Geger Riyanto

The coastal township of Parigi was not originally as dependent on yellowfin tuna as it is today. Like many other villages throughout Seram, central Maluku, it was settled by those who came to the island to cultivate their own copra plantations and farm other forest commodities. In the first half of the twentieth century people began to move there due to the skyrocketing prices of commodities.

If one goes to Parigi nowadays, one thing that she will immediately notice are the coconut trees. They are everywhere. The village itself was formerly a copra plantation. As more people started to settle, houses were built and the plantation slowly turned into a proper settlement.

Since the earliest days of the settlement Parigi inhabitants have relied on fishing as a source of food and income. Fishermen mainly caught skipjack tuna, which they used for their own consumption or sold in other settlements.

Along with tending commodity and staple crops, fishing is an important activity sustaining the livelihoods of Parigi villagers. Their everyday routines revolve around fishing. They will sail out to sea at daybreak. When they return, their wives will already be waiting on the shore to help carry their equipment and bring in the catch. At home, they will converse with fellow fishermen about fishing and prepare their tools. Fishermen form groups to assemble fish traps that cannot be assembled by a single individual. As a group, they maintain the regulation of fishing rules.

The centrality of fishery in the lives of the people of Parigi grew even more pronounced with the onset of the boom of yellowfin tuna in the mid-2000s. Buyers of yellowfin tuna started to appear offering very good prices for their catches. In the decade after the boom began, Parigi experienced massive population growth. At the end of the 1990s, the population was approximately 300 residents. By 2015, it had increased to almost 1300.

The village enjoyed an unprecedented period of prosperity due to the boom. New houses were built and old ones were renovated. Fishermen bought themselves boats of higher quality. Parents sent their youngsters to college and university.

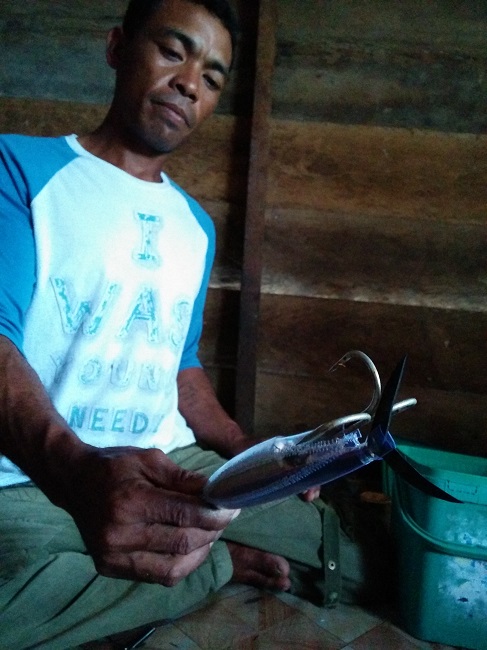

When I returned to Parigi in 2018, the situation had begun to change. Fishermen could still catch yellowfin tuna, but the number could not compare to what it had been several years ago. At a glance, this was seemingly caused by the change in their fishing method. Normal practice was to use a bait of mock flying fish controlled through a kite to catch yellowfin tuna which swam at the surface. Now, the fishers are only able to catch the tuna by lowering a bait of squid to the lower part of the ocean. The latter fishing method takes much more time.

Why is yellowfin tuna getting scarcer at the ocean’s surface? Research has argued that this is one of the immediate effects of global warming.

Fish populations are in fact wholly changing in North Seram. Even the skipjack tuna catch dwindled, and those who were accustomed to eating a single fish for their family meal had to adjust.

People started to accumulate debts as their catches decreased, yet they relied on money now more than ever. They stopped renovating their houses midway. They tried what they could to attract the fish back, including making new fish traps or roaming further out to sea, both of which would cost them dearly if they still could not catch more fish.

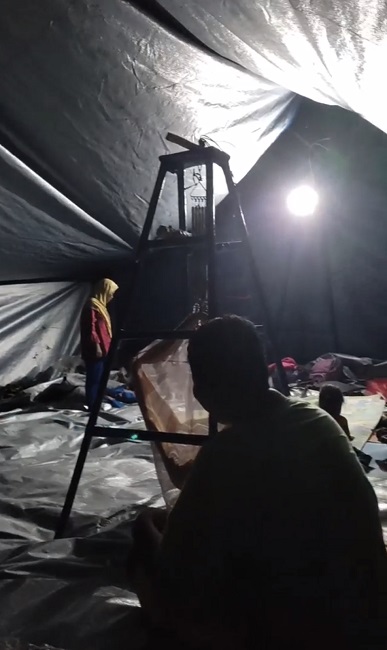

On 22 February, 2022, a storm surge hit Parigi. Tidal waves from the ocean wrecked boats and houses. Storm surges had happened time and again, but this one was different. Nothing had ever been as ravaging as this one. ‘I have never seen anything like this in my lifetime,’ said Jhoko, a young Parigi fisherman to me.

From the videos my Parigi friends sent me, villagers can be seen staring helplessly at the devastation wrought by the violent waves. They scream to fishermen who are still trying to save their boats, warning that they could be washed away by the waves. Even when the ocean had calmed, villagers whose houses were next to the shore did not want to go back to their homes. They fled to the high ground and were afraid of a worse storm surge.

The Parigi villagers have returned to their homes now. However, nobody can tell what will happen to this coastal community next. Amidst our incessantly warming world, there is only uncertainty for people whose livelihoods depends on the ocean.

Geger Riyanto (geger255@gmail.com) is a PhD student in Heidelberg, Germany. The author also wrote the accompanying article on the fishing community in Parigi.