The role of cyber troops in promoting Indonesia’s controversial pro-business bill

Lailuddin Mufti & Pradipa P. Rasidi

For an activist like Dharta, it was not easy to reminisce on last year’s Omnibus Law protest. Back then, he actually advised against the protest, seeing that the protestors were up against a formidable challenge. Within the government, political consensus on the Omnibus Law on Job Creation had long been consolidated, Dharta explained – it was a done deal. Moreover, he said, ‘on social media all kinds of buzzers were assaulting us from all sides. So, I thought: that’s that.’ The concurrence of government consolidation and concerted attacks by pro-government cyber troops – including ‘buzzers’ and influencers – led Dharta to believe they had lost this battle before their protest had properly started.

Still, the protest proceeded, and it became a massive expression of people’s anger at the parliament’s hastened passing of the controversial law, late at night on 5 October 2020.

The Omnibus Law on Job Creation amended 73 laws to create more efficient policy for business investment. According to President Joko Widodo, or ‘Jokowi’, it tackled investment constraints, employment problems and the middle-income trap to stimulate Indonesia’s economic growth. But according to critics, it would merely benefit big corporations while harming the working class and the environment.

In the week after the law’s passing, academics, students, labourers and activists staged protests in at least 30 cities across Indonesia. On social media, netizens shared videos, infographics and memes in protest. Tens of thousands of K-poppers (Korean pop fans, often teenagers) helped trend protest hashtags on Twitter and TikTok, inviting broad public participation in the protest.

However, just as Dharta feared, the government’s response was swift and solid. While police and army troops violently dispersed the street demonstrations, on social media, masses of cyber troops were mobilised to crush the online protests. Opposition parties, such as the Democratic Party, also used cyber troops to counter the government. But neither those parties nor the protesters were a match for the government’s concerted efforts not just to quell the protest, but also to sell to the public the narrative that the Omnibus Law is a blessing for Indonesia’s economy.

A cyber troop's job

When the controversy over the Omnibus Law on Job Creation erupted, cyber troops, known also as ‘buzzers’, were a well-established phenomenon in Indonesia. The cyber troop operations to promote the Omnibus Law were led by highly experienced buzzers. One of them was Abimanyu, a key coordinator of the effort. In his two-storey house with a large garage, he shared his experiences as a seasoned figure in the world of buzzers.

Abimanyu originally supported Jokowi and his running mate Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, or ‘Ahok’, in the 2012 Jakarta gubernatorial election. Since he was not a legal resident of Jakarta, he could not vote in that election. But, driven by the charismatic figure of Jokowi, Abimanyu would fiercely defend him in debates on social media.

Abimanyu’s ‘militancy’ on social media drew the attention of a group called Jasmev, the Jokowi-Ahok Social Media Volunteers, who contributed to the election campaign through a well-crafted and successful social media push. Soon, this group formally recruited Abimanyu, and in the run-up to the 2014 presidential election, he transformed into an active social media campaigner for Jokowi.

He recalled that the presidential campaign was efficiently organised: the volunteers gathered in WhatsApp groups to receive content to share on social media. Abimanyu also learned to operate small buzzer accounts and how to gain followers to make his main accounts ‘big’. Over the years – as he went on campaigning for Ahok in the 2017 Jakarta election and then for Jokowi in the 2019 presidential election – he learned all the tricks of the trade.

Initially, Abimanyu was not counting on rewards. But when he learned that other volunteers were getting paid, he also asked for compensation, and in 2018, he got on the payroll.

Today, he still works to support Jokowi’s policies and attack his political rivals, such as Anies Baswedan, the current Jakarta governor and potential candidate for the 2024 presential election. These days, they are paid per team, Abimanyu said; each large team of volunteers is gathered into smaller groups based on the issue they are trying to raise or fight against. A single person can volunteer to take on several issues at once, if they prove they can handle it. They are paid based on those issues.

One of those issues was the Omnibus Law on Job Creation. Abimanyu was entrusted to be a coordinator in this big operation by someone close to a politician. According to Abimanyu, this contact person, or ‘broker’, refused to reveal the politician’s identity. When asked about this ‘Mr. X’, the broker said: ‘Oh shut up, you’ll get your cash, now get to work!’ The authors cannot know for sure whether Abimanyu was truly left in the dark about those funding the Omnibus Law operation. However, he did not hesitate to share with us the names of ‘Mr. Xs’ funding other operations. What he revealed indicates that the higher the stakes, the more secretive the operation.

As a coordinator, Abimanyu received monthly funding for his team; it was up to him how to divide it among the team members. For this operation, he received Rp.25.000.000 per month. ‘So, that’s 15 million for the buzzers, 10 million for the content creators.’ He paid each buzzer Rp.500.000 to Rp.1.000.000, depending on the number of social media platforms they operated, i.e., whether it was just Twitter or also Facebook and Instagram. To avoid suspicion from the anti-money laundering agency, Abimanyu explained, cash flows were usually limited to Rp.1.000.000 per transfer. His team members were contracted every three months. The contract could be extended if there was an additional task or terminated if the task was considered completed.

Abimanyu’s job was to make sure that his team members posted content every day, ‘Fifteen on Twitter, five on Facebook. Every day you know, for at least one month’. If someone failed to meet the daily target, Abimanyu would chase them down or be reprimanded himself by the broker. ‘Those upstairs will say, whoa, why isn’t there a post? They usually check’, he said. Abimanyu regularly sent reports about his team’s work to ‘those upstairs’ .

A concerted campaign

But buzzers weren’t the only ones mobilised to promote the Omnibus Law on Job Creation. In August 2020, 21 famous influencers and artists – including popular actor and jazz singer Ardhito Pramono, entrepreneur and YouTube talk show host Gofar Hilman, and dangdut singer and luxury lifestyle influencer Inul Daratista were all found to have received payments to ‘sell’ the Omnibus Law on their social media, using the hashtag #IndonesiaButuhKerja (Indonesia needs jobs). Once exposed, some of these influencers quickly denied any knowledge of the source of the hashtag (or the payment), claiming they had no idea it was linked to the Omnibus Law. The presidential office also denied any government involvement. Apparently, the Omnibus Law was too controversial for celebrities to risk their reputation. Anonymous buzzers were more effective for that task.

Abimanyu’s buzzer team was not the only one involved in the Omnibus Law campaign. Together with other coordinators, they prepared a social media strategy to ensure the contents would be widely discussed and grow into trending topics on Twitter. For such a big operation, cyber troops were mobilised at full capacity. ‘All troops were involved’, Abimanyu said, ‘So, influencers, buzzers – mid-level buzzers [pseudonym accounts with a small number of followers] with robots, too’. Robots, or ‘bots’, are semi-automated accounts operated through the TweetDeck application.

Those bots were programmed to tweet similar contents simultaneously at scheduled times and retweet the contents of the buzzers’ main accounts to increase reach. The main accounts were the anchors. ‘We can’t expect much from followers’, Abimanyu explained, referring to the limits of human engagements on social media posts. Bots are therefore needed to amplify the message and make the narrative dominate on social media. The personal touch of buzzers, in turn, creates the impression that the narrative comes from the netizen community. In this cycle of buzzing activity, the role of buzzers and bots is interconnected and complementary – and it requires an abundance of social media accounts.

Abimanyu’s team had its own content creators who designed the content: infographics, videos, images, memes and screenshot posts. ‘Every day, we have to make dozens [of] memes, videos and links – and we have to release right away’. New contents were often conceived in response to developing news stories and debates on social media. They also paid close attention to what and when other pro-Omnibus Law influencers and buzzer teams were posting so that their narrative would not clash and their content wouldn’t overlap. Sometimes, fellow influencers would race against each other when receiving specific instructions from ‘above’. ‘If Lesmana posts, I will post’, says Abimanyu, referring to another influencer. ‘If Lesmana is faster at it, it means his followers will retweet his posts, not mine’. For commercial influencers and big buzzers, numbers of followers and post engagements in the long term affect their market value and price rate. Competition was therefore high, further spurring buzzers’ fervour to sell the Omnibus Law.

A cyber crusade

Convincing the public of the benefits of the Omnibus Law was the first concern. One infographic, for example, was titled ‘Pak Jokowi Wants Investments to Have an Impact on the Entire Society’. It was spread far and wide on Twitter using the hashtag #OmnibusBeriManfaatBaik, ‘Omnibus [Law] brings good benefits’. Another infographic featured the headline, ‘The Job Creation Law Opens Three Million Jobs per Year’, with a photo of the minister of manpower. Other contents served to counter critics’ claims on the damaging effects of the Omnibus Law on the environment. One infographic featured a statement from the Secretary General of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, ‘We will defend to the utmost environmental sustainability in every business or investment in various fields’.

Besides highlighting the blessings of the Omnibus Law, cyber troops also engaged in a ‘negative’ campaign to discredit its critics. This part of the job was carried out by a team known as ‘negative buzzers’. Their task was, first, to delegitimise the demonstrators on the streets. From the start, government officials at the national and provincial levels argued that the demonstrators were misguided and uninformed, which put their understanding of the Omnibus Law in doubt. As several officials stated: ‘Did you actually read it?’, referring to the 1028-page manuscript of the Omnibus Law, which was revised multiple times and not easily accessible to the public. Buzzers simply amplified this message, mocking the protesters as naïve dupes.

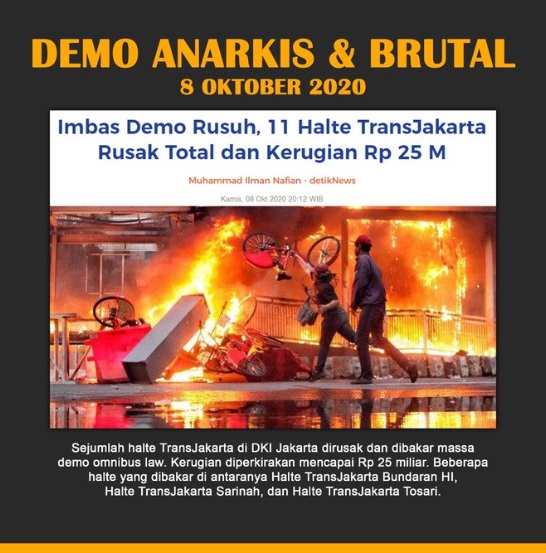

In addition, the demonstrators were portrayed as rioters. One visual, for example, showed a photo of a bus stop engulfed in flames beneath the headline ‘Effect of Riotous Demo: 11 TransJakarta Bus Stops Demolished, Loss of Rp 25 Billion’. Captioned ‘ANARCHIC & BRUTAL DEMO’, the buzzers quickly made the visual viral on Twitter. Another displayed a claim from the army that ‘100 thugs from outside Jakarta were promised money to demonstrate’. It was captioned, ‘PROVEN!!! ANARCHIC DEMO 8 OCTOBER FUNDED BY SPONSOR’. These visuals exemplified the typical format of negative buzzers: to magnify media coverage that creates a bad image of the demonstrations and embellish it into a spectacular story of hidden manipulators with a subversive agenda.

Negative buzzers also attacked activists directly. One tactic was to tarnish activists’ reputation by ‘exposing’ them as hypocrites. For example, a screenshot was circulated of a tweet in which an activist – known for his frequent agitations against the Omnibus Law on social media – appeared to endorse a new product. Buzzers stamped the image with the text ‘Capitalist Buzzer’, thus reversing the label to imply that it turns out that activists are also buzzers who serve the interests of capitalist investors.

Finally, a common tactic was to accuse activists of spreading ‘hoaxes’ – a criminal offence carrying a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison. The news of the crime was spread on Twitter, and numerous small buzzer accounts jumped on it. This tactic was often combined with doxing, or exposing private information about the activist being attacked. ‘Here is the bastard’, tweeted one account while doxing personal photos. Another account responded, ‘Just sentence him to death’.

Many activists were demoralised by these relentless digital attacks. Moreover, the negative atmosphere and chaos created by cyber troops in the digital public sphere led ordinary netizens to shy away from discussing the controversial Omnibus Law. Open support for the protest rapidly dwindled, leaving only the buzzers’ hashtags trending on Twitter.

Democracy in decline

The success of cyber troops during the Omnibus Law controversy signals a crisis of declining democratic values in Indonesia. It highlights the threat towards civic space and democratic accountability when government policy and communications lack transparency. As filmmaker and anti-Omnibus Law activist Dhandy Laksono said, the government should communicate policy ideas like the Omnibus Law in a transparent manner, allow public access to the data and then facilitate public feedback. ‘But what happens is, the data cannot be accessed, the buzzers are unleashed, and all this is pushed through in a time of pandemic, too’, he said. Dhandy is rather pessimistic: ‘Buzzers will always be there, for sure’, he says. ‘The government uses them because they are effective.’

The Omnibus Law case indicates not only government consolidation but also an oligarchic consolidation formed between the government and business. The Omnibus Law task force was predominantly composed of big businessmen from the Indonesian chamber of commerce (including a conglomerate who owns Italian football club Inter Milan). The parliament, which predominantly supported the Omnibus Law legislation, is also mostly (55 per cent) composed of businessmen. This turned out to have a major impact on the financing of cyber troop operations in Indonesia, in particular during the Omnibus Law campaign. Cyber troops were deployed in full force to sell the illusion of economic growth, which activists believed was actually just the oligarchy’s game to exploit resources armed with formal legal mechanisms. People like Abimanyu earn a decent income from this game of illusions; are they the foot soldiers of big capital?

Lailuddin Mufti (lailuddin@gmail.com) has expertise in public policy and public affairs. He holds a BA in Political Science from Universitas Indonesia and currently works as a policy analyst. Pradipa P. Rasidi (pp.rasidi@gmail.com) is an aspiring digital anthropologist and occasional web developer, studying cyborg politics and rumour/conspiracy theories. He has an MA in Anthropology from Universitas Indonesia, and currently works as a research assistant.