Ecological civilisation in Indonesia

Yogi Setya Permana & Gerry van Klinken

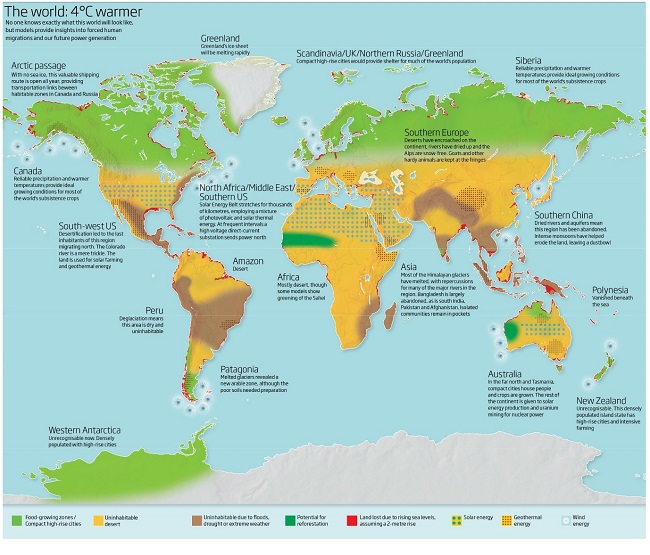

It remains possible that by 2100 the globe will be four degrees hotter. This map is based on research presented at a conference about that terrifying possibility, held in 2009. It shows deserts everywhere! UN Secretary General António Guterres says the world is ‘at the verge of the abyss.’ Yet we still cannot imagine the world beyond the abyss.

The Melbourne philosopher Arran Gare says ‘sustainable development’ has failed, because it conceives the economy as something separate from nature. It allows us to continue to exploit nature. To win the war for survival, global humanity now needs to embrace ‘ecological civilisation.’ This does not yet exist, even in China where the term originated. It is a utopia, in which people no longer do battle with nature, and cooperate with each other, for the sake of the long-term future.

What does that utopia look like? How do we go from today to that better future? The idea for a special edition on Ecological Civilisation arose from a Manifesto that one of us (GvK) presented on World Environment Day, 5 June 2021, to an online forum of Indonesian social scientists. That Manifesto appeared in a book, and is republished in this edition. 'Everything that we do should from now on be oriented towards that better future beyond the Abyss', it urges. 'I invite you to begin a conversation – many conversations! - about the multiple routes that run from here to there. In every case, there will be a mainstream and a more radical alternative route. One is premised on working forward from today's business as usual, the other flows back from the future outlines of the ecological civilisation.'

This edition wants to be the start of some of these conversations. It will always be looking for the radical alternative. We approached writers already engaged in transformative movements towards an ecological civilisation in Indonesia. We asked them to write how they saw that better future beyond the Abyss, and how they thought Indonesians could get there.

Any movement for ecological civilisation is personal as well as political. Deep ecology re-connects humans with nature in ways that have much in common with religion. Ulil Amri's piece on the 'green' religious schools, pesantren, which teach new attitudes to nature, opens doors to transformed personal values.

Other articles here deal with the politics of ecological civilisation. They all urge a new way of doing politics. Perhaps the most radical among them is by two feminists, Haris Retno Susmiyati and Siti Maimunah. Their online conversation shows that existing women’s movements can provide a basis for collaboration towards ecological civilisation. Connections between the women´s movement, the environment, the history of capitalism in Indonesia, and climate change, are close. The essay by Gerry van Klinken on ‘eco-socialism’ argues that Indonesia´s 1945 Revolution is a unique historical asset. It could even inspire its neighbours in Australia in the intensifying fight for climate justice. Capitalism kills. New structures of power are necessary that enhance life rather than destroying it.

Around the world, some green movements work with the central state because it is effective. The Indonesian Green Party (Partai Hijau Indonesia) is one of them – although a wide-ranging interview with its leaders in this edition shows how dispiriting and unequal this struggle is in the present context.

Others abandon the central state because it is itself part of the problem. They work with local communities instead. Based on experience in flood-prone Semarang, Eka Handriana argues that only direct democracy rooted in the ‘bio-region’ of their coastal ecology can lead to harmonious relations between humans and nature. Farwiza Farhan and Prio Sambodho, meanwhile, describe patrols by women rangers in Aceh that have significantly slowed illegal logging in the precious Mount Leuser National Park. Geger Riyanto visits a fishing village in Maluku where climate change is already causing catches to decline. These fishers are the most vulnerable to global climate breakdown, yet they seem to have little idea why this is happening to them. This raises questions about the adequacy of indigenous knowledge to cope with the fate of the rural poor in a climate-ravaged future. His photo essay beautifully illustrates daily life by the sea.

Each one of these pieces challenges a stereotype in some way. Each rises above today's nihilistic 'anti-politics', and shows that a better way is possible. Cynics might say to each one that their utopias are 'not realistic'. The sociologist C Wright Mills, in a different context, once called such people 'crackpot realists'. Their ideas make sense on their own terms, but when considered from the point of view of the entire globe they are completely nuts. He had an answer to such people. '[P]recisely what they call utopian is now the condition of human survival,’ he wrote. Che Guevara once said something similar: 'Be realistic, demand the impossible!'

Eco-politics are transformative. Our civilisation is addicted to fossil fuels. To kick the habit and achieve ecological civilisation, only a radical democratic movement will do. The political problem is to expand our idea of democracy to include nature. Nobody is doing that yet.

So many questions still remain. Perhaps in future we can do an edition on the way higher education should renew itself, from the ‘business as usual’ that is now worse than useless, towards nurturing intellectual leaders of ecological civilisation. Every discipline ought to be transformed, from economics to engineering, from political science to physics.

Yogi Setya Permana (permana@kitlv.nl) is a PhD researcher within the KITLV - University Leiden research agenda on climate governance. Gerry van Klinken (klinken@kitlv.nl) is honorary professor of Southeast Asian history at the University of Queensland, KITLV, and the University of Amsterdam.