Ali Nur Alizen & Maarif Setiadi Fajar

In the run-up to the 2019 presidential election Sengkuni (not his real name) received daily emails from Joko Widodo’s (‘Jokowi’s’) campaign team. They sent him pictures of Jokowi’s visits, overviews of his achievements while in office, details of his daily schedule and statistics about Indonesia’s development. It was Sengkuni’s job to turn those materials into captioned infographics and memes, to be posted by the many social media ‘buzzers’ working below him. Personally, Sengkuni is not really interested in politics and he didn’t care who would win the elections – but he appreciated the money that this work brought in. ‘It is not bad’, he said, ‘I was given Rp4 million a month, and in the week before the candidate debates and election day, I could make double that amount’.

Radjiman, on the other hand, joined Jokowi’s campaign team as a volunteer because he wanted Jokowi to win the election. Owing to his computer skills he was quickly recruited to support the online campaign. It brought him many adventures – he followed Jokowi throughout Indonesia on the campaign trail – and made a solid income. ‘I earned enough to live from, and more than in my previous job.’ Radjiman was a coordinator of Jokowi’s digital campaign team. It was his job to control the number of tweets the buzzers would send out, decide which hashtags would be used, determine whether a positive or negative tone should be struck, and what content should be used.

Both Sengkuni and Radjiman were members of the large ‘digital success teams’ that both Jokowi and his rival Prabowo Subianto, relied on during the 2019 presidential election. While the use of social media in electoral campaigns is not uncommon, this time around both campaigns also employed secretive teams of buzzers to shape and manipulate public perceptions. In previous elections the boundaries between digital campaigning and public opinion manipulation had already begun to blur. But during the 2019 elections cyber troop operations intensified and have now become an intrinsic part of Indonesian electoral politics.

The rise of cyber troops

The use of social media in elections can be traced back to the 2012 gubernatorial election in Jakarta, in which Jokowi – formerly mayor of Solo and still a relative political outsider – defeated the incumbent Fauzi Bowo. His victory was partly due to an energetic social media campaign driven by digitally-savvy volunteers. In the 2014 presidential election those volunteers again used social media to rally support for Jokowi against his opponent, Prabowo Subianto. The campaign teams of both candidates made use of influencers and unregistered teams of buzzers. This marked the rise of organised cyber troops in Indonesian electoral campaigning.

The role and impact of buzzers became more prominent in the run-up to the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election, in which Anies Baswedan defeated the incumbent Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (known as ‘Ahok’). Ahok’s defeat was largely the result of a concerted online as well as offline effort to frame him for blasphemy, based on a manipulated video of one of his speeches, in which Ahok – a Christian with ethnic Chinese roots – referenced a verse from the Quran. The edited video went viral on social media and prompted a series of massive demonstrations by Islamic hardliners, as well as a fierce ‘digital jihad’ by a cyber troop collective called the Muslim Cyber Army (MCA). This paved the way for Ahok’s prosecution and subsequent sentencing to two years in prison on a charge of blasphemy.

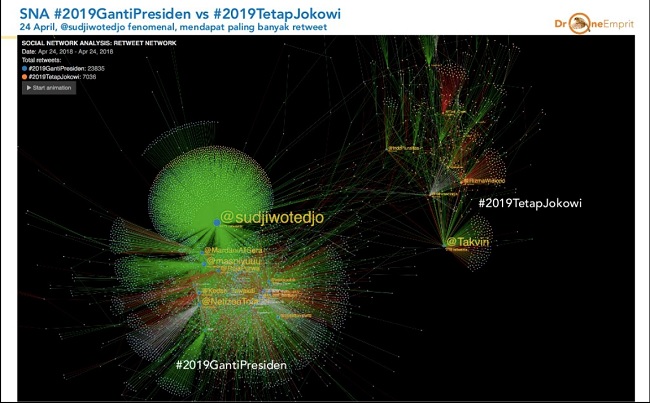

Ahok’s downfall made the Jokowi camp acutely aware of their vulnerability to the use of so-called ‘identity politics’ by their opponents – in particular, the exploitation of Islamic sentiments to rally the majority Muslim population against the president. In April 2018, one year before the 2019 election, Islamic opposition parties launched an online campaign against Jokowi, using the hashtag #2019GantiPresiden, ‘Change the President in 2019’. This hashtag campaign became a popular trend on Twitter and other social media platforms throughout the year, driven by MCA and other cyber troops. In the following months, Jokowi took on a more pious image and chose the Islamic cleric Ma'ruf Amin – then chair of the Indonesian Ulema Council and leader of Nahdlatul Ulama, Indonesia’s largest Islamic organisation – as his running mate. In addition, the Jokowi camp shored up their digital campaign, using not only social media experts that were formally part of the electoral ‘success team’, but also mobilising influencers and cyber troops not formally linked to the campaign. So did the Prabowo camp.

#2019GantiPresiden: attacking Jokowi

One of the politicians behind the #2019GantiPresiden (‘change the president in 2019’) campaign was Bhisma (not his real name). In our interview with him, he claimed that this hashtag campaign was a ‘constitutional movement’ (gerakan yang konstitusional), because ‘to change the president every five years is a political aspiration that is enshrined in the Constitution’. According to Bhisma, ‘there is nothing wrong with that hashtag to change the president – what’s wrong is that those who support the sitting president then get annoyed with that hashtag’. Bhisma claimed there was no premeditated plan to make the hashtag go viral on social media. He explained that in a polarised political situation, opponents of the president naturally rallied behind this hashtag. All the more ‘because it’s clear that the mainstream media all support Jokowi, while those on social media generally want to change the president’. The hashtag became a ‘uniting force’ for the opposition, he said, which is why ‘the Jokowi regime was so afraid of it’. Because of this fear, offline rallies of the #2019GantiPresiden movement in the regions would often be repressed. ‘If Jokowi wasn’t backed by the armed forces, he would have lost.’

Bhisma insisted that the hashtag campaign was a spontaneous movement that did not involve paid buzzer armies. ‘Paid buzzers work in a structured and organised manner’, he argued, ‘the Muslim Cyber Army clearly did not, they were really self-motivated, that’s the difference between those who get paid and those who do not’. He claimed the campaign was purely funded from the sales of merchandise such as T-shirts printed with the #2019GantiPresiden logo. However, according to one of the coordinators of the campaign, Gareng (not his real name), ‘It’s too simple to claim that the 2019 campaign only relied on T-shirts’. An experienced buzzer himself, Gareng supervised buzzer teams involved in this online campaign. He told us it was funded by legislators supporting Prabowo and his running mate, Sandiaga Uno, as well as some businessmen: ‘The source of financing came from the Prabowo-Sandi coalition: candidates and businessmen who for pragmatic and idealistic reasons support the number 2 couple’, he said, referring to the duo’s ballot number.

The modus operandi of the #2019GantiPresiden campaign also suggests higher levels of organisation. As Gareng explained, their buzzer teams had to carry out a concerted strategy of disseminating specific narratives meant to discredit Jokowi. Although Gareng insisted that that he would never engage in ‘black campaigns’, he helped to create several successful online campaigns that tainted Jokowi. His team tried to associate Jokowi with the defunct Indonesian Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia: PKI). They published posts claiming that Jokowi’s campaign slogan of ‘Mental Revolution’ was actually an old PKI slogan, and highlighted Jokowi’s relationship with (communist) China.

One of the frontline buzzers in Prabowo’s electoral campaign and the #2019GantiPresiden movement was Jatayu (not his real name). He explained that cyber troop operations had started long before the 2019 elections. One of the methods used was to conduct fake online polls, in which the results were manufactured so as to create the impression that Jokowi’s opponents were very popular. ‘For example, suppose there is a poll’, Jatayu explained, ‘We poll candidates one, two, three and four. Now, if we want to make the public believe that [one of these candidates] has high electability in the eyes of the public, we will fabricate a polling process’. This fake polling was followed by efforts to boost online media coverage of the manipulated poll results – the contents of which were also created by the cyber troops – in order to encourage ordinary netizens to share the news.

#2019TetapJokowi: branding Jokowi

According to our informants Jokowi’s camp used the same tactics. One of the buzzers we interviewed, Gedun (not his real name) was originally a Prabowo supporter, but ahead of the 2019 election he was invited to join Jokowi’s national campaign team. Since then he has been one of Jokowi’s paid cyber troopers. While initially lured by the money, Gedun said that his involvement in the Jokowi campaign shook his confidence in Prabowo.

For the election campaign Jokowi’s social media campaign was run by four coordinators, who together managed 150 buzzers. This digital campaign team was housed in a high-end office building in Central Jakarta, which had been turned into a media centre with televisions mounted on the walls and 50 cubicles with computers. The team worked in shifts, around the clock: the morning group worked from 9am to 3pm, the evening team worked from 3pm until midnight and the night team worked from midnight to 9am.

There was a clear division of labour. First, the research team – taking up input from their team leader – identified possible topics and potential hashtags while collecting useful material. Then, the ‘production group’ or content creators, used that material to prepare the actual social media posts. Groups of buzzers then set about disseminating the posts using about 1000 fake social media accounts. They also solicited help from outside the team: the team leader would often ask (and pay) influencers – well-known individuals with many followers – to help spread particular posts. All these posts revolved around the central hashtag #2019TetapJokowi, ‘2019 Still Jokowi’, and were meant to raise the ‘brand value’ of the sitting president.

At the start of each shift the team leader chaired a meeting where he gave instructions about the topic that needed to ‘trend’ on social media that day. The team leader decided how many times the topic should be raised, and also provided an overview of the work pattern for the following day to ensure continuity in the content they were pushing out. Usually, across one shift, the target was to raise one to three trending topics.

The ‘buzzers’ were each provided with at least one ‘boat account’. These are accounts with 5000 followers or more. In addition, the buzzers created their own accounts which they tried to ‘grow’ by attracting followers. In one shift, each buzzer was expected to tweet from 50 to over 100 tweets per account in order to raise a trending topic. Thus, one buzzer could generate a minimum of 25,000 tweets in one shift. The night shift was not expected to tweet so much: not only is there much less ‘traffic’ during the night, there are less attacks from the opponents to respond to.

Team leader Radjiman acted on instructions from senior campaign leaders such as Kang Dede Budhiarto. But he also enjoyed considerable freedom to implement his own strategy. After participating in a course of training in social media campaign strategy at Gadjah Mada University, Radjiman explained that he shifted his preference to light-hearted and optimistic social media campaigns. Radjiman also started to train his own campaign teams in other parts of Indonesia. Radjiman’s aim for his teams of buzzers, was to create as big a volume of tweets as possible. As Sengkuni explained, ‘we tried to keep the narrative simple, in order to make it pleasant and make each new Jokowi supporter feel welcome’. In that spirit Radjiman’s team avoided mentioning Jokowi’s opponent. ‘As much as possible we should never mention Prabowo's name in our narrative, whether good or bad’, Sengkuni said, ‘because that would raise Prabowo’s name. So, we focused on mentioning Jokowi’s name from each of our tweets’. To make their social activity appear natural, Sengkuni added, they made sure to interact with each other’s accounts.

For example, when Jokowi visited Padang on the campaign trail, the narrative that dominated on Twitter was the uniqueness and beauty of the region and its people. Another frequently chosen topic was the support of prominent people for Jokowi. One occasion that was magnified on social media was when the alumni association of the University of Indonesia (UI Alumni) expressed their support for Jokowi during one of Jokowi’s rallies at the Bung Karno Stadium in Jakarta, in January 2019. Promptly, Twitter was flooded with the hashtags #AlumniUIDukungJokowi (‘UI Alumni Support Jokowi’) and #AlumniUI4JKW (‘UI Alumni for Jokowi’).

For Sengkuni, ‘the most successful hashtags in the big campaign, were those [we launched] during the white concert before voting day’. The United White Concert was held at the Bung Karno Stadium on 13 April, to conclude Jokowi’s national campaign. With its star-studded line-up of famous musicians, artists, religious leaders and politicians, the social media posts about this event easily went viral. With a series of pre-planned hashtags such as #KonserPutihBerSATU (‘United White Concert’, with ‘satu’ or ‘one’ in the word ‘united’ capitalised to indicate Jokowi’s ballot number), #BarengJokowi (‘together with Jokowi’), and #KonserPutihAdalahKita (‘the white concert is us’) Sengkuni and his team members generated a lot of attention across multiple social media platforms. Moreover, Sengkuni recalled, the campaign ‘was supported by all the influencers simultaneously, bro. Wow, this broke the records. The topic became trending in no time’. This further helped to raise the event’s prominence in the mainstream media, which in turn prompted a mass volume of Twitter conversations on the topic by ordinary netizens.

During the 2019 election, an unknown number of buzzers affiliated to both Jokowi’s and Prabowo’s campaign were mobilised to flood social media with campaign messages. The actual influence of these cyber troops on voter behaviour is difficult to ascertain, but it is likely that the narratives they pushed on social media impacted on voters’ perceptions of the candidates. Whether motivated by idealism and conviction (like Radjiman), or merely by money (like Sengkuni), these armies of buzzers are now an important feature of election campaigns in Indonesia.

Ali Nur Alizen (alinuralizen12@gmail.com) and Maarif Setiadi Fajar are associate researchers at LP3ES, Jakarta.