Versi Bh Indonesia

Gerry van Klinken

The climate crisis is existential. Business as usual is not enough. More technology is not enough. Now is the time to begin building a new civilisation. Now is the time for the social sciences. A Manifesto addressed to Indonesian university academics.

We face today as a human race a complex of wicked problems. More and more we realise that these are not engineering problems, but political ones, even cultural ones. Politics and culture is what we social scientists do. The purpose of this Manifesto is not to be negative and say we are all doomed. It is that small measures are not enough. Almost nothing that is now on the table is enough. Only radical measures are realistic. This Manifesto is a call for radical measures to save ourselves and our planet, and to build a better future together.

This is not a ‘paper.’ It is a Manifesto! But what is a manifesto? It is not a genre taught at university in Indonesia. It should be. It is not ‘objective’ like the scientific forecast or the hypothesis that is taught there. It is hot, impatient with the present, more like a utopia. It is urgent, like a shout. But unlike a utopia, it is also sunk in history. And unlike a prophecy it is not religious but secular. Many manifestos have been artistic (the Dada Manifesto), others political (The American Declaration of Independence, The Communist Manifesto). A manifesto may warn about an apocalypse if it is not heeded. But it must also look imaginatively beyond the apocalypse. It must offer practical steps towards a better future. That is what this Manifesto wishes to do.

Why do we need one now? Because ‘business as usual’ is no longer enough. By relentlessly burning the fossil fuels we have dug out of the ground the last 200 years, humanity has created a climate crisis. Heat, the sixth great species extinction, extreme weather, coastal cities under water, even war and societal collapse. Many effects are irreversible, even if we meet the Paris goals. Even when we eventually stop burning fossil fuels, the effects will continue for thousands of years.

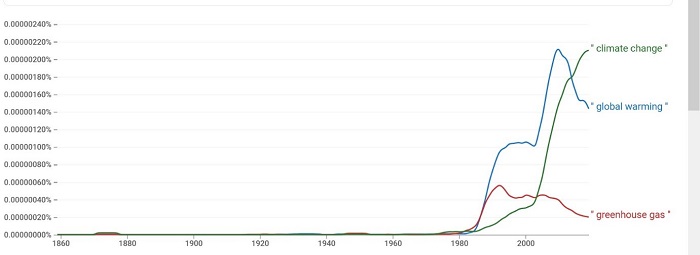

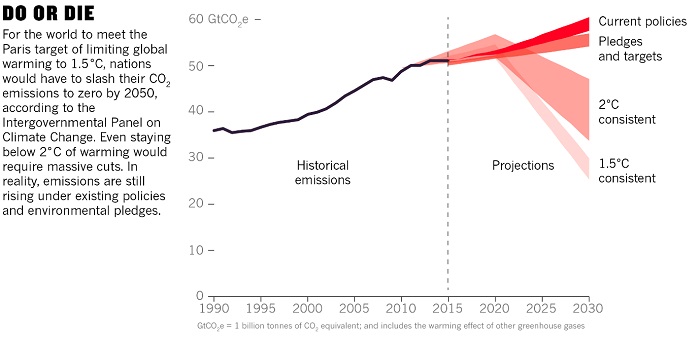

All this has been in the IPCC reports for many years. The first study of the ‘greenhouse effect’ was by Professor John Tyndall in 1859 (Figure 1). The idea of global warming has been part of a broad public discourse since 1980 (Figure 2). Yet the curve of global carbon emissions has not even begun to turn down – we are still breaking emission records (Figure 3)! ‘Business as usual’ is killing us slowly. Now UN Secretary General António Guterres says the world is ‘at the verge of the abyss;’ US President Joe Biden calls the climate crisis ‘an existential threat.’

What we are seeing is no longer routine. This is ‘the ‘unthinkable.’ It is dystopian, like in The Matrix, or Mad Max: Fury Road. Imagery of the end of the world seems appropriate - Al Qiyamah, Al-Sa’ah, the Apocalypse. Maybe we should start allowing the apocalyptic into our work. It will force us to dispense with business as usual and open our minds to big alternatives.

Why does the climate crisis not feel like a crisis?

There is a climate crisis but it does not feel relevant to our lives as social scientists. Where does this false consciousness come from? Is it intellectual inertia, inability to imagine the future? Corporate control over the academic agenda? Perhaps Indonesian social scientists have been blinded by underdevelopment dependency. As a poor country, Indonesians felt climate problems were created elsewhere. It is true that Indonesia is a victim of historical emissions in the rich West. Indonesia is more vulnerable than average to climate change due to its dependence on agriculture and fisheries and its only medium governance indicators. Rising sea-level will flood half of Jakarta and most other Indonesian cities.

Yet today’s reality is that Indonesia has become one of the world’s biggest emitters of greenhouse gases. An independent assessment recently concluded:

Indonesia was the world’s fourth largest emitter of greenhouse gases in 2015. It is the 16th biggest economy and the largest in Southeast Asia. Its emissions stem from deforestation and peatland megafires and, to a lesser extent, the burning of fossil fuels for energy. The country recently overtook Australia again to become the world’s largest exporter of thermal coal…. It plans to substantially increase its domestic coal-powered generation.

Perpetrators have responsibilities. Yet Indonesia appears to have no adequate plan to change. The independent Climate Action Tracker agency rates Indonesia’s climate plan ‘Highly Insufficient.’ If everyone was like Indonesia, the world would warm a catastrophic 3-4 degrees. (Australia rates little better: ‘Insufficient‘, implying a 2-3 degree rise). Indonesian state subsidies for coal production were worth USD 644 million in 2015, more than five times higher than subsidies for renewables.

Why is Indonesia’s climate action insufficient?

Coal subsidies are so high and mitigation actions so weak because climate-hostile business interests are at the core of government in Indonesia. (Australia is no different). Connections between top elected officials and the coal industry are explored in the 90-minute 2019 documentary Sexy Killers. A compliant mass media, well-connected to the fossil fuel industry, makes coal-fired ‘business as usual’ look like a good thing. Just as damaging as coal lobbies are palm oil interests. The deforestation they cause represents the biggest obstacle to reduced greenhouse gas reductions in Indonesia. At the moment, Indonesia is as much part of the problem as is my own country Australia.

What is to be done?

Indonesia – and Australia too - needs a radical transformation at the level of human society and politics. One that is only barely continuous with what we are used to. Sustainability is not enough. Green growth is not enough. It is our job as social scientists not to deceive. The transformation will require so much from all of us. We have a responsibility to set out a route for it.

The route depicted in this Manifesto is not dictated by fear of the apocalypse. Fear only creates paralysis and anger. It is a route towards a better future. We travel it fearlessly. Hopefully.

We are heading – thus says this Manifesto – towards an ‘ecological civilisation.’ Once we know where we are going, everything we do should look towards that end. The coming ecological civilisation gives this Manifesto its revolutionary urgency.

What is the goal?

The society of the future lives within nature. It no longer battles against nature or exploits nature – we know how badly that ended. The phrase ‘ecological civilisation‘ comes from China, whose communist party built it into its constitution in 2012. It signifies a circular economy, reduced emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants, and huge expenditure on combatting environmental damage. Pan Yue, Vice-minister of China’s State Environmental Protection Administration until 2015, was inspired by a stream of eco-socialist thinking in China going back to 1984, when the term ‘ecological civilisation’ was first coined (shengtai wenming, 生态文明). Chinese intellectuals in turn found inspiration in Russian thinking about ‘ecological culture’ in circles close to Gorbachev at the same time. The term ‘ecological civilisation’ has been open to many interpretations in China. One is that it can only become affordable once ‘industrial civilisation’ is complete. But its most radical proponents have argued that ecological civilisation involves a cultural turn that cannot be delayed. The turn is towards overcoming human alienation from each other, from nature, and from ourselves and our creativity. It means a turn towards the ‘virtues’ upon which republics have been built in the past.

In terms of economics, ecological civilisation will maintain a Steady State Economy. John Stuart Mill, the founder of modern economics, already realized in the 19th century that no economy can grow for ever. We live on a finite earth. The economy of the future cannot be capitalist because it does not grow. The steady state economy has been defined as:

…an economy with constant population and constant stock of capital, maintained by a low rate of throughput that is within the regenerative and assimilative capacities of the ecosystem. This means low birth equal to low death rates, and low production equal to low depreciation rates. Low throughput means high life expectancy for people and high durability for goods.

In 2022 it is 50 years since the Club of Rome Report shocked the world with this conclusion:

If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years. The most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.

The forces propping up capitalist business as usual remain enormous. The UN Environment Programme was until recently still writing of the ‘green economy’ as ‘an engine of growth,’ and the Biden government is doing so as we speak. Indonesia is as capitalist as any other country in the world. But on a planet where the human economy is already exceeding an ecologically sustainable ‘footprint,’ any further talk of endless growth is simply ‘insane.’

Capitalism is not simply an economic system demanding ecologically impossible non-stop growth. It is also a social system privileging ecologically wasteful and anti-social competition. Instead of competition, ecological civilisation will demonstrate a much higher degree of human collaboration than we are used to today. We can only survive as a species if we work together. ‘Eco-socialism’ is the name for these more collaborative human politics. The term is not intended to say the future will look like the Soviet Union or Cuba. Rather, it best captures the collaboration that is core business within ecological civilisation.

Ecological civilisation will be democratic. Some have asked if dictatorship is not perhaps the only form of governance that can force people off their fossil fuel addiction. But repression is likely to create more problems than it solves. In a world of greater scarcities, inequality and conflict loom. Democracy is the best conflict-resolution mechanism. Democratic eco-socialism will operate at the local, at the national, and at the international level.

Above all, ecological civilisation will be enlightened. It will be based on values. In capitalism, only greed counts. Its mantra was phrased by Margaret Thatcher: ‘There is no alternative’ to the domination of our world by multinational corporations. Herbert Marcuse called this idea ‘One-Dimensional Man.‘ The Norwegian ecological philosopher and activist Arne Naess once wrote: ‘Our culture is the only one in the history of mankind in which our culture has adjusted itself to the technology, rather than vice-versa.’ What could help to bring to life a new culture in which the ‘vice versa’ was actually the case?

Ecological civilisation rejects Margaret Thatcher’s mantra. It debates the full range of human values. By these values it measures success in achieving the good life, places obligations on its citizens, and judges bad behaviour. Environmental ethics will discover these values afresh in the classics of human civilisation. They will be values of personal and societal development, and of learning from nature; no longer simply values of consumption.

How do we get from here to there?

As academics, we have made the mistake of entrusting most of the climate mitigation and adaptation efforts to technology-oriented parts of the university. Engineers are crunching the numbers about climate impacts; public administration experts are proposing policies to transition to sustainable futures; behavioural scientists are crafting strategies to nudge consumers towards better light bulbs; engineers are designing low emission cars. Elon Musk’s battery technologies: these prestigious objects exemplify what Arne Naess called ‘shallow ecology‘ values. Elon Musk does not challenge the ‘business as usual’ that has such an iron grip on our imagination, on our way of life, on our economy, and on all our institutions. Current research on climate change is stuck because it has not gone beyond such ‘technical fixes.’ To break free from the powerful interests that trap us there, and to achieve effective economic and personal transformations, we must reconceptualize our entire social world and its natural environment. Such transformative thinking is what social sciences and the humanities do best.

Everything that we do should from now on be oriented towards that better future beyond the Abyss. I invite you to begin a conversation – many conversations! - about the multiple routes that run from here to there. In every case, there will be a mainstream and a more radical alternative route. One is premised on working forward from today’s business as usual, the other flows back from the future outlines of the ecological civilisation. Whether the field is environmental management, disaster risk reduction, sustainability, political ecology, environmental ethics, environmental philosophy, there will be a radical alternative that takes us to our destination.

Eco-politics are democratic. Yogi Setya Permana points out that the political problem is to expand our idea of democracy to include nature. Nobody is doing that yet. We need to discuss many urgent questions, among them the following. Why is the Partai Hijau Indonesia too small even to enter the elections? How radical does a movement for ecological civilisation have to be? How political? What relevance does the 1945 Revolution have for ecological civilisation in Indonesia? Who are the heroes of ecological civilisation we may emulate? What are the bases for collaboration within existing social movements such as women’s movements? What to do about the gap between those who want to pursue lifestyle politics (such as sustainable retailing) and others who engage in extra-parliamentary protest politics (Extinction Rebellion)? What about community-oriented vs state-oriented activism? Does the developing world offer special opportunities for more radical global action?

Many will say this is a hopelessly idealistic project, when it seems that most people are happy with the consumerist capitalist lifestyle. No doubt it is. When I was young, we had a slogan: ‘Be realistic, demand the impossible!’ That would be a good one to revive. Can the university break out of the grip of the corporate interests? I saw a poster at a climate rally that said: ‘It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.’ Can we and our universities help the world to imagine better? Can we show our society practical steps beyond the Abyss toward a better future?

Gerry van Klinken (klinken@kitlv.nl) is honorary professor at the University of Queensland, the University of Amsterdam, and KITLV. The published Indonesian version (‘Demokrasi tanpa Demos‘, 2021) has an extra reading list. This paper was prepared for an online seminar of the Forum 100 Ilmuwan Sosial Politik, LP3ES, World Environment Day, 5 June 2021.