Sophie Chao

Over half of the world’s palm oil supplies are sourced from Indonesia, where monocrop oil palm plantations today cover an estimated 16.38 million hectares of land. The expansion of oil palm monocrops is a key driver of deforestation and biodiversity loss across the Indonesian archipelago and the tropics more broadly. It is also a major contributor to climate change and global warming at a planetary scale. But what shape does everyday life take for people who inhabit the plantation nexus? What kinds of subjects are formed under plantation regimes? And why are plantations still expanding despite their abundantly documented negative impacts on rural communities’ lands and livelihoods?

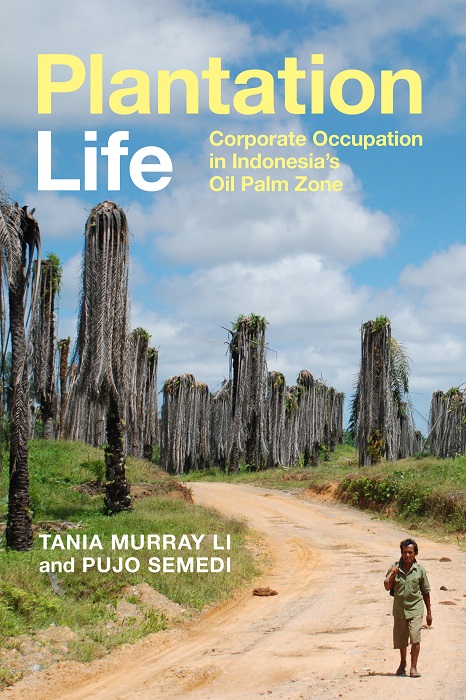

These questions lie at the heart of Plantation Life, an ethnographic account of the social, economic, affective, material, and political relations generated through the corporate occupation of Indonesia’s oil palm plantation zone. Co-written by Canada-based British anthropologist Tania Murray Li and Java-based Indonesian anthropologist Pujo Semedi, the book is grounded in field research and interviews conducted by the authors and a cohort of over one hundred students in two plantations in Tanjung, West Kalimantan – the one state-owned (Natco) and the other private (Priva).

The perspectives encompassed in this work stem from an array of actors who are each implicated in, and affected by, plantation regimes – from concession managers and oil palm workers, to government representatives, NGOs, research organisations, and communities inhabiting the peripheries of monocrop concessions. The authors deftly analyse these perspectives through the conjoined lens of political economy and political technology to examine how land, labor, and capital are assembled to generate profit for some and poverty for others, and how subjects are produced and territories and populations are governed within the plantation nexus. In doing so, they foreground the ‘world-making’ properties of the plantation as it enrolls differently situated protagonists in the generation of new configurations of life and order.

This analysis brings to the fore a set of recurring motifs in the formation of plantation life. One is the identity of the corporate plantation as an occupying force that violently invades and reconfigures practices, processes, and relations within and beyond the plantation site. Another is the rootedness of the plantation in colonial-racial logics that remain firmly embedded within contemporary Indonesian law and political discourse. Another is the crystallisation of multiple, extractive regimes within the plantation form – palm oil as a global market commodity, financial profit for capitalist conglomerates, economic revenue for the Indonesian state, and unearned income from people who are forced into a way of life they cannot control.

Each of these dimensions of plantation life perpetuates in state-sanctioned and legalised forms the coercive violence of the New Order era through dispersed and diverse networks and practices of ‘corporate harm’. These practices of corporate harm include the overtaking of vast swaths of land without due consultation, the systemic entrenchment of mafia practices, the destruction of villagers’ rice and rubber fields, the reduction of formerly independent farmers to near-landlessness, the abandonment of those who fail to support or who obstruct plantation projects, and the degrading of citizenship among surrounding communities.

The formation of plantation life, according to Li and Semedi, is in turn profoundly entangled with an entrenched and deceptive plantation logic – namely, the state-endorsed promotion of massive, modern plantation developments to feed the nation and the world. This logic, however, obscures the centrality of political economy, political technology, and the impunity of Indonesia’s political milieu in driving and sustaining the hegemony of the plantation form. At the same time, the hegemony of plantation regimes is plagued with awkwardly coexistent contradictions.

Plantations, the authors note (p. 26), are at once rational bureaucratic machines and invasive plundering giants. Plantation managers are both technicians and thieves. The promises of wealth and prosperity that accompany plantation developments are both true and false. The monocrop environment is orderly and clean, but also teeming with pollution and parasites. The material fixity and endurance of the plantation is also paired with contingency and fragility as workers and farmers push back against their dispossession through theft, extortion, calls for recognition and compensation, the forging of new desires and dispositions, the expression of anger and betrayal, and the imagination of different kinds of futures for generations to come. Many of these individuals know there is something deeply wrong with plantation life – but they have learned to tolerate and navigate this life in order to survive.

Among the most insightful and thought-provoking contributions of Plantation Life is its argument for why monocrop plantations continue to proliferate across Indonesia despite ongoing calls for legal reform, sustainable corporate practices, and for some, the outright abolition of the plantation form. Li and Semedi identify the roots of plantation endurance and expansion in the licensing of corporate harms as an unfortunate but necessary side-effect of the state-sanctioned mandate of corporations to bring prosperity to remote peoples and provinces. In other words, the social, environmental, and economic harms wrought by agroindustrial projects are normalised as an anticipated but unacknowledged cost of plantation operations that are politically favored, protected, and therefore ‘not permitted to fail’ (p. 183). And yet ironically, Indonesian farmers have repeatedly shown that they do not require corporations to enable or achieve the production of global market crops.

For all the enduring stereotypes of rural peasantry as technically inept and therefore necessitating corporate presence, Indonesian villagers have for over three centuries demonstrated their willingness and ability to engage in cash crop cultivation on their own, provided adequate access to infrastructure is made available to them. Corporations, in other words, are not technically necessary to achieving the economic and developmental ends of the plantation industry.

Two other key strengths distinguish Plantation Life’s contributions to social scientific studies of the plantation form. One is the work’s nuanced attention to the specificity of plantation formations in space and time and the insights they reveal about corporate capitalism’s situated workings. As Li and Semedi caution, the use of the label ‘plantation’ is problematic as it implies a false equivalence between different plantation zones that are each the product of particular historical, social, economic, and political terrains and trajectories (p. 21). Attending to the specificity of particular plantation forms, the authors note, does not pre-empt the possibility of comparative research on plantation life in other times and places. Rather, it invites nuanced analyses of the factors that produce similarities and differences across different plantation formations, such as extant political systems, legal architectures, labor regimes, tenurial arrangements, ecosystemic contexts, and the effects and affordances of cash crops themselves.

The second strength of Plantation Life lies in its distinctive methodological approach, discussed in an Appendix titled ‘Collaborative Practices’. In this illuminating section, Li and Semedi offer a detailed genealogy of their collaborative endeavours with each other and with their student cohorts, from the initial planning of the research to the finalisation of the written manuscript. They highlight generative differences in their respective approaches to anthropological fieldwork and writing. They explain how they sought to overcome the entrenched colonial relationship between foreign and native researchers. They identify what was learned by each party in the process of writing together, in person and virtually. They also demonstrate how challenges in translation from English to Bahasa Indonesia and back helped to generate a deeper analysis of the book’s key ideas, concepts, and arguments. In these and other respects, the methodology that anchors Plantation Life compellingly illustrates the intellectual possibilities generated by decolonial, collaborative Global North-South research in the current era.

Written in a clear and compelling style, and rich in its empirical and conceptual insights on the plantation form, Plantation Life is essential reading for anyone with an interest in tropical environments and societies, agrarian relations, colonial-capitalist regimes, and the political economy of plantation systems.

Tania Murray Li, Pujo Semedi, Plantation Life: Corporate Occupation in Indonesia’s Oil Palm Zone, Durham: Duke University Press, 2021.

Sophie Chao (sophie.chao@sydney.edu.au) is a Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) Fellow and Lecturer in Anthropology at the University of Sydney. Her research explores the intersections of Indigeneity, ecology, capitalism, health, and justice in the Pacific. For more information, please visit www.morethanhumanworlds.com.