case of Meiliana, a mother of four who complained about the volume of a loudspeaker in a nearby mosque. Despite her husband apologising, she was jailed for 18 months on a blasphemy charge. In this atmosphere, opportunities for open discussion or to promote secularism are becoming increasingly restricted.

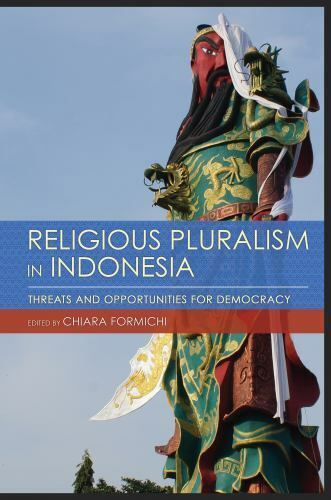

One chapter in particular documents the vulnerability of minority religions, that of Evi Lina Sutrisno ('Deity Statue Disputed: The Politicisation of Religion, Intolerance, and Local Resistance in Tuban, East Java'). In 2017 a striking 32-metre-high statue of Kwan Kong, a Confucian deity, was erected in the grounds of a Chinese temple. The statue became the target of the majority Muslim inhabitants of the town who considered such a statue to be inappropriate and disrespectful of their faith and of their feelings of Indonesian nationalism. It is a picture of this glorious statue that adorns the cover of the book. Sutrisno’s chapter includes a rather sad photo of the statue after it had been shrouded in white sheets by the temple management in an attempt to appease the local Muslim majority. However, their actions were to no avail and a final photo shows the remains of the statue after it was destroyed.

Other chapters deal with increasing Islamic Wahabi/neo-Salafi fundamentalism, often influenced from overseas and through grants by the Saudi Arabian government to Indonesian Islamic schools. One writer makes an interesting comparison to the rise of Christian fundamentalism in the West and its similar role in the spread of conservatism in politics. The Majelis Ulama Indonesia, Indonesia’s Council of Ulama, has issued fatwa against ‘liberal’ social norms ranging from seks bebas ('free sex') – including sexual relations outside of wedlock – to recognition of LGBTQI+ rights. In this, the nomination by Indonesian President Jokowi of the conservative cleric Ma’ruf Amin as his Vice-President has played a significant part in exacerbating the influence of fundamentalism on Indonesian society. Needless to say, gender equality can hardly be pursued in such an atmosphere.

In her chapter ('The Rise of Islamist Majoritarianism in Indonesia'), Sidney Jones examines a shift in Indonesia toward Muslim-first identity politics, which she terms ‘majoritarianism’. Jones argues it mirrors similar shifts in other countries, and cites Hindu nationalism in India, and Buddhist nationalism in Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand, where the dominant religion has been used to marginalise and oppress minorities, and to accelerate the decline of democracy.

Worthy of mention is the book’s attention to the recent laws promoting governmental decentralisation which have led to the instituting of shariah law in areas such as Aceh, and to the increasing difficulties for minority religions to gain permission to build houses of worship.

One cannot come away from reading the studies contained in this volume without wondering to what extent Indonesia is currently on a path to true democracy. The publication of this book at this time is surely a necessary step in recognising the need for human rights law and its enforcement to play a role in people’s daily lives and their democratic involvement in the nation.

Chiara Formichi (ed.) Religious Pluralism in Indonesia: Threats and Opportunities for Democracy, Cornell Modern Indonesia Project, Ithaca. N.Y., 2021.

Ron Witton (rwitton44@gmail.com) has worked as an academic in Australia and Indonesia and now practises as an Indonesia and Malay translator and interpreter.