Versi Bh. Indonesia

Anton Muhajir

This year’s new year celebrations at Pantai Segara, Sanur, were unusually quiet. A sound system had been set up, but remained silent. Wooden chairs were flipped upside down and draped over tables. Customers at the beachside restaurants wandered home early, leaving this once buzzing tourist area quiet.

About 15 minutes prior to the arrival of the new year, the atmosphere was still lively. It was busy with locals. The waiters were busy delivering their orders. The DJ played the music beneath flashing lights.

But the party was brought to an abrupt halt. Police, together with the local pecalang – one of the local Balinese security enforcers – arrived on the scene. They asked the managers of the café to shut the party down.

‘Sorry, sir, we can’t do it now. How will get people to pay?’, said the café’s owner.

‘These are the rules. The pandemic is still happening. We’re not allowed to gather in large numbers,’ said the pecalang.

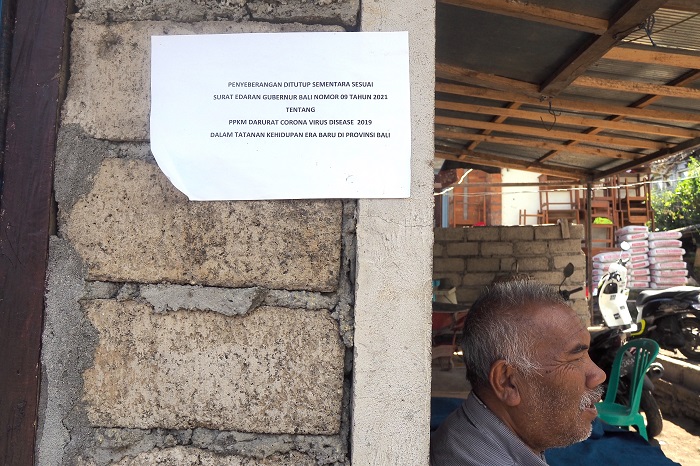

This joint operation used three regulations to prevent the New Year’s Eve party from taking place. There are three regulations regarding the holding of Christmas celebrations (2021) and New Year’s Eve (2021-22). These are the Internal Affairs Minister’s Instruction No.62, 2021; the Tourism and Creative Economy’s Minister’s Bill No.SE/2/M-K/2021 and the Balinese Governor’s Bill No.20 of 2021.

The three bills state the same thing: all businesses and tourist destinations are banned from holding New Year’s celebrations, either inside or outside. This includes the holding of parades, firecracker parties and fireworks.

So, there was no room for discussion. The manager asked the party-goers to return home. One-by-one they got up from their tables and left. The restaurant, which had only moments earlier been lively, quickly became quiet. The New Year’s party ended without a bang.

In other places, however, some people were still celebrating in a somewhat constrained manner, including at the beach next to one of the oldest hotels in Bali – the Grand Inna Bali Beach. Some of the guests at this hotel, which is owned by the Indonesian government and built in 1963, were setting off fireworks on the beach.

The fireworks launched into the dark, damp night air. There was a brief flash in the sky of colourful sparks. Then, everything was dark and quiet once more. After two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, the island of Bali still couldn’t see the light at the end of the tunnel.

Dramatic decline

The pandemic has hit Bali harder than other provinces of Indonesia. Since the first case of COVID-19 was identified in Indonesia in March 2020, the usually lively tourist atmosphere of Bali has dropped off dramatically. Tourism, which forms the basis of the Balinese economy, has died.

During the entire year of 2021, there were only 51 visits by foreign tourists to Bali. This figure, according to the Central Statistics Bureau, was a 99.95% drop off compared to the previous year. Between January-November 2020, there was around one million foreign tourists who visited Bali. This figure, was 83.26% lower than the previous year.

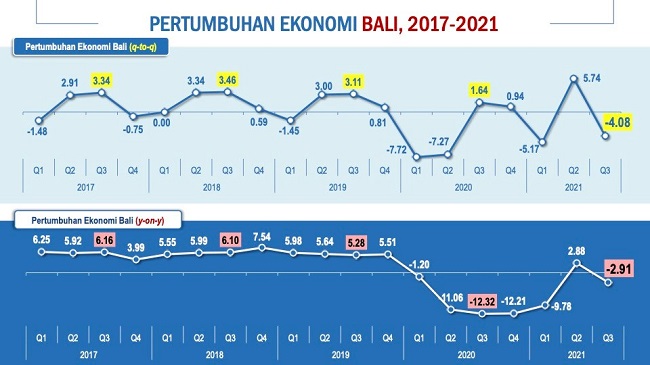

Data from the last two years shows the impact of the Pandemic. At least five million tourists were visiting Bali prior to the Pandemic: 5.7 million in 2017; 6 million in 2018 and 6.2 million in 2019. Without tourists coming to Bali, the Island’s economy is like a roller coaster after it has reached its highest point: it descends dramatically. The growth of the Balinese economy, which had been steadily declining – 6.16% in 2017, 6.10 in 2018 to 5.28 in 2019 – then fell off a cliff in 2020, at -12.32% and -2.91 in 2021.

At first glance, this data doesn’t lie. The tourist hotspots throughout Bali have remained totally dead. Many of the hotels, restaurants, cafes and souvenir shops in Kuta and Seminyak are still closed. Their doors are locked as the dust gathers.

It’s not only like this in southern Bali, but in other parts of Bali also. For example, Pantai Amed, which is usually busy with foreign tourists, was completely quiet. The number of foreign tourists could be counted on one hand. When in fact, the end of the year, like the middle of the year, is one of the peak seasons of tourist visits to Bali.

‘For the last two years, we’ve had no guests. I think I’m just going to rent it out,’ said Wayan Miskin, one of the managers of a hotel in Amed.

Relative success

Bali’s tourism sector is yet to recover from the impact of the pandemic which cannot be separated from local, national and global developments.

The management of COVID-19 in Indonesia, including Bali specifically, has been relatively successful. The spread of the virus has been relatively contained. On the 31st December 2021, for example, the increase of Covid-19 cases throughout Indonesia was ‘only’ 180 cases. This is well below the number of cases at the height of the second wave on 15th July 2021 which reached 56,757 in one day.

The situation in Bali is similar. At the start of the year, in early January 2022, there were no recorded cases. The previous August, though, there was more than 1,900 reported cases.

After the situation had been brought under control, vaccination rates were also increasing. In the first week of January 2022, the Balinese government had vaccinated approximately 3.5 million residents of Bali – more than the initial target of 3.4 million. As many as 3.1million second doses had been distributed, or roughly 91.35%.

Despite the stabilisation of the pandemic, tourists were yet to return to the island. ‘The situation hasn’t yet recovered, but whatever the case, life has to go on,’ said Wayan Willy, a driver working in the tourism industry.

Willy runs a tourist agency with some friends. They serve foreign and domestic tourists in Bali. Before the pandemic, most of their clients were from overseas. But, nowadays, they rely on domestic tourists. Their clients are few and far between.

The situation is the same in Kuta. According to the BPS, last October, the occupation of hotels was only 17.73%. This figure was far below what is required for a hotel to stay in operation.

‘The breakeven point for a hotel is 40% occupation. If it is lower than 10%, it is not even possible to cover the operational costs,’ said IGN Rai Suryawijaya, the Head of the Tourism, Restaurants and Hotel Association of Indonesia (PHRI) of Kabupaten Badung.

According to Rai, this is the lowest point in Balinese tourism. Bali has been through two bombings (2002 and 2005) and a volcanic eruption in 2017. In these cases, however, thanks to governmental support and the international community, Bali has been able to recover quickly.

‘Those situations were different. Nowadays, everyone is having difficulty, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic.’

Up and down

Like the title of George Orwell’s first novel, Down and Out in Paris and London, so too are the conditions of the tourism industry in Bali. The same applies to the governmental policies. The local and national governments have to tried to resuscitate the industry through various means. In mid-September 2020, when the number of COVID-19 cases was still rising, the national government invited social media influencers to help promote tourism in Bali.

Through the program, We Love Bali, the Bali Tourism Bureau invited 44,000 social media users to come to Bali. They were expected to promote their visit to Bali based on its cleanliness, health, safety and its environmental qualities.

One year later, the national government also initiated the program, Working from Bali (WFB). Government officials, otherwise based in Jakarta, held some of their meetings in Bali. The large and luxurious hotels in the elite areas of Nusa Dua and Kuta were filled with civil servants from Jakarta, at a time when COVID-19 cases in Jakarta were skyrocketing.

Made Rentin, Secretary of the COVID-19 Task Force pointed to this policy as the reason for the increase in COVID-19 cases in Bali in the middle of 2021. After being relatively contained, cases on the island took off and reached a peak in August 2021. The WFB program was scrapped after the number of cases in Bali continued to increase.

When the situation started to improve, the government tried once more to encourage tourists to visit Bali. On 14 October 2021, the national government re-opened Bali for international flights. President Joko Widodo himself made the announcement. Previously, owing to the pandemic, international flights were only permitted to land at Soekarno Hatta airport in Cengkareng (Banten) and Sam Ratulangi Airport, Manado (Northern Sulawesi).

The reopening of the airport for international flights marked a new moment of hope for Bali. I Wayan Koster, the Governor of Bali, was optimistic that the opening of international flights would bring 40,000 foreign tourists to Bali. According to Koster, hotel rooms were being booked.

But Koster’s hopes weren’t realised. The international re-opening of flights had no impact. Still, the number of foreign tourists could be counted on one hand.

‘Koster talks rubbish,’ said Made Suarta a ride share driver.

Same old, same old

According to Suarta, the empty rhetoric of the government in reviving the Balinese economy is also evident in the government’s plan, Mapping the New Balinese Economy (Peta Jalan Ekonomi Kerthi Bali Menuju Bali Era Baru). President Widodo launched the plan on 3 December 2021.

In this plan, the Indonesian government offered a new vision of Bali as green, resilient and prosperous. This concept is a reflection of the Balinese economic situation which is highly dependent on tourism. There are six basic strategies, including that of ‘Productive Bali’, which incorporates agricultural revitalisation, fisheries and marine tourism.

According to the plan, Bali's economy is targeted to grow 7.7% by 2045. This transformation is aimed at increasing the agricultural sector by 5.4% in the same year.

However, hoping that Bali can create a new economic sector other than that of tourism is a daydream. ‘The government doesn’t have another concept at the moment,’ says Willy. The evidence is in the Mapping the New Balinese Economy plan. The government, has, at the same time, introduced the Tourism Development Plan of Ubud, Tegalalang and Payangan (Ulapan). Tourism, yet again.

The launch of the roadmap Mapping the New Balinese Economy took place on Serangan Island; an island reclaimed during the New Order era, between 1994-1998. At that time, activists protested against island reclamation in the area to the south of Denpasar. Serangan became a monument to the failure of mass tourism development in Bali.

Now, this island has become the site of the launch of new economic jargon from the government about the recovery of the tourism sector. As such, for critically engaged citizens of Bali, including Wayan Willy and Made Suarta, the government hasn’t learned from alternative economic sources apart from mass tourism.

Nyoman Sukma Arida, of the Tourism Faculty at Udayana University in Denpasar, states that Bali has to be prepared to face new trends in tourism once the pandemic is over. ‘Bali has to create a high-quality tourism industry connected with village-life, the environment and health,’ said the PhD graduate from Gadjah Mada University of Yogyakarta.

If not, according to Sukma, the Balinese government will only repeat the mistakes in looking for alternatives beyond mass tourism. In fact, it is proven that mass tourism is a highly precarious industry. It is vulnerable to fluctuating global circumstances.

‘Tourism in Bali is like a sand castle. It is beautiful, but it can be washed away by the waves,’ added Willy.

Anton Muhajir (antonemus@disroot.org) is a Bali-based freelance journalist and blogger.