Pradipa P. Rasidi & Wijayanto

Aldi’s thumbs made an urgent ticking sound as he tapped the screen of his Xiaomi smartphone. He was fully engrossed in his phone, unresponsive to anything around him. After a few minutes he put the Xiaomi down, but immediately grabbed another smartphone. He took a deep breath, his eyes fixed on the new phone, his fingers rapidly typing. At that moment, Aldi, a man in his thirties, was working on three ‘buzzing’ projects simultaneously. He was used to it; he often took on several projects when there were ‘many orders’ – especially during the pandemic. He was not the only buzzer who was flooded with projects. According to the manager of one buzzer enterprise, the demand for their services increased up to 500 per cent during the pandemic.

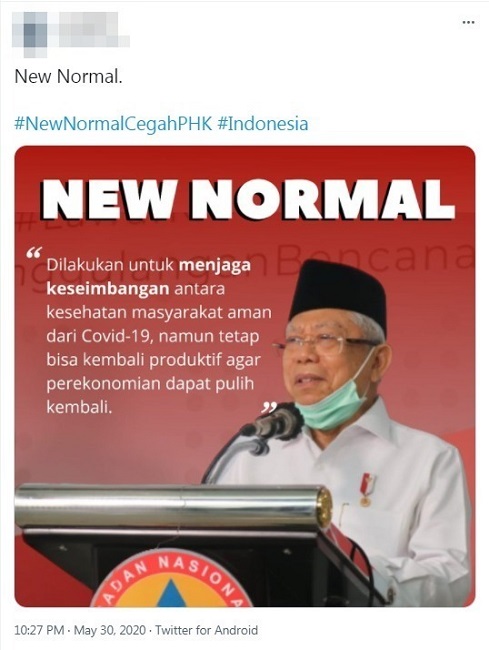

The COVID-19 pandemic amplified the role of digital platforms in the everyday lives of urban citizens. Forced to stay at home for most of the time, their social and economic activities were more than ever mediated by digital communications. Political and government agents, too, made extensive use of online platforms and social media became a vital medium for conveying political messages. Accordingly, the demand for political buzzers rose sharply. The ‘many orders’ they received in this period largely revolved around the central government’s need to promote its ‘New Normal’ policy. Promptly, buzzers like Aldi embarked on a virtual guerrilla campaign, entering private homes through people’s smartphones and computer screens in order to draw them back into the outside world.

The New Normal campaign was not just a lucrative business for buzzers, it also marked a new direction in buzzer operations. Previously, political buzzers were mainly deployed in tight-knit teams during (and after) elections. Now, they work side-by-side with brand influencers and may be contracted to work with people they never physically meet, proving themselves to be instrumental for promoting government policy to the citizenry at large.

Pandemic politics

The New Normal policy was President Joko Widodo’s (Jokowi’s) attempt to compel citizens to carry on their normal activities during the pandemic, albeit while following the health protocols of wearing face masks, washing hands frequently, avoiding crowds and populating work places at half capacity. The policy reflected Jokowi’s concern about the stagnating economy due to the pandemic. ‘This virus won’t disappear. Therefore, we have to live side by side with COVID’, said the president. ‘We want to stay productive, but safe from COVID. That’s what we want.’

But the New Normal policy was strongly criticised. Critics decried the government’s prioritising of the economy over public health, and generally its negligent response to the pandemic. At the start of the pandemic, for instance, Jokowi reportedly allocated Rp.72 billion (almost A$7 million) to promote (foreign) tourism, including subsidised flight ticket discounts and funds for ‘influencer and media relations’. Before COVID-19 was first detected in Indonesia on 2 March 2020, and even thereafter, then Health Minister Terawan Agus Putranto denied the dangers of the virus, claiming it could be warded off by prayer and, in the unlikely case of infection, the disease could easily be cured by positive thinking. Vice-president Ma’ruf Amin similarly recommended prayer while other ministers of state downplayed the virus with jokes. Such responses prompted fierce objections from scientists, health workers and civil society activists.

Opposition parties, particularly the Democratic Party, also joined the criticism. But they were driven not just by public health concerns. Recognising a political opportunity in the central government’s failing response to the pandemic, these parties pushed for a lockdown. By the end of March 2020, Jokowi saw himself forced to allow provincial governments to implement a form of lockdown in their region, called large-scale social restrictions (Pembatasan Sosial Berskala Besar or PSBB). Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan, Jokowi’s political rival, was the first to put PSBB into effect. Anies Baswedan’s proactive pandemic response has since been used by opposition parties to promote his candidacy for the 2024 presidential election. The pandemic response thus became a political issue.

But Jokowi was unmoved by the political challenge. State institutions, including the ministries of economics, health and tourism, swiftly joined the New Normal campaign, allocating considerable resources. ‘Instructions from above’, said one ministry official. Part of those resources were used to mobilise cyber troops, both influencers and buzzers. Although the New Normal policy was declared only on 7 May 2020, the cyber troops were put to work as early as March 2020.

Re-manufacturing consent

Many citizens feared that the pandemic in Indonesia was spiralling out of control. Stories abounded on social media about COVID-19 victims being left to die without proper care. This raised doubts about the official death figures – could it be worse than reported? As calls for a lockdown thus grew louder, the cyber troops jumped into action, filling social media with Jokowi’s economic argument – a lockdown will put citizens’ livelihoods at risk.

‘Some of my friends, day-labourers, have already been dismissed because there’s word of a lockdown in their town’, so one buzzer tweeted. ‘If it’s going to be like this, who can they turn to for food?’ One influencer similarly wrote ‘There are 13 million workers in the tourism sector. If this sector isn’t immediately opened using the New Normal concept, imagine what will happen if even just half of them have to be fired’. Additionally, cyber troops spread positive news stories and figures of recovered COVID-19 patients to counter doubts about the official figures. Their message – COVID-19 is not that deadly; therefore, businesses can resume their activities as normal, as long as people follow the basic health protocol. In contrast, figures on the death toll remained sensitive and were better avoided. One influencer recalled being scolded by a ministry official for citing a high number of deaths.

Cyber troops were also tasked with explaining the procedures and benefits of the New Normal. They did so by spreading videos, infographics and memes on Twitter, Instagram and in WhatsApp groups, consistently tagging their posts with one or more of the following hashtags: #TataKehidupanBaru (new life order), #DisiplinPolaHidupBaru (discipline is the new life pattern), #DisiplinKunciNewNormal (‘discipline is the key to the New Normal), #BersamaJagaIndonesia (protecting Indonesia together), #NewNormalCegahPHK (New Normal prevents lay-offs) and #NewNormalPulihkanEkonomi (New Normal recovers the economy). The consistent use of these hashtags ensured uniformity of the message. Furthermore, it tied the argument of economic welfare to the mantra of discipline in observing health protocols, which together created the narrative of a ‘new life order’ – a safe and prosperous order.

Cyber troops were not alone in spreading the message. Mainstream media and the police also supported the campaign. Our social network analysis, conducted in the second half of May 2020, shows that mainstream news coverage on the New Normal policy predominantly supported Jokowi’s position on the need to bolster the economy during the pandemic. The same narrative filled the social media accounts of the police. Mainstream media, the police and cyber troops thus jointly manufactured the public’s consent.

Cyber troops, however, had the additional task of punishing, and thus discouraging, dissent. Critics of the New Normal were harshly attacked. Prominent activists were their main target because, compared to political rivals such as Anies Baswedan, activists were considered the bigger threat. As one buzzer explained, activists ‘have their own kind of influence’ because they are not involved in the elite’s political rivalries. Thus, cyber troops were engaged to systematically discredit activists that criticised the New Normal policy. Not all cyber troops were involved in this task – only small teams of ‘negative buzzers’ were assigned for concerted attacks. One tactic was to consistently frame activists and other critics as ‘SJW’ or social justice warriors – a label adopted from netizen slurs portraying activists as self-righteous hypocrites whose only job was to spread unfounded accusations while pocketing cash from foreign funders. As well as activists, media that reported critically on the New Normal policy also felt the heat. For example, news magazine, Tempo, was labelled ‘SJW media’ and accused of fabricating stories to attract funding.

Another common tactic was to intimidate or embarrass activists through ‘doxing’, the practice of publishing private or personal information about an individual or organisation online. Some buzzer operations included a special ‘research team’ to track down activists’ digital traces and personal information, which were then forwarded to ‘negative’ buzzer and influencer teams to be exposed on social media. Aldi was part of one such team tasked with ‘beating up’ critics. Aldi, who is a former student activist, felt conflicted about this part of the job. ‘Because some of my friends are activists, you know’, he said. Aldi actually disagrees with the tactic of doxing but feels there is nothing he can do about it since doxing has become part and parcel of the ‘modus operandi’ of not only the government’s cyber troops but also the opposition parties that similarly attacked them.

A multi-actor project

The New Normal campaign involved many actors and institutions. The cyber troops involved were therefore also heterogeneous. Some were former members of the volunteer teams that championed Jokowi in the 2012 gubernatorial election in Jakarta and the presidential elections in 2014 and 2019. Others were enrolled by the ministries involved in the New Normal campaign. These also included commercial influencers and bloggers, who were recruited through advertisement companies or acquaintances in the government. They were all coordinated in different ways, operating in different structures.

Aldi was part of the network of the former volunteer teams. Their job was to promote all of Jokowi’s policies, including the New Normal. In a special WhatsApp group, their coordinator would send the contents to be spread on social media. According to Aldi, cyber troop operations for the New Normal were financed from the private funds of the Minister of State Owned Enterprises, Erick Thohir, not from the central government. But this is disputed by one of Aldi’s colleagues, who claims the money came from special ‘socialisation funds’ of the Committee for Handling COVID-19 and National Economic Recovery. This committee’s chief executive is Erick Thohir. Regardless of the source, Aldi has an (unwritten) contract that earns him Rp.3.000.000 per month. But he says it is not for the money that he defends ‘Jokowi’s interests’ – he could earn a higher income from commercial projects. Aldi believes that at present President Jokowi is still the right person to lead Indonesia.

In contrast, Yara is a commercial influencer without ties to Jokowi, who usually promotes products and business services. Campaigning for government policy was only a side job. She was recruited through an acquaintance who is involved in a group working closely with the health ministry. ‘Government jobs are easy money!’, Yara said. ‘Really easy money because the topic is never complicated’. In contrast to her other promotion jobs, in which her clients closely monitor her work, she feels government projects allow her more creative freedom. Yara was paid per task by the ministry, ‘about 100 to 150 thousand [rupiah]’. All she had to do was create a tweet thread to promote the health protocol. She worked in an occasional team of about 25 other influencers, who were coordinated in a WhatsApp group for just that task. The coordinator would only check if each influencer had completed the task – the style and content of the message was up to each individual influencer.

For Yara, the New Normal campaign suited her interest in health topics. Moreover, it helped to increase her followers on her social media accounts and blog. In those early months of the pandemic, she recalled, anything related to COVID equalled ‘traffic’ on social media; that is what attracted her. She came to regret her involvement, however, once the pandemic in Indonesia turned for the worse. ‘I didn’t expect the situation to be spiralling down like this…’ she said.

Normalising cyber troops

Despite the worsening of the pandemic, the central government keeps insisting that society needs to go on as normal. The strategy seems to be working. Growing impatient with the pandemic’s disruption of their everyday lives, ever more citizens join the ‘going back to business’ chorus. Netizens happily welcomed the reopening of malls, gyms and cinemas in August 2020, echoing the message that this saves employees’ livelihoods. Cyber troops played an important role in manufacturing this new public consensus.

In turn, the New Normal campaign has normalised the use of cyber troops for government communications. Some government agents had used cyber troops before, but the scale of the New Normal operation and the number of actors and institutions involved indicates that cyber troops became an accepted part of the outsourcing strategy of government communications. As one ministry official justified it, ‘If it’s us talking, we just sound like merchants selling their own wares, therefore it was more effective to sell the message ‘from others’ angles’. Instead of the government speaking in its own capacity, they used the outsourced forces of cyber troops to make it seem as if the message represents public sentiment. This hurts not only the public, who deserve accountability from the government, but also the cyber troops who act as scapegoats if things turn sour.

The cyber troops themselves, however, are optimistic. Aldi is certain that cyber troops are the future of digital communications. With his seven years of buzzer experience, he predicts buzzers will soon function like bodyguards – protecting public figures by unconventional means. ‘Sooner or later they all need buzzers’, he said, ‘all politicians will have them … that’s a fact!’ Aldi grinned at the prospect. Indeed, cyber troops are undeniably part of digital transformation. But when asked what this means for those who cannot afford their own cyber troops – such as the general public – Aldi did not respond but his grin turned into a frown.

Pradipa P Rasidi (pp.rasidi@gmail.com) is an aspiring digital anthropologist and occasional web developer, studying cyborg politics and rumour/conspiracy theories. He has an MA in Anthropology from the University of Indonesia, and currently works as a research assistant. Wijayanto (wijayanto@live.undip.ac.id) is director of the LP3ES Center for Media and Democracy and lecturer in Government Science, Diponegoro University.